the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Paleontology-themed comics and graphic novels, their potential for scientific outreach, and the bilingual graphic novel EUROPASAURUS – Life on Jurassic Islands

Jan Fischer

Joschua Knüppe

Henning Ahlers

Sebastian Körnig

Arila-Maria Perl

The first part of this article gives an overview of influential comics and graphic novels on paleontological themes from the last 12 decades. Through different forms of representation and narration, both clichés and the latest findings from paleontological research are presented in comics in an entertaining way for a broad audience. As a result, comics are often chroniclers of 20th century scientific history and contemporary paleoart.

The second part of this article deals with the development of the bilingual graphic novel EUROPASAURUS – Life on Jurassic Islands, which communicates knowledge from universities and museums to the public. This non-verbal comic presents the results of a paleontological research project on a Late Jurassic terrestrial biota from northern Germany in both a scientifically accurate and an easily understandable way, based on the way of life of various organisms and their habitats. Insights into the creative process, the perception of the book by the public, and ideas on how to raise public awareness of such a project are discussed.

- Article

(30470 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(28952 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The communication of scientific research via contemporary and creative ways is becoming more and more important for research institutions. Paleontological topics are often met with special interest by the public, especially when it comes to vertebrate paleontology. From our experience, maximum attention is paid to dinosaur research, which often reaches an international distribution in the media, depending on the momentary situation on the global news market. However, all press releases and subsequent press articles share one disadvantage – their short-lived nature. After a maximum of several days, the reports are no longer present in the media and will be quickly forgotten. Hence, this type of knowledge transfer does not appear to be particularly sustainable.

Books, on the other hand, are long-lasting and can accompany us our whole lifetime. Unfortunately, text-heavy popular science books do not reach all groups in our society equally (i.e., children from socially disadvantaged backgrounds) due to partially higher barriers of accessibility. Easily accessible formats such as comics and graphic novels offer opportunities to transmit science into possibly more neglected parts of our society.

This paper, consisting of two parts, addresses this issue with an example from the field of paleontology. The first part provides an overview of the historical development of paleontology-themed comics and graphic novels, the influence of paleoart in this genre, and the potential of graphic novels in transmitting science into the public. The second part focuses on the dinosaur-related graphic novel EUROPASAURUS – Life on Jurassic Islands as an example. We explain our motivation for its creation, the production process, and our strategy for advertising it, with the goal of encouraging other scientists to explain their research results to the public in a similar fashion.

1.1 Paleontology within popular science books

Paleontological discoveries became known to a wider audience in the mid-19th century, due to public lectures, the first “dinomania” following the creation of the Crystal Palace life-sized reconstructions of dinosaurs (Manucci and Romano, 2022), and the new spectacular dinosaur finds from the United States. Since then, manifold books, articles, and even collecting cards presenting the results and summaries of contemporary knowledge have been published. In the beginning, these publications were primarily addressed to an adult and educated readership (e.g., Flammarion, 1886; Knipe, 1905; Andrews, 1926; Bölsche, 1931; Knight, 1935; Augusta, 1942), but by the 1950s younger readers were also reached by a wide range of age-appropriate and lavishly illustrated books (e.g., Scheele, 1958; Watson, 1960; D'Ami, 1973; Norman, 1985). Nowadays, such children books dominate the market of nonprofessional paleontological publications, often resulting in a marginalization of dinosaur topics as “kids stuff” in the view of the general public (Liston, 2010). However, there were always outstanding paleontological popular science books for adult and mixed audiences as well (e.g., Augusta and Burian, 1956; Spinar, 1972; Stout, 1981; Cox et al., 1988; Norman, 1988; Czerkas and Czerkas, 1990; Holtz, 2007). All these books share a relatively text-intensive style, although many of them qualify as so-called “coffee table books” with a variety of large-sized colorful illustrations. Unfortunately, the information contained on specific paleontological topics is often slightly outdated by the time of release. This is especially true in children's books, a market where it is often not seen as necessary by publishers to be up to date. New ideas and paradigms in paleontological research take years to reach a non-academic audience and even decades to determine the perception of the general public on that topic (Ross et al., 2013). However, communication on the latest paleontological knowledge can be realized most quickly and effectively by a medium specifically aimed at a predominantly young audience (Liston, 2010) – the comic strip.

1.2 Influential paleoart

Paleoart is an art genre that depicts paleontological subjects realistically or artistically, reconstructing extinct biota and their habitats based on scientific data. Artists who strive to reconstruct prehistoric organisms and/or habitats as accurately as possible, often in close collaboration with paleontologists and other specialists (Germann, 1943), are so-called paleoartists (Hallett, 1987; Janzen, 2020). Although existing for about 200 years (Lescaze, 2017), paleoart still struggles for its reputation to be regarded as real art compared to the classic genres (Janzen, 2020). In recent decades, there have been many approaches to appreciating, classifying, and assessing paleoart and paleoartists (e.g., Czerkas and Olsen, 1987; Lescaze, 2017; Hübner, 2020; Janzen, 2020; Manucci and Romano, 2022), even including instructions for making one's own attempts (Witton, 2018). Paleoart is a crucial link between paleontology and public awareness because paleoartists illustrate paleontological theories in their life restorations (Murray, 1997; Spindler, 2020).

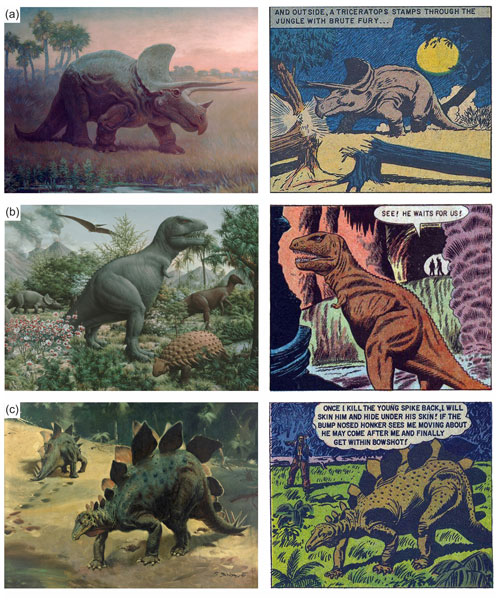

Figure 1Themes of great paleoartists and their mirror images in comics. (a) Charles R. Knight's classic Triceratops from 1928 (© Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago) and its comic counterpart in Turok, Son of Stone no. 10, December–February 1957–1958. (b) Rudolph Zallinger's iconic Tyrannosaurus from the 1947 mural The Age of Reptiles (©Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven) and its comic counterpart in Turok, Son of Stone no. 3, March–May 1956. (c) Zdeněk Burian's famous Stegosaurus from 1941 (© Charles University, Faculty of Science, Prague) and its comic counterpart in Turok, Son of Stone no. 16, June–August 1959 (Turok, Son of Stone™ & © Penguin Random House, Inc. Under license to Classic Media, LLC). All rights reserved.

Therefore, it is not surprising that contemporary paleoart has repeatedly served as a template for the depiction of prehistoric life in comics since the early 20th century. Without any paleontological research of their own, most comic authors and illustrators relied directly on preexisting visual ideas of the subject. Although often exaggerated in their presentation, the original artwork can often still be recognized in the animal contours, body postures, and sometimes even color patterns (Fig. 1). Many panel drawings were almost exact copies of their academic originals, which were recycled again and again. However, subsequent strips also independently aligned themselves with the prevailing scientific view and reconstruction (Murray, 1993; Liston, 2010). This transformation of contemporary paleoart and its underlying paleontological ideas into panels makes comics chroniclers of advances in paleontology. Many dinosaur comics thus accurately reflect contemporary paleoart and the paleontological paradigms of the time. In particular, the paleoart of the so-called “Classic Era” from 1890 to the late 1960s (Witton, 2018) generated manifold inspiration and direct templates for comics. During this period a triumvirate of paleoartists, the preeminent authorities in the field, provided the graphical fuel for memorable prehistoric worlds and impressive archaic antagonists. Their paleoart was responsible for establishing the standards of what dinosaurs should look like at the time, inspiring generations for how dinosaurs were to be portrayed. They were so widespread and well-known in cultural memory through books, comics, and movies that even today many people are familiar with their work (Gould, 1993; Czerkas, 2006; Ross et al., 2013; Janzen, 2020), even though they may never have heard of their names.

The first of these most influential paleoartists was Charles Robert Knight (1874–1953). Knight was a classically trained artist who specialized in animal paintings. He is probably best known for his collaborative work on reconstructing extinct organisms with paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn at the American Museum of Natural History in New York (Paul, 1996). He also reconstructed many fossil taxa described by the rival paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. Knight almost single-handedly established the field of accurate artistic reconstruction of prehistoric life in public perception (Gould, 2001; Bissette, 2003) and can be regarded as the first internationally renowned paleoartist (Witton, 2020). Part of his legacy is his rigorous approach to reconstructing extinct animals, providing a guideline for subsequent generations (Knight, 1947). While his dinosaur reconstructions are outdated today, many of his paintings and drawings of mammals still hold up to modern standards. In two of the most famous and widely used templates of paleontological reconstructions, Knight established Brontosaurus as a semiaquatic behemoth and Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops as eternal enemies (Knight, 1935). In addition, his surprisingly dynamic Leaping Laelaps and numerous other murals and paintings reproduced in books, periodicals, and journals (e.g., Knight, 1935, 1942, 1946; Czerkas and Glut, 1982; Czerkas, 2006; Milner, 2012) provided a vast number of templates for prehistoric life forms in comics. For example, the lost worlds with wonders and threats of the early Tarzan and Turok series are unmissable testimonials to his work (Fig. 1a).

