the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Focus on glaciers: a geo-photo exposition of vanishing beauty

Gualtiero Böhm

Angela Saraò

Diego Cotterle

Lorenzo Facchin

Paolo Giurco

Renata Giulia Lucchi

Maria Elena Musco

Francesca Petrera

Stefano Picotti

Stefano Salon

Scientific research, respect for the environment, and passion for photography merged into an exceptional heritage of images collected by the researchers and technicians of the National Institute of Oceanography and Applied Geophysics (OGS). The images were taken during past scientific expeditions conducted all over the world to widen scientific knowledge in the fields of Earth and ocean sciences, to raise awareness on the environment and conservation of natural resources, and to mitigate natural risks.

In this paper, we describe a photographic exhibition organized using some of the OGS images to draw public attention to the striking effects of global warming. In the artistic images displayed, the glaciers were the protagonists. Their infinite greyish blue shades and impossible shapes were worthy of a great sculptor, and the boundaries with rocks or with the sea were sometimes sharp and dramatic and sometimes so nuanced that they looked like watercolours.

The beauty of the images attracted the attention of the public to unknown realities, allowing us to document the dramatic retreat of the Alpine glaciers and to show the majesty of the Arctic and Antarctic landscapes, which are fated to vanish under the present climate warming trend.

The choice of the exhibition location allowed us to reach a broad public of working-age adults, who are difficult to involve in outreach events. The creators of the images were present during the exhibition to respond to visitors' curiosity about research targets, the emotional and environmental context, and the technical details or aesthetic choices of the photographs.

- Article

(20344 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The route towards a sustainable world requires a profound change in the way we deal with the planet's resources, which will involve everyone; institutions, businesses, consumers, and citizens will be called upon to collectively create a new model of development.

In September 2015, the United Nations General Assembly approved the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, i.e. a plan of action that all countries (policies and citizens) have to respect in the coming years to achieve sustainable development by 2030 (United Nations, 2015). The Agenda 2030 is composed of 17 main Sustainable Developments Goals (SDGs) in areas of utmost importance for humanity and the planet. Action against climate change is at the core of Goal 13, which is to take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. In particular, target 13.3 suggests that countries “Improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction, and early warning” (United Nations, 2015). Limiting future global warming to 1.5 ∘C requires rapid, far-reaching, and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society, but it would imply clear benefits to people and natural ecosystems, while ensuring a more sustainable and equitable society (IPCC, 2013).

By the end of 2019, interest in climate change and the dangerous effects of present global warming had become very widespread. The actions of Greta Thunberg and the “Fridays for Future” movement played a primary role in increasing people's awareness and promoting public debates on this issue. In 2020, it became evident that an increasing number of people are making small but effective steps in the direction of plastic and emission reduction, energy saving, and environmental protection. The so-called “Greta effect” led to philanthropists and investors from the United States donating almost GBP 500 000 to establish the Climate Emergency Fund (e.g. Stuecker et al., 