The second member of the triumvirate was Rudolph Zallinger (1919–1995). His contribution to paleoart still echoes through paleontological history. While in his last year at the Yale School of Fine Arts in 1942, he was offered to add “some kind of decoration” to a large wall of the dinosaur hall at the Yale Peabody Museum. After pencil sketches and a preliminary small-scale painting, or model, in egg tempera, Zallinger worked for 3.5 years on the 33.5 m long mural The Age of Reptiles, a grand narrative of life from the Devonian to the end of the Cretaceous. The mural was finished in 1947 (Volpe, 2007) but did not become famous until a few years later, when Life magazine reprinted the preproduction model as a foldable panorama (Life, 1953). With that, Zallinger's fresco-like depictions of prehistoric life became the gold standard for portraying dinosaurs for years to come. In 1949, Zallinger received the Pulitzer Prize for his mural. He later created more paleoart for other publications (e.g., Watson, 1960; Zallinger, 1966), but his most influential work remains The Age of Reptiles. In particular, Zallinger's iconic Tyrannosaurus was frequently used in comic strips and serials until the 1960s (Fig. 1b). Entire stories, especially in Turok, were graphically based on this single image of a dinosaur in side view.

The third cornerstone for the inspiration (and plagiarism; Sadecký, 1982b) of prehistoric wildlife in countless comics was the Czech artist Zdeněk Burian (1905–1981), who may be the most influential paleoartist of the mid and late 20th century (Reich et al., 2021). His work shaped public perceptions of prehistoric life like no other (except Knight, depending on the European or American perspective). Burian achieved this by his immense productivity (with some 1300 images and preliminary sketches on prehistoric subjects; Rostislav Walica, personal communication, 2022) and through his appealing, highly detailed images. He began his career as an illustrator of adventure and science fiction novels (Sadecký, 1982a; Prokop, 2005). As such, he was not only a master of various media but also a skilled visual storyteller. Through his work on novels about mammoth hunters (Štorch, 1937), he came into contact with the paleontologist Josef Augusta and later with other scientists (Walica, 2003; Prokop, 2005). These fruitful collaborations resulted in several lavishly illustrated large-format books on evolution and the history of man (e.g., Augusta, 1942; Augusta and Burian, 1956, Spinar, 1972; Wolf, 1977). Despite the Iron Curtain, his works have been translated and exported worldwide since the 1950s. Producing countless paleoart originals over several decades (Müller and Walica, 2022), Burian can be considered the legitimate successor of Knight (Witton, 2020). In comics, his first worldwide book success (Prehistoric Animals from 1956) can be traced precisely to Turok no. 11 in 1958, where copies of his depictions of prehistoric life started to complement and increasingly replace Knight and Zallinger's templates (Fig. 1c).

1.3 Comics and graphic novels about prehistoric life

Comics are a medium that expresses ideas with images. They often consist of sequences of panels of images and are frequently combined with text or other visual information. Graphic novels are books made up of comic content. They tell a longer and sometimes more complex story and are distinct from comic books that consist of comics, periodicals, and trade paperbacks. Moreover, they represent a successful marketing concept for a form of publication in which comics gain literary merit through book covers in order to be distributed by major publishers in bookstores (Abel and Klein, 2016). A discussion of prehistoric topics in cartoons is beyond the scope of this paper, although this theme and its sometimes even bidirectional influence on paleontology (e.g., Gary Larson's thagomizer; Holtz, 2007) would merit a review on its own.

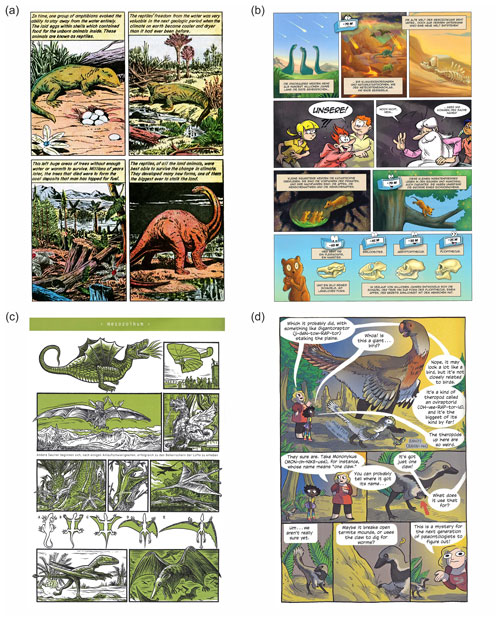

Like most other comics, strips involving prehistoric creatures are aimed predominately at a young target audience. The majority of previous and modern comics dealing with dinosaurs and other prehistoric life serve as pure entertainment. They represent the absolute majority of dinosaur comics with thousands of stories handling tales from science fiction, fantasy, horror, mystery, western, or the superhero genre (Glut, 1980). Only a small but diverse niche uses a different approach; not only providing enjoyable and thrilling stories but also contributing to the transfer of scientific knowledge and deepening the paleontological background beyond the entertainment factor. This type of subtle education of the audience may be achieved via individual panels with embedded information, via detailed elaborated scientific content in a comic book style, or via a format in between.

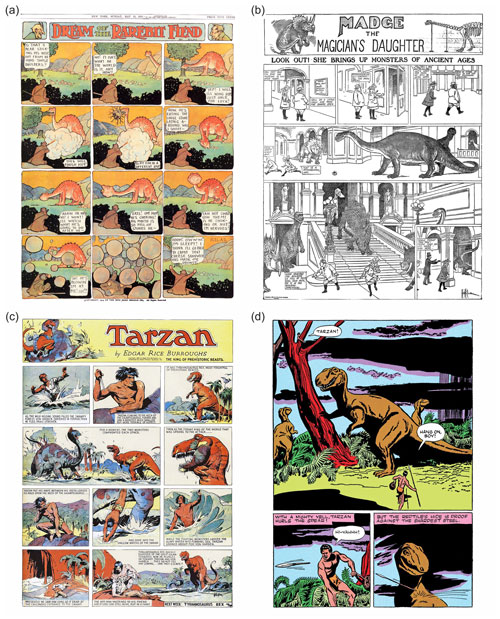

Figure 2Adventure stories 1. (a) A sauropod-like dinosaur in Windsor McCay's Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, 25 May 1913, which already displays behaviors of McCay's 1914 animated Gertie the Dinosaur (public domain). (b) The awakening of “Knightian” dinosaur incarnations in Madge the Magician's Daughter by William O. Wilson in 1907 (public domain). (c) The clash of Tarzan with a colorful Knightian Tyrannosaurus in Harold Foster's Edgar Rice Burrough's Tarzan, 23 October 1932 (© 1932, 2022 Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. Tarzan®, Edgar Rice Burroughs® Owned by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. and used by permission). (d) Several Knight-inspired predatory dinosaurs in Jesse Marsh's Tarzan comic no. 16, July–August 1950 (© 1950, 2017, 2022 Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. Tarzan®, Edgar Rice Burroughs® Owned by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. and used by permission.). All rights reserved.

Dinosaurs and their kin have always been a popular subject in comic strips. Starting as a recurring inventory of excitement or terror in Sunday newspaper edition stories, extinct animals later also got leading roles (sometimes as anthropomorphized characters) and even sequel stories (Glut, 1980; Murray, 1993; Bissette, 2003). They were used in several contexts, from entertainment to education, with a variety of formats in between. The strips grouped thematically below are a limited selection without any claim to completeness.

Adventure stories

The first and foremost use of prehistoric life in comics was – and still is – for the purpose of pure entertainment without any interest in paleontological education. Prehistoric animals are shown just as forces of nature. They are necessary to advance the story as villains (or heroes) or a MacGuffin (an object that is necessary to the plot but insignificant in itself), and they are merely used to create tension and action (Glut, 1980). The animals are usually depicted as dangerous, vicious, stupid, carnivorous, and often pose supernaturally large threats for the human protagonists. Commonly, the prehistoric life forms do not survive the encounter with humans. These strips are essentially not dinosaur comics but comics with dinosaurs (Bissette, 2003). Three recurring specific settings are widely used (Galle, 1993) to explain the presence of the prehistoric creatures: (1) lost-world areas, a realm where they survived until today; (2) other planets, strange worlds with primordial plants and animals; and (3) time travel, the journey into their time or their retrieval into modern times.

The earliest comic reference to dinosaurs is Prehistoric Peeps from 1893 (Merkl, 2015), in which prehistoric humans and dinosaurs satirically reflected and caricatured the present in anachronistic situations. A subsequent example of more prehistoric encounters is the classic Saturday newspaper comic strip Dream of a Rarebit Fiend by Windsor McCay, where dinosaurs repeatedly appeared between 1905 and 1913, and were remarkably accurately drawn by the standards of the time (Merkl, 2015). One of these comic pages (Fig. 2a) already foreshadowed a topic McCay later reworked in his well-known animated dinosaur film Gertie the Dinosaur in 1914 (Nathan and Crafton, 2013). Another classic newspaper strip, Madge, the Magician's Daughter, also used a diverse dinosaur menagerie already by 1907 (Fig. 2b) to show a museum trip from a surprising new side (Wilson, 2010). A more serious encounter was depicted in a multiple part Sunday edition of Edgar Rice Burrough's Tarzan by Harold Foster from 1932, where the protagonist met a carnivorous (!) sauropod, countless pterosaurs, and finally survived the attack of a giant and impressively colorful Tyrannosaurus rex (Fig. 2c; Carlin and Foster, 2013). It took another 5 years before the next comic dinosaur appeared. In 1937, Prince Valiant faced a sauropod-like swamp monster, which he defeated in the end. Tarzan's second encounter with a T. rex happened in 1945 in Burne Hogarth's strip, where Tarzan managed to impale the obtrusive carnivore (Hogarth, 2016). With no. 4 of the Tarzan comic in 1948, dinosaurs finally became a regular part of recurring Lost World stories for about 20 years, shaping many subsequent strips in their representational form and color scheme (Fig. 2d; DuBois and Thompson, 2017). Other comic serials started to use the potential of prehistoric threats and primordial adventures too, and prehistoric topics have flourished in countless issues ever since (Murray, 1993; Glut and Brett-Surman, 1997; Bissette, 2003). To date, nearly every superhero (team) in any franchise has had its own encounter with members of the Dinosauria or other prehistoric life forms (Glut, 1980). Starting in 1960 in Star-Spangled War Stories no. 90 by DC, US soldiers were repeatedly confronted with over-sized Mesozoic creatures on countless Pacific islands during World War II (Fig. 3a). It was not until 1968 that this War That Time Forgot ended after 45 explosive clashes in no. 137. In the German Piccolo comics from the 1950s such as Akim, Sohn des Dschungels (Akim, Son of the Jungle), Sigurd, der ritterliche Held (Sigurd, the Knightly Hero) or Raka, der Held des Jahres 2000 (Raka, Hero of the Year 2000), the protagonists experienced adventures with most stereotypical dinosaurs on a regular basis (ComicSelection, 2019). Even in the cataclysmic future world of Xenozoic Tales from 1987, also reprinted under the title Cadillacs and Dinosaurs, a variety of marvelously illustrated prehistoric animals, especially dinosaurs, complicated the postapocalyptic life of the two main characters for 14 issues (Fig. 3b; Schultz, 2013).

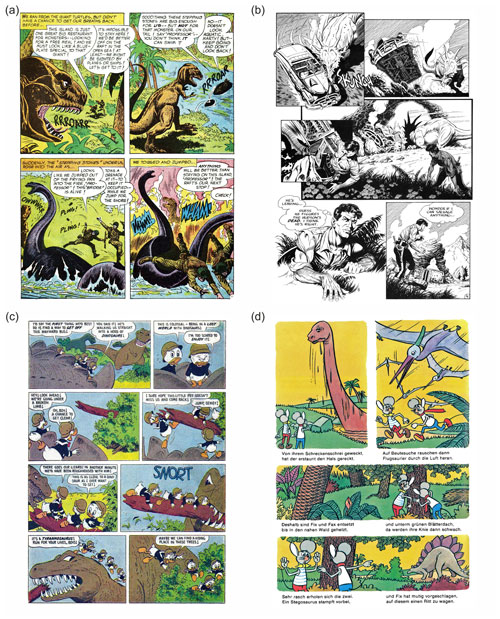

Figure 3Adventure stories 2. (a) The explosive clash between dinosaurs and American soldiers during WWII in Star-Spangled War Stories no. 96, May 1961 (©2022 DC Comics). (b) An inauspicious encounter between a Styracosaurus and protagonist Jack's Cadillac in the cataclysmic world of Mark Schultz Xenozoic Tales no. 9, September 1989 (Xenozoic™ & © 2022 Mark Schultz). (c) Forbidden Valley, Carl Barks' version of a lost world, that Donald and his nephews experience firsthand in Walt Disney's Donald Duck no. 54, July–August 1957 (© 2022 Disney). (d) The diverse prehistoric era in the 1974 time-travel adventure of Fix und Fax no. 193 (© Jürgen Kieser/2022 MOSAIK Steinchen für Steinchen Verlag). All rights reserved.

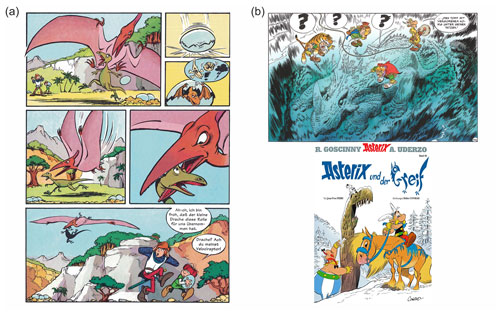

Figure 4Adventure stories 3. (a) The Abrafaxe experience rough manners in the Cretaceous in Mosaik no. 216, December 1993 (© 2022 MOSAIK – Die Abrafaxe). (b) In 50 BC, the Gauls and Romans, who are always at clinch, meet a frozen Burianesque Styracosaurus in Asterix no. 39, 2021 (ASTERIX® – OBELIX® – IDEFIX® & © 2022 LES EDITIONS ALBERT RENE, in the German-speaking area published by Egmont Ehapa Media). All rights reserved.

However, there are also peaceful encounters with the prehistoric menagerie in thematically quieter and more child-friendly comic series. In 1957, Donald Duck and his nephews unintentionally experienced a Forbidden Valley lost world adventure in Walt Disney's Donald Duck no. 54 (Fig. 3c). In 1974, German Fix und Fax (nos. 193–199) also visited a colorful prehistoric setting (inspired by drawings from Bölsche, 1931) without causing collateral damage among the inhabitants (Fig. 3d; Kieser, 2018). A similar story was told in a short episode for the protagonist trio Abrafaxe in Mosaik nos. 216–217, where they accidentally time traveled to the Cretaceous (Fig. 4a; Schleiter, 2011). In series such as The Adventures of Tintin (Hergé, 1947) and even Asterix (Fig. 4b; Ferri and Conrad, 2021), dinosaurs appeared as MacGuffins instead of antagonists. In Calvin and Hobbes, prehistoric worlds are regular retreats of fantasy from the dreariness of everyday life (Watterson, 2012).

Figure 5Adventure stories supported by educational information. (a) A classic Zallinger Tyrannosaurus attacks the two main characters in Turok, Son of Stone no. 10, December–February 1957–1958 (Turok, Son of Stone™ & © Penguin Random House, Inc. Under license to Classic Media, LLC). (b) A Young Earth paleo story without human characters supplements Turok, Son of Stone in no. 12, June–August 1958 (Turok, Son of Stone™ & © Penguin Random House, Inc. Under license to Classic Media, LLC). (c) On an alien planet, the Digedags find living 1950s dinosaurs in Mosaik by Hannes Hegen no. 62, January 1962 (© 2006 Tessloff Verlag). (d) Dinosaur as shadow plays in the memories of survivors of the Cretaceous apocalypse in Mike Keesey's Paleocene no. 1, 2020 (© 2022 Mike Keesey). All rights reserved.

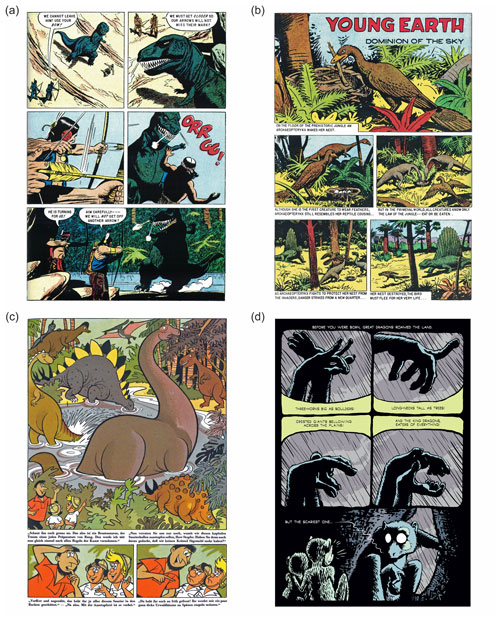

Adventure stories supported by educational information

Besides pure adventure stories with prehistoric inventories, more educational approaches have been realized too. The Dell serial Turok, Son of Stone also chose a lost world setting. Starting in 1954, it became the longest running dinosaur serial with altogether 131 issues until 1982. Two Native Americans, Turok and his young companion Andar, discover a lost valley full of largely varied, preferably dangerous ancient life forms. While all stories dealt with their unsuccessful attempts to leave this inhospitable place, they met (and killed) countless prehistoric creatures (Fig. 5a). In contrast to Tarzan, where the dinosaurs were only a means for entertainment, the Turok authors provided additional information about prehistoric life to the reader. Supplementary pages were included in every issue, detached from the Turok universe. As of 1956, text pages about specific animals with illustrations as headers were included – strongly reminiscent of chocolate trading cards from the first half of the 20th century (Bölsche, 1916). By 1957, the additional separate short strip Young Earth was established to alternate with the main story in every issue (Fig. 5b), focusing solely on the prehistoric animals and explaining aspects like animal behavior or evolutionary patterns. While most of these stories mixed Paleozoic and Mesozoic taxa indiscriminately, they can be seen as the vanguard of the true dinosaur comics of the future. Similar approaches of additional brief scientific background information were used in the Dell Movie Classics, such as no. 845 (The Land Unknown, 1957), no. 1120 (Dinosaurus!, 1960), and no. 1145 (The Lost World, 1960), to supplement the stories in the related films. Another example is the space storyline of the German Digedags in Mosaik between 1961 and 1962 (Hegen, 2004, 2006). For 10 issues, starting with no. 51, the protagonists investigated several planets with different stages of earth's evolution (even in the correct evolutionary order) (Fig. 5c), while the back cover in each issue summarized scientific facts. The same approach, although from another perspective, was used recently in Paleocene by Mike Keesey. Here, we see the world through the eyes of anthropomorphized lemur-like primates just a decade after the asteroid event that killed the dinosaurs, leaving behind a devastated world at the dawn of a new era. While the primates try to survive against avian dinosaurs, the non-avian dinosaurs still exist as dragons in fairy tales of the elders (Fig. 5d). Concise scientific facts introduce every issue and provide framework and context for the events.

Figure 6Adventure stories supported by sophisticated educational information. (a) Not everything was better in the past, as an excerpt from Cretaceous life in Jim Lawson's Paleo vividly shows (© 2016 Jim Lawson). (b) Even Tyrannosaurus did not always have it easy in Ted Rechlin's Tyrannosaurs rex (© 2016 Ted Rechlin). Self-narrative storyboards. (c) Textless telling of impressive-dynamic dinosaur stories in Ricardo Delgado's Age of Reptiles narrative Tribal Warfare, 1993 (Age of Reptiles™& © 2022 Ricardo Delgado). (d) A creative use of panels by Tadd Galusha in Cretaceous in 2019 to tell a textless story (Cretaceous™ & © 2019 Tadd Galusha). All rights reserved.

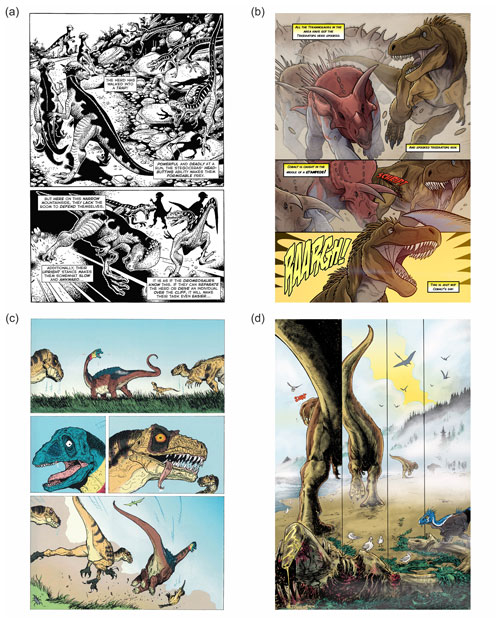

Adventure stories supported by sophisticated educational information

In tradition and as an extension of the Young Earth's narrative style, longer stories were produced with a scientifically more robust background and naturalistic depictions of the animals and environments. The focus in these modern comics was on the needs and experiences, but also failures, of the dinosaur protagonists. Paleo is an anthology of a dozen different dinosaur stories from the Late Cretaceous in detailed monochrome panels, highlighting also other animals such as marine reptiles and pterosaurs (Fig. 6a; Lawson, 2016). In contrast, Tyrannosaurus rex focused on a feathered tyrannosaurid individual, Cobald, and its daily struggle to survive and to find a mate in the Late Cretaceous (Fig. 6b; Rechlin, 2016). Subsequent volumes have extended this concept to other dinosaurs, as well as the evolution of sharks, whales, and Ice Age mammals (e.g., Rechlin, 2018, 2019).

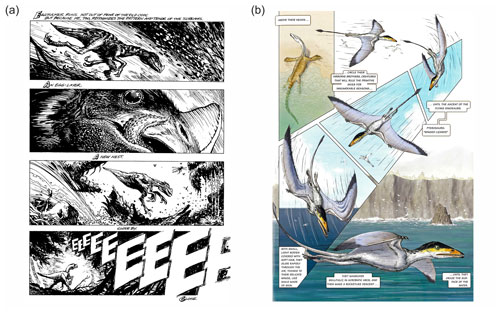

Self-narrative storyboards

Another approach is text-reduced visual storytelling, similar to a sophisticated storyboard. This comic format is used in Age of Reptiles by Dark Horse Comics (Delgado, 2011, 2015), which depicts the fate of several dinosaurs in four stories: Tribal Warfare from 1993 featured a conflict between a Tyrannosaurus family and a pack of Deinonychus, The Hunt from 1996 followed a vendetta involving an Allosaurus and a group of chameleon-like Ceratosaurus, The Journey from 2009 showed the annual migration of various Cretaceous dinosaurs herds to new feeding grounds, and Ancient Egyptians from 2015 depicted a brief period in the life of a Spinosaurus. While the first two stories partially anthropomorphized their non-human protagonists in their overly violent action and motivation, subsequent stories were told closer to the tradition of animal documentaries, attempting to avoid uncharacteristic animal behavior and interactions. The paleontological background is not explained further. Instead, the reader is challenged to extract all information from the colorful dynamic drawings (Fig. 6c). A similar approach was used in Cretaceous (Galusha, 2019) which tells the story of a Tyrannosaurus family struggling with a group of marauding Albertosaurus and obtrusive dromaeosaurs of all sizes. The pace of the story is further driven by the creative and dynamic use of panels (Fig. 6d). Another text-reduced Tyrannosaurus adventure is Love: The Dinosaur, where the vicious lead character interacts with more comic-relief dinosaurs to finally witness the inevitable asteroid impact (Brremaud and Bertolucci, 2017).

Figure 7Comic science books. (a) Large-format comic-style illustrations with concise text blocks in plain language can be found in Classics Illustrated Special no. 167A, 1962 (Classics Illustrated™ & © First Classics, Inc.). (b) Comic-like realization of the French animated series Once Upon a Time… Man, with all the quirks and loveliness that made the original so unique (© 2022 Soleil Productions/Splitter Verlag/Jean-Charles Gaudin/Jean Barbaud). (c) Evolutionary process of conquering airspace by pterosaurs as a graphically homogenized collage of cultural images of early aviation, mythological flying creatures, and schematic paleontological depictions including old and more recent reconstructions in Jens Harder's Alpha… Directions (© 2010 Carlsen Verlag). (d) Creative and at the same time comprehensive knowledge transfer on paleontological topics succeeds Abby Howard in her Earth Before Us book series no. 1 Dinosaur Empire! (© 2017 Abby Howard). All rights reserved.

Comic science books

Paleontological information has also been conveyed through a direct implementation of popular science book content in comic style. For example, an adventurous story with (intrusive) human protagonists can be abandoned in favor of imparting knowledge transfer through panels with text boxes. Classics Illustrated used this concept twice to present a volume on paleontological knowledge of its time: in Classics Illustrated Issue no. 19, The Illustrated Story of Prehistoric Animals from 1959, and in its successor, Classics Illustrated special no. 167A Prehistoric World from 1962 (Fig. 7a). Several chapters present the history of paleontology, the evolution of life, and the history of humankind in comic book form. In the comic adaptation of the 1978 French animated series Once Upon a Time… Man, the history of the earth before the appearance of humans was summarized in panels on several pages in the first volume (Gaudin et al., 2021), together with the series actors and the characteristic time clock (Fig. 7b). More recently, a more reflective account was provided in Alpha … Directions by Jens Harder, detailing the evolution of life up to the appearance of humans. Alpha used classic iconic depictions from books, articles, movies, TV shows, and also other comics to summarize concepts and mechanisms for evolution and the development of life according to current understanding in collages of science and pop culture. Short accompanying sentences articulate the main idea or message of each collage. (Fig. 7c; Harder, 2010). Another ambitious science comic, Evolution: The Story of Life on Earth (Hosler et al., 2011), provides insights into evolutionary processes on Earth, including paleontological topics, through black and white panels. The content covers highly complex processes in an understandable way through entertaining one-liners of extant and fossil organisms, presented and explained by an alien scientist in his holographic museum. In Science Comics: Dinosaurs (Reed and Flood, 2016), the narrative structure follows the history of scientific discoveries. The scientists portrayed, and sometimes even the dinosaurs, were given speech bubbles to convey relevant information. In the Earth Before Us trilogy by Abby Howard (Howard, 2017, 2018, 2019), we follow a scientist and a young girl through the geological eras. Readers get information about evolution, experience the variety and beauty of these lost worlds, and learn about the pronunciation of Latin names (Fig. 7d). Even a glossary is provided. While most information is conveyed by the protagonists in speech bubbles, some pages depicting animals in a particular ecosystem resembling puzzle pictures.

Figure 8Genre potpourri. (a) Dynamic storytelling illuminates the story of the egg thief dinosaur Chirostenotes in S.R. Bissette's Tyrant no. 1, 1994 (S.R. Bissette's Tyrant® is a registered trademark of Stephen R. Bissette; Tyrant® story and art © 1994, 2022 Stephen R. Bissette). (b) A look at the diverse living world of the Triassic in Matteo Bacchin and Marco Signore's Dinosaurs no. 1 The Journey: Plateosaurus, 2008 (© 2008 Matteo Bacchin/Marco Signore). All rights reserved.

Genre potpourri

The previously mentioned comic styles can also be mixed (i.e., a documentary-style narrative storyline with supporting text boxes supplemented by textbook-style background information). Marvel's Dinosaurs, a Celebration, a four-issue series on standalone dinosaur comic narratives by various artists and authors, was first published in 1992. Each issue contains four short, visually varied stories about different taxa, accompanied by blocks of descriptive text, and textbook-style pages on different paleobiological topics alternating with the stories. Stephen R. Bissette's Tyrant from 1994 tells the story of a breeding Tyrannosaurus and an egg-hunting Chirostenotes in four issues (Bissette, 1994), with ultimate consequences for one of them (Fig. 8a). The monochrome story focuses on these protagonists but also highlights other creatures such as insects, spiders, or turtles of the Cretaceous ecosystem. Finally, an entire volume is devoted to the development of the embryo in the egg, which is probably unique in its complexity in the comic field. Scientific information about the animals and their behavior is provided in an appendix to each issue. The book series Dinosaurs (Bacchin and Signore, 2008) devotes each of the six volumes to a particular Mesozoic ecosystem centered on distinct dinosaurs, Plateosaurus, Archaeopteryx, Allosaurus, Scipionyx, Argentinosaurus, and the inevitable Tyrannosaurus. In each volume, about 40 pages of a graphic novel (Fig. 8b) are followed by 20 pages of extensive textbook with detailed background information on the depicted taxa, their phylogenetic position, size comparisons, and general information on dinosaur evolution and paleontology. Finally, there is Mimo on the dinosaur trail (Mazan et al., 2016) about the results of the dinosaur excavation in Angeac–Charente, France. The Ornithomimosaur Mimo and his Carcharodontosaur friend Hector face an unknown danger together. The Cretaceous ecosystem is introduced as this story develops. After the comic section with text blocks and speech bubbles, making up almost half of the volume, there is an illustrated outline of the fauna followed by an account in sketchbook form of the real excavation with explanations of the work steps and an introduction of the human participants.

1.4 Graphic novels as a tool for teaching science

Today, paleoart is the most commonly used medium to communicate paleontological topics to the public. It can not only provide ideas about the ecosystems of the past but it can also help to increase interest in them (Berta, 2021). Therefore, it is obvious to use this medium of science communication in the form of a graphic novel. Research institutions address diverse target groups and educational levels in order to interest a broad audience in their research activities and findings. In this way, they break down barriers – including invisible ones such as language barriers – and can offer scientific content in a way that engenders equal opportunities and self-determined participation (Leidner, 2007; Metzger, 2016). Through this form of inclusion, every individual level of receptivity, needs, and knowledge are equally addressed in a format-friendly manner. Interested readers can thus approach specialized topics from different perspectives. This enables readers to independently experience content and gain knowledge. Simultaneously, it helps the pursuit for greater inclusion in our society (Abel and Klein, 2016; Wong et al., 2016; Metzger, 2016).

Our sensory nervous system is stimulated by a variety of sensory data. In that process, our senses automatically and constantly carry out selection processes of incoming information (Kahlert, 2000). Graphic novels are especially suited to focus our attention on specific senses. Images, in particular, often show something unexpected and can either complement or challenge prior knowledge, which in turn can trigger emotions and increase interest. Books and images can thus be used creatively as didactic material in the classroom. For example, a graphic novel with a scientific background may serve as a valuable complementary tool in the classroom, even when not directly related to the curriculum (Tatalovic, 2009).

Museum and collection knowledge transfer necessitates creating access to knowledge through a variety of aesthetic forms of presentation. These forms range from dioramas and room-filling illustrations to graphic literature such as graphic novels with page-filling images with little to no text. The latter can increase interest in technical topics and improve reading comprehension (Abel and Klein, 2016; Wong et al., 2016). Moreover, a graphic novel finds its readership among adults and yet does not exclude children, teens, and families because very little text comprehension is required (Abel and Klein, 2016; Wong et al., 2016). Haptic experiences with paper are often described by children as authentic and real, and therefore preferred for learning, as compared to viewing digital books (Sax, 2016). The latter ultimately remains dependent on the technology used and its availability.

Studies show that comics are suitable for teaching natural sciences to children (e.g., Farinella, 2018; Spiegel et al., 2013; and references therein). Even the often difficult-to-reach target group of young adults (often referred to as the virtual generation in the age of smartphones and digital media) can be addressed by means of graphic novels (Yang, 2008). Young adults are stimulated in their imagination by the illustrations and receive the content through independent exploration (Tatalovic, 2009; Short and Reeves, 2009). The general suitability for a diverse community of interest within a wide variety of backgrounds lies in the anchoring of comics in everyday life (Tatalovic, 2009). This broad audience wants to be met by adequate forms of communication and be encouraged to think about scientific content (Tatalovic, 2009).

Barrier-free access can be achieved by offering at least two sensory styles (two-senses principle; Metzger, 2016): an illustrated book with a reduced amount of text (for example, an exhibition catalog) can be picked up repeatedly and continues to function as a mediator while creating memories. The combination of images and reduced text also supports student learning (Wong et al., 2016). Science communication can use this multimedia approach to communicate topics with a lasting effect, especially since much more information can be conveyed in a picture than in a length-limited text. Graphic novels can increase interest in a topic through this interplay of image and text (Wong et al., 2016).

However, illustrations can still leave room for misinterpretation (Wong et al., 2016) and are therefore often only a complementary element to the communication of knowledge. This element, created through the collaboration of artists and scientists, gains credibility and authenticity in interaction with original objects, dioramas, and reconstructions (Klein, 2004; Berta, 2021). While dioramas or individual drawings tend to freeze a particular moment in time (Abel and Klein, 2016), a continuing story in a graphic novel allows for a change in perspective and better represents the multi-faceted nature of extinct organisms and ecosystems.

2.1 Motivation

As laid out in Sect. 1.4, graphic novels possess several benefits for science communication. In other natural sciences, the use of such educational graphic novels is more widespread. Environmental sciences, for example, lead the way. They do not only cover the climate crisis (e.g., Squarzoni and Whittington-Evans, 2014) but also general environmental work (e.g., Bertagna and Goldsmith, 2014), waste problems such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (Allison, 2012; Harris and Morazzo, 2013), severe changes in the biosphere (Kurlansky and Stockton, 2014), or suggestions of personal changes to reduce the carbon footprint (Dávila, 2011).

While guide books for the creation of graphic novels exist (e.g., McCloud, 1993, 2006), together with countless online blog posts and videos, we (Oliver Wings, Joschua Knüppe, Henning Ahlers, Arila-Maria Perl, Jan Fischer) did not use any of them actively in the creation of our book. Strangely, however, special literature regarding the creation of educational graphic novels does not seem to exist. To remedy this situation, we would like to share what we learned in creating our graphic novel and from a survey among the readers of this book.

The origin of our graphic novel lies in the active science communication that was carried out continuously during a paleontological research project about the dinosaur Europasaurus (see Sect. 2.2). This science communication involved not only regular press releases about new discoveries and technical articles but also talks and guided tours at the actual excavation site. The idea for a graphic novel was born after several years of exchange with the interested public. Our plan was to create a colorful work that would be both exciting and scientifically plausible. Hence, this approach falls into the genre potpourri in dinosaur comics from Sect. 1.3. Most similar is the approach in Mimo on the dinosaur trail (Mazan et al., 2016), which has a similar purpose and presents the excavation results from Angeac–Charente in western France (Allain et al., 2022) with its diverse flora and fauna in an age-appropriate way. There are significant differences in content and style, but the overall aim of immersive presentation of excavation results is remarkably identical. At the time of the EUROPASAURUS graphic novel's idea development, Mimo was not known to us and thus served neither as a template nor inspiration. It shows, however, that different people can independently develop similar ideas for transferring knowledge.

We decided on several basic parameters: (1) a documentary approach without anthropomorphized main characters, (2) a calm narrative style, and (3) the integration of scientific facts and references to actual fossil finds. Because only dinosaur books up to elementary school age were available on the German book market, our goal was to reach an older audience while also attempting to close the gap towards the specialized literature. However, the target group of our book was all people interested in the geological past, visual media, and/or illustrated works. Special focus was given to children from about 10 years, teenagers, and young adults, who often seem to have outgrown their dinosaur enthusiasm from early childhood. These young readers are able to experience the life of dinosaurs visually and enjoy easily accessible media content such as graphic novels and digital motion comics. Readers are required to have little or no prior knowledge of the subject. The content is easily understood through the narrative in pictures and aims to spark interest in more information. Even without reading the text, the book's design allows readers to follow the story. The focus of a graphic novel is of course on the graphic narrative part, but at the same time, background information in the appended factual section includes state-of-the-art research results in easy language. From the beginning, the book was planned to be German–English bilingual in order to expand the readership beyond a German-speaking audience. With these ideas in mind, we developed several research questions and addressed them in an online survey (see Sect. 2.3).

2.2 Scientific background

The Europasaurus project researches one of the most important Mesozoic sites for fossil vertebrates in Europe – the Langenberg Quarry at the northern rim of the Harz Mountains near Goslar in Lower Saxony, Germany. The peculiarity of this site is the inclusion of fossils of terrestrial vertebrates such as lizards (Richter et al., 2013), crocodylomorphs (Schwarz et al., 2017), pterosaurs (Fastnacht, 2005), the dwarf sauropod dinosaur Europasaurus holgeri (Sander et al., 2006; Carballido and Sander, 2014; Marpmann et al., 2015; Carballido et al., 2020), and theropod dinosaurs (Lallensack et al., 2015; Gerke and Wings, 2016; Evers and Wings, 2020), which are limited to a few layers next to commonly occurring marine fossils (Wings and Sander, 2012). The vertebrate remains were transported into the shallow marine depositional environment during the Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic, about 154 million years ago; Zuo et al., 2018). At that time, Europe was still a tropical archipelago. The terrestrial fossils came from a nearby island and, in addition to land plants, include predominantly the remains of dinosaurs but also many other vertebrate groups. Bones and teeth of the small sauropod dinosaur Europasaurus are particularly common. With a maximum height of 3 m and a length of 8 m, this macronarian sauropod was much smaller than its closest relatives, who rank among the largest land animals of all time. Food sources of Europasaurus were probably limited on the island, which may have led to island dwarfism over time – a recurring pattern throughout evolution (Sander et al., 2006). The discovery of the first Jurassic mammals in Germany (Martin et al., 2016, 2019, 2021a, b) and a number of other new taxa added to the success story of this research project. The large number of unusual and well-preserved fossil finds, which due to their often fragmentary nature reveal little to non-specialists, asked for a visual reconstruction of the living world of that time. A grant for innovative high-profile scientific outreach allowed the realization of a special project: the graphic novel EUROPASAURUS – Life on Jurassic Islands (Wings and Knüppe, 2020), presenting the results of many years of research on fossil organisms from Langenberg and their Late Jurassic ecosystem in an easily accessible form.

2.3 Methods and ethics

Because several of our ideas and reasoning in creating this graphic novel were rather guesswork than solid facts, we decided to ask our audience some questions via an online survey.

The background to the survey was centered around the following questions:

-

Are graphic novels as analog media generally of interest and is this interest age dependent?

-

In the opinion of the interviewees, are graphic novels suitable for conveying (natural) scientific content?

-

In the opinion of the interviewees, are bilingual graphic novels also suitable for teaching a foreign language?

Almost 2 years after the publication date of the book, we started to address these questions in an online questionnaire. Fortunately, it was possible via social media to reach out to a large number of readers, and an online survey was designed using Google Forms. The aim of the anonymous online survey was to record the general impressions of the graphic novel in terms of its design and structure on the recipients. Furthermore, the suitability of the book for conveying scientific content and foreign language skills was evaluated. The survey was carried out as a questionnaire with mostly five-point Likert scales. The collected data were processed using Microsoft Excel and evaluated with the statistical software PSPP with regard to Pearson correlation (r) of the scales and significance (p), with 0.5< IrI ≤0.8 for a clear linear connection and 0.8< IrI ≤1.0 for high to perfect linear connection of the scales. A p value <0.05 is considered significant. In addition, the participants had the opportunity to verbally formulate comments regarding three other aspects: (1) is there anything in the book that particularly stuck in your mind? If yes, what was that?; (2) what did you like the most?; and (3) what could still be improved? The answers to these open questions were addressed in a thematic analysis. Furthermore, we started a preliminary thematic analysis of the reviews of the book on the Amazon website.

All information was treated as strictly confidential in accordance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and according to the guidelines of the Department of Didactics of Biology at the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg. All research results and survey information were only used in an anonymous form, the identification of individual participants in the questionnaire is impossible.

2.4 Survey results

A total of 152 persons participated in the survey (see Supplement for complete dataset). This number is well above the recommended minimum number of 120 samples for statistical analyses and thus allows 90 % confidence intervals for the endpoints of the normal range (Reed et al., 1971). The majority (69.7 %) of the participants were male. Of all participants in the survey, more than half (52.3 %) consider themselves to have very good knowledge of paleontological topics, another quarter of the participants (25.2 %) estimated their paleontological knowledge still as good.

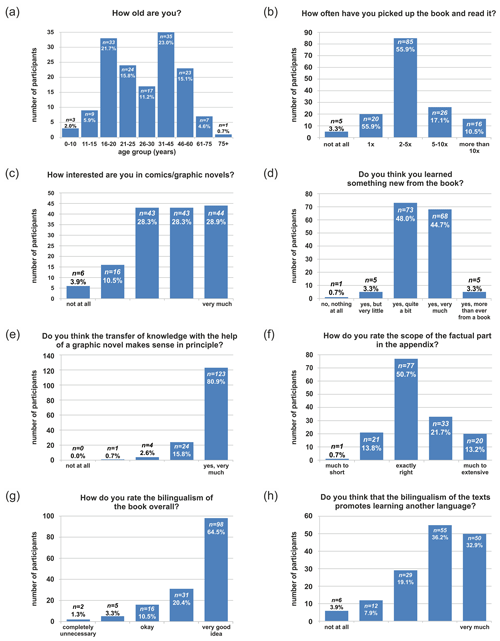

Surprisingly, the age structure of the participants was quite mixed (Fig. 9a), with the group of 16–25-year-old making up over one-third (37.5 %) and those over 25 making up just over half (54.6 %). Most readers read the book several times (Fig. 9b). The frequency of engagement with the book was not dependent on age (p=0.577). The basic interest in graphic novels or comics (Fig. 9c) is also not significantly (p=0.325) age dependent among the test persons. Within this sample, overall rating (r=0.037; p=0.652), extent of prior knowledge (; p=0.202), and interest (; p=0.126) were found to be equally independent of age.

The estimated increase in knowledge through the graphic novel (Fig. 9d) of the remaining 22.5 % of the respondents with no or little prior knowledge, however, differed only marginally from that of the entire sample (3.45 vs. 3.46 in the mean). Therefore, an increase in knowledge can be assumed for all respondents to about the same extent, which then, however, probably refers to different, previously unknown areas. Overall, 16.4 % of the respondents found the graphic novel interesting and 80.9 % even very interesting. An almost identical picture emerged from the evaluation of the book in the form of awarding stars (* – worst evaluation, ***** – best evaluation), with 82.5 % awarding five stars and 15.8 % awarding four stars.

Regarding the suitability of graphic novels for science communication, over 96 % of the participants found it to be a useful (15.8 %) or very useful (80.9 %) tool for knowledge transfer (Fig. 9e). This underlines the applicability of graphic novels for knowledge transfer, as significantly fewer participants indicated a great (28.3 %) or very great (28.9 %) interest in these media when asked for their general interest in graphic novels or comics (Fig. 9c). An extremely high significance was shown with the participants, who indicated a basically large interest in comics and graphic novels, these evaluated this book as very interesting (p=0.000). The extent of the factual part was considered to be enjoyable by most readers (Fig. 9f).

A preference for the native language, both in the graphic and in the factual part of the book, could be recognized. However, about a third of the participants (29.6 %) read also all texts of the graphic part in the other language; with the factual part, it was still about a quarter of all participants (23.7 %). The bilingualism of the book as a whole was evaluated by the predominant number of the survey participants as a good (20.4 %) or very good idea (64.5 %) (Fig. 9g). Furthermore, about two-thirds see the bilingualism as rather positive for the learning of a foreign language (36.2 % – beneficial and 32.9 % – very beneficial) (Fig. 9h). There was a strong correlation between engagement with graphic and factual sections in the foreign language (r=0.89).

With regard to the assessment of the appropriateness of the pricing, at least the test persons who gave high ratings felt that the book was appropriately priced (p=0.000) and would buy it again or recommend it to others (p=0.000). The situation was different when respondents were asked if they would look at the book with children. Even though 52.6 % of the respondents would definitely look at the book with children and 30.3 % stated that this was still likely, there was no dependence on the general evaluation (p=0.716; r=0.030).

In addition to the survey, the participants had the opportunity to verbally comment on three different aspects of their engagement with the graphic novel. The first question related to scenes or sections in the book that were particularly memorable. Of the participants, 108 commented on this. From the responses, the following categories of design or plot were highlighted based on the frequency of mentions (more than 10 mentions). Frequent positive statements about the design referred to the realism or detail of the drawings (22 mentions; 20.4 %), while 21 mentions (19.4 %) emphasized the artistic design in the form of different perspectives and views. The depiction of the biodiversity of living creatures was also felt to be particularly impressive (16 mentions; 14.8 %). In addition, many different individual depictions were mentioned, the most common of which was the depiction of the thunderstorm (pages 72–75; 20 mentions; 18.5 %).

The second question was aimed directly at what single aspect the participants liked best. Among the 120 responses, more than 10 mentions each fell into four main categories: The quality of artistic representations was mentioned by 59 (49.2 %) participants, 22 (18.3 %) participants particularly highlighted the representation of biodiversity, 21 (17.5 %) participants liked the factual part the most, and 12 (10 %) people preferred the story.

Of the participants, 97 also answered the last question, which asked for suggestions for improvement. In this regard, 42 people (43.3 %) stated that they could not make any suggestions for further improvement in terms of complete satisfaction with the graphic novel. A more extensive factual section was recommended by 10 persons (10.3 %), while 2 persons (2.1 %) felt it was too long. Another five people (5.1 %) suggested even more panels.

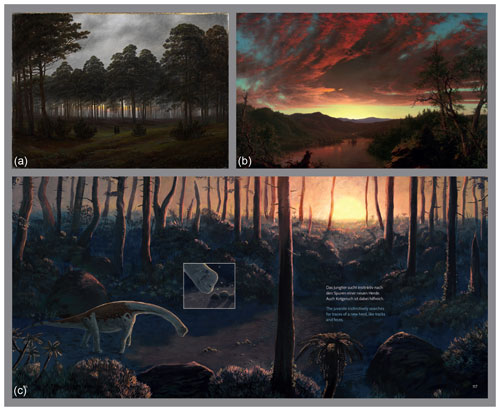

Figure 10Comparison between paintings that influenced the EUROPASAURUS graphic novel and one of its final double page's creations. (a) Der Abend, Caspar David Friedrich, 1821 (public domain). (b) Twilight Wilderness, Frederic Edwin Church, 1860 (public domain). (c) Juvenile Europasaurus in the Evening, artwork by Joschua Knüppe, 2020, EUROPASAURUS graphic novel, pages 116–117 (© Wings and Knüppe, 2020).

On the Amazon webpage, the EUROPASAURUS graphic novel has as of now (11 November 2022) 44 ratings with an average score of 4.6 out of 5 stars. Fourteen customers left written reviews, of which nine originated in Germany, two are from Great Britain, two from the USA, and one from Japan. Among the 12 nonprofessional reviews, 4 positively emphasized the bilingualism, 8 praised the content approach (scientific background, story, topic), and 4 commented positively on the factual part (stirring interest, appreciation of the scientific elaboration). Two reviewers appreciated the scientifically correct representation of the actual processes, especially the (bloody) acquisition of food by predators via hunting prey, whereas also two people doubted the correct representations (e.g., of the animals). Regarding the possible target group, four reviewers suggest everyone who likes dinosaurs (including adults), while also four reviewers see it as suitable preferably for children at least 6 or 7 years old. One person was inspired to look into the fossil site and planned to visit it. Two reviews recommended the book to others or did buy it again.

Figure 11Comparison between paintings that influenced the EUROPASAURUS graphic novel and one of its final double page's creations. (a) Staffa, Fingal's Cave, William Turner, undated (public domain). (b) Fishermen at Sea, William Turner, 1796 (public domain). (c) Northeaster, Winslow Homer, 1895 (public domain). (d) Storm over the Jurassic Sea, artwork by Joschua Knüppe, 2019, EUROPASAURUS graphic novel, pages 74–75 (© Wings and Knüppe, 2020).

2.5 Discussion of survey results

Based on the results of this survey, the research questions formulated at the outset (see Sect. 2.3: Methods and ethics) can be answered as follows: graphic novels, and this book in particular, meet with a very high level of interest due to both the quality of the design and the structuring of the content, and this is independent of both the age and prior knowledge of the readers. In the opinion of the interviewees, graphic novels are quite suitable for conveying scientific content and, at least in this case, lead to a clear increase in knowledge among both pre-educated persons and laypersons. Moreover, bilingualism is seen as a good means of teaching a foreign language.

However, it should be noted that the selection of test persons does not represent a random cross-section of recipients, but that the participants decided to participate voluntarily and thus possibly have a generally higher interest in graphic novels and/or paleontology.

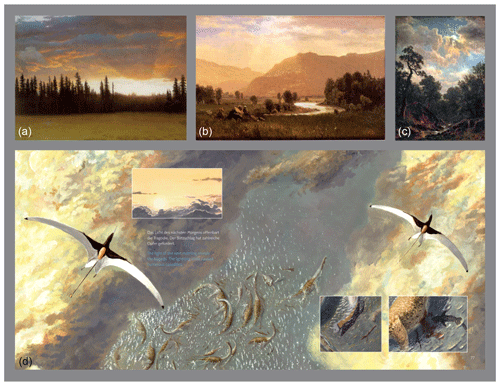

2.6 Storytelling with facts and fiction: the balance between entertainment and scientific accuracy

For an especially vivid impression of this Jurassic ecosystem, the situations and behaviors shown in the images were chosen to be as diverse and visually creative as possible. In addition to fossil finds, analogies and comparisons with living animals and comparable habitats, and examples from the history of art and paleoart, served as inspiration. For example, the painting Der Abend by Caspar David Friedrich served as an initial inspiration for the composition of a forest scene at dawn, while the colors in this picture were mostly inspired by classic landscape paintings of Edwin Church (Fig. 10). A storm scene (Fig. 11) is a loose homage to the sea paintings by William Turner and Winslow Homer, while clouds on the following page can partially be traced back to influences by Albert Bierstadt (Fig. 12). Overall, the work of the Hudson River School, a group of landscape painters that included Church and Bierstadt (Avery et al., 1987), left an impression on many pages of the graphic novel. On the paleoart side, the work of Douglas Henderson was an important inspiration, especially his handling of light and shadows, structure of the images but also, for example, his use of dead wood. Additionally, major paleoart influences came from John Gurche's, John Conway's, Mark Hallett's, and Todd Marshall's works.

Figure 12Comparison between paintings that influenced the EUROPASAURUS graphic novel and one of its final double page's creations. (a) California Sunset, Albert Biertstadt, undated (public domain). (b) Figures in Hudson River Landscape, Albert Bierstadt, undated (public domain). (c) Moonlit Landscape, Albert Bierstadt, undated (public domain). (d) Pterosaurs over the Sea, artwork by Joschua Knüppe, 2019, EUROPASAURUS graphic novel, pages 76–77 (© Wings and Knüppe, 2020).

We hoped that the graphic novel (although inevitably rendered outdated sooner or later by scientific advances) would provide a visually and intellectually appealing medium that will continue to excite future generations about the fossil flora and fauna of the Langenberg Quarry and paleontology in general.

The plot of the story revolves around the experiences of a juvenile Europasaurus individual. Interwoven with subplots of various protagonists such as a series of predatory dinosaurs, marine crocodiles, turtles, pterosaurs, small mammals, lizards, and dwarf land-dwelling crocodyliforms, the story thus provides an overview of the entire ecosystem. Major events such as a storm, a lightning strike, and a fire serve as overarching plot highlights.

Due to the demand for scientific accuracy in the presentation (in contrast to a classic comic book), only limited means were available to create an emotional connection between the story's main character and the reader. Neither dialog can be conveyed with typical comic speech bubbles nor should emotions in the animals be portrayed in a pronounced way. Therefore, to bind the reader to the main character and create empathy, fictional elements of the so-called hero's journey were used. At the beginning, the hero, a young Europasaurus, lives comfortably under the care of the herd. A stroke of fate leaves the protagonist on its own. The young animal must outgrow itself and continue on its way alone. Although the course of this plot is fictional, it always remains realistic and plausible. For example, a lightning strike as depicted killing the herd in our book is considered the most plausible scientific explanation for the Europasaurus bone bed (Wings and Knüppe, 2020), which contains remains of at least 21 individuals representing all ontogenetic stages (Scheil and Sander, 2017).

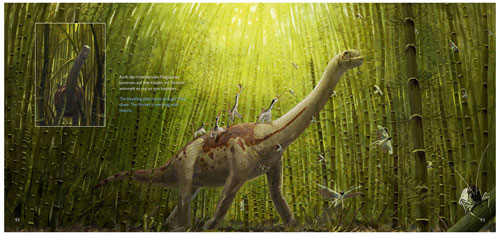

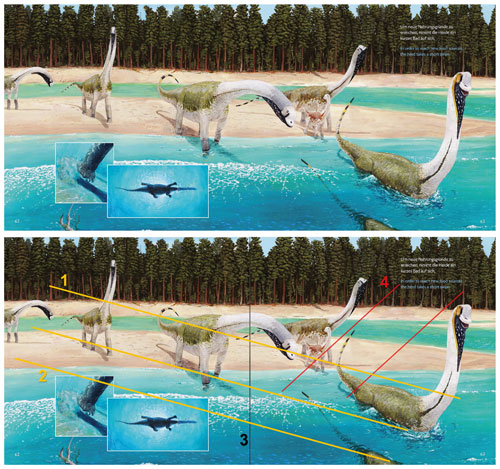

Figure 13(a) Example of a final double page in the book. (b) Schematic structure of this double page: the structure of the basic illustration and the movement of the Europasaurus herd correspond to the usual western reading direction from left to right. The reader starts in the familiar way of looking at the top left and following the diagonal direction of action across the center of the picture to the bottom right (1). As graphical compensation, two inset panels were placed at the bottom left, which in turn are set from left to right in their reading direction (2). The left panel is placed behind the right panel, supporting the desired reading order. The panels illustrate a detail and another perspective of the action in the basic illustration. When designing double pages, it is always important to ensure that the area in the middle of the picture does not contain crucial information, as this might otherwise be lost during binding of the book (3). The text block in the upper right corner (4) provides additional graphic balance. The necks of the sauropods point up to the text block. They represent the last element in the sequence of perception on the double page. The text offers additional information about the action of the herd action, namely their motivation. Horizontal lines, resulting from the surf, the beach, and the tree line, stabilize the overall presentation of the double page with its otherwise diagonal impression (© Wings and Knüppe, 2020).

Figure 14The color scheme of the first 18 double pages of the book. Changing the dark distance view at the beginning into deep blue and later green colors. A warm sunset light closes the first day, followed by dark night scenes. The second day starts again with warm colors, whereas green and yellow dominate the landscapes on the following pages. For more information, see the main text (© Wings and Knüppe, 2020).

2.7 Storytelling with pictures: how to find a unique style

From the beginning, a hybrid between comic book style and non-fiction book detailed paleontological illustrations was planned. The square format of the book unfolds to double pages in wide format. Each double page was used in full size for a basic illustration showing a core message (Fig. 13a). In this basic illustration, small comic panels are placed that either advance the plot or provide further insights into the ecosystem. Occasional text blocks offer further information. We refrained from using a typical comic panel-to-panel structure on a white background and the distinctive hand-lettered black font set in white speech bubbles or boxes. Instead, all design elements were subordinated to the overall impression of the double pages and later adapted for a visually balanced outcome (Fig. 13b).

Our goal during the course of the story was to display the broadest possible spectrum of different color and light moods in order to present them in a visually interesting way, reaching a length of around 140 pages (around 70 double pages).

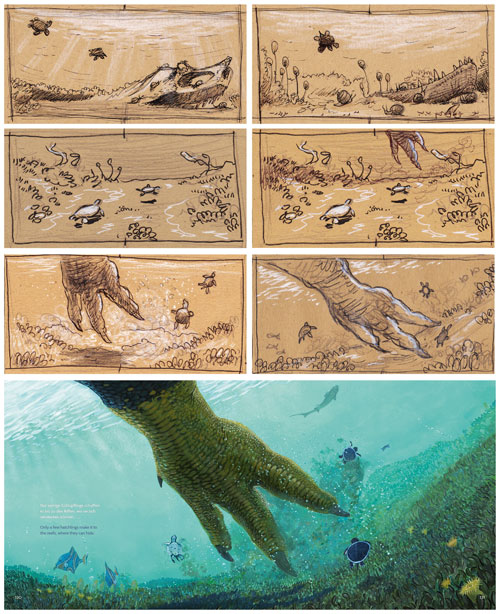

Figure 15The evolution of storyboard sketches sometimes included many different versions for a particular scene. This double page combines the end of a turtle hatchling storyline with the introduction of (swimming) torvosaurid theropods (© Wings and Knüppe, 2020).

Time of day, weather, landscape, and flora, and the change from wide settings (such as landscapes) to detailed representations of small animals were used to create constantly new image themes in accordance with the storyline. The dramatic composition and representation of the main elements of the story essentially controls how long the reader stays in such a world of pictures, colors, and moods.

This principle becomes evident on the first 18 double pages (Fig. 14): We started with a picture dominated by black, showing the Earth from a distance during a sunrise (1). We open the curtain and accompany a marine crocodyliform Machimosaurus on its journey from the ocean (2–3) through a river delta (4) into the hinterland of an island. There in a lake, the individual first fights (5–6), and then mates (7). On pages 2 and 3, deep blue tones depict the ocean, which then gradually merge into green colors, illustrating the inland areas. The mating takes place in the romantic warm light of a sunset (7). The first seven double pages illustrate the behavior of the Machimosaurus over the course of a day. During the night, the small multituberculate mammal Teutonodon meets a sleeping (dying) Machimosaurus (8). Now the focus switches to Teutonodon, and we accompany it on its prowl through the night (9–11) until the mammal reaches its den, where it takes care of its offspring and falls asleep among them (12–13). The nocturnal images are mostly implemented in close-up views with detailed depictions. In contrast, the following dawning new day is introduced in a large wide-angle landscape shot (14). The subsequent four double pages show the Europasaurus herd near the mammalian den. The story continues on a sunny day in a light forest dominated by green (plants) and yellow (ground) colors (15–18).

From the beginning, all images were planned and created to stand alone (i.e., without text) in order to use the visual medium to its maximum effect. In some places where short explanations could contribute to a better understanding of the storyline, reduced text was added to the sequence of images in a final production step. The factual section following the narrative graphic novel part explains the main scientific results of the Europasaurus project in an easily understandable way. Its bilingualism (German/English) ensures easy access of an international audience to the background information.

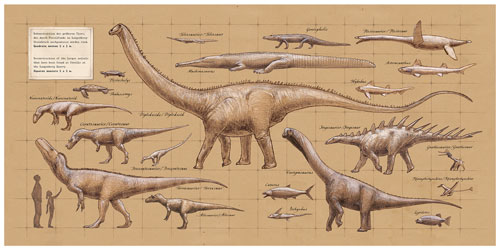

Figure 16The front flyleaf of the book introduces all larger vertebrates in the same scale (© Wings and Knüppe, 2020).

2.8 How to maximize awareness: social media and exhibitions

The book was published in November 2020. It contains 184 pages, 38 of which comprise the scientific background. At the same time the book was published, social media activities on various channels (Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube) were started for promotion.

We also provided free access to half of the book's content on YouTube as animated motion comic videos. In four episodes, short stories about different organisms in the ecosystem of the time are told: episode 1 deals with the marine crocodyliform Machimosaurus, episode 2 with the small nocturnal mammal Teutonodon, episode 3 with Europasaurus and predatory Ceratosaurus, and episode 4 focuses on a natural disaster that probably took place at that time and caused the mass occurrence of fossil bones. Each of the four videos is available in English and German versions. The free online access helps to achieve a large international distribution (link to the first English episode on YouTube: https://youtu.be/ftkxBgQJslM, last access: 4 May 2023; all four episodes combined are uploaded in the TIB AV-Portal at https://doi.org/10.5446/61345; Knüppe et al., 2021). Beyond presentation in digital media, the detailed life restorations beg to be presented on a larger scale in the context of exhibitions. Some Europasaurus works were already on display in the special exhibition KinoSaurier at the Lower Saxony State Museum Hannover, Germany, and the Natural History Museum in Vienna, Austria. Overall, the responses to the graphic novel have been very positive, and we hope that through our work we can also contribute to a better understanding of prehistoric times in Germany.

2.9 Insights into the production process

A small team of people, whose different professions complemented each other, created the graphic novel EUROPASAURUS – Life on Jurassic Islands. Vertebrate paleontologist Oliver Wings, an expert on the fossil biota of the Langenberg locality including Europasaurus, provided the scientific background. Paleoartist Joschua Knüppe illustrated press releases about the newly described taxa from the Langenberg Quarry for several years, providing him with a solid base of knowledge for this project. Knüppe created a total of 275 detailed illustrations for the comic section and a further 80 illustrations for the factual section of the book. Media designer and art director Henning Ahlers was responsible for the consistency of the narrated story, done through visual storytelling with a continuous arc of suspense and a coherent color scheme. Museum educator Arila Perl took care of the design and typesetting of the entire book. The creation of the book took a total of 3 years from the conception of the first chapter to the final print. Up to two dozen versions of storyboards for the respective storyline were created in advance before the final version of the illustrations were implemented as elaborate acrylic paintings. Due to the spatial separation of the team, video conferences were the primary form of communication. Even before the pandemic, these online meetings took place several times a week.

After collecting ideas and determining a first rough plot, storyboard sketches were created (mostly on brown paper) in order to precisely indicate the arrangement of light and shadow (Fig. 15). These early storyboards served as the basis for further discussions to detail and refine the story. Especially in the later developmental stages, traditional sketches were combined with digital ones, allowing the team to witness and discuss their creation through screen sharing.

Once the compositions and story of a section were finalized, the sketches were transferred onto large paper. Each double page was painted in 58.5×29.5 cm format, larger than their final book printing in order to ensure a higher detail density. During the early creation of the chapters, the base coat of paint was applied with large brushes. However, this often led to uneven color gradients and noticeable brush strokes, especially with darker tones. Eventually, we switched to the use of small synthetic sponges for the application of the first layers of paint. On top of these, a rough sketch of the composition was drawn and the first shapes of flora and fauna blocked in, starting with the scenery and ending with the main focal points of the painting. Here, a mixture of gouache, acrylic paints, watercolors, and colored pencils was used. After shapes and shadows were depicted, details like skin patterns and textures were added. This later stage often went through a few discussions to ensure consistent quality and effectiveness of the compositions. After the drawing stage was complete, final digital high-resolution scans of the picture were produced accompanied by a first rough color correction, retouches, and sometimes further digital enhancement. The final step before publication consisted of detailed retouches (digitally removing dust particles, etc.) and color and brightness corrections. The front flyleaf (Fig. 16) and two of the double pages (Figs. 17, 18) give examples of the final outcome.

Since their scientific discovery almost 200 years ago, dinosaurs and other extinct taxa have always inspired our imagination, and they will likely continue to do so in coming generations. Their common appearance in pop culture provides an unparalleled opportunity for transmitting paleontological research to the public. Projects like the EUROPASAURUS – Life on Jurassic Islands graphic novel provide the means to correct common misconceptions of fossil organisms, their interactions, and former ecosystems in the public eye.

Such publications also combine useful sources of information and fun in education. We hope that our experiences may inspire others to create similar works on other paleontological topics or even other disciplines of geoscience. This is further underlined by the past success of comics about past worlds and their inhabitants, whether as adventure, illustrated science book, or self-narrative documentary.

Data were collected from the available comic and graphic novel literature. We acquired permissions for the depicted images from the current copyright holders to the best of our knowledge. Most works are still publicly accessible to purchase.

The video supplement at https://doi.org/10.5446/61345 (Knüppe et al., 2021) contains all four episodes that Joschua Knüppe, Henning Ahlers and Oliver Wings created in 2021 in order to take viewers along for a journey into the Late Jurassic of Central Europe. It is based on their graphic novel EUROPASAURUS – Life on Jurassic Islands.

The complete set of questions used in the questionnaire about the EUROPASAURUS graphic novel (PDF file). Dataset containing all questionnaire answers (Excel file). The first sheet contains the raw dataset, the second sheet contains the same data processed for PSPP. The cover image for the highlight article is a collage of several pictures from our graphic novel with two speech bubbles added specifically for this purpose (© Wings and Knüppe, 2020). The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-6-45-2023-supplement.

OW, JK, HA, and JF conceptualized and designed the EUROPASAURUS graphic novel, AP carried out the typesetting of the book. OW and JF developed the idea for this article. JF provided the initial review of comics and graphic novels; JK provided the section on paleoart; AP provided the section about teaching science with graphic novels; and OW, JK, and HA wrote the section on the EUROPASAURUS graphic novel. JF, HA, JK, and OW prepared the figures for the article. OW, JF, and SK designed the questionnaire which was evaluated by SK. OW and JF prepared the draft and edited several pre-publication papers with contributions from all the other authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

The data used in this study were recorded on a voluntary and completely anonymous basis. The identification of individual participants in the questionnaire is impossible. Any personal information was treated as strictly confidential in accordance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and according to the guidelines of the Department of Didactics of Biology at the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

In preparing this article, considerable time was spent on obtaining the necessary permissions to reproduce copyrighted material in this open-access article in order to allow the reader to experience the various comics with their merits and peculiarities. We sincerely hope that we have not overlooked any claims, and we would like to thank the many people, artists, and publishers for further information and generous permissions to use their graphics in our article. We thank the following people in alphabetical order: Anja Adam (Egmont Ehapa Media, Berlin), Verena Arzmiller (Carlsen Verlag, Munich), Matteo Bacchin (Milan), Mandy Barr (DC Comics, New York), Saskia Baumgart (Bulls Pressedienst, Frankfurt am Main), Bradford W. Berger (First Classics, Inc., Pioneertown), Meghan Chan and Kari Torson (Dark Horse Comics, Milwaukie), Ricardo Delgado (Los Angeles), Achim Dressler (Bocola Verlag, Klotten), Eckhard Friedrich (Bildschriftenverlag, Hannover), Tadd Galusha (Anchorage), Abby Howard (Charlotte), Irene Kahlau and Helga Uhlemann (Tessloff Verlag, Nürnberg), Mike Keesey (Los Angeles), Jim Lawson (Chesterfield), Robert Löffler (MOSAIK Steinchen für Steinchen Verlag, Berlin), Ted Rechlin (Rextooth Studios, Bozeman), Max Schlegel (Splitterverlag, Bielefeld), Mark Schultz (Clarks Summit), Stephanie Steinmetz (The Walt Disney Company (Germany), Munich), Stephen R. Bissette (Vermont), Rosemary Volpe and Erin Gredell (Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University), Rostislav Walica (Prague), Cathy Wilbanks (Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., Los Angeles), and Nadine Winns (Abbeville Press, New York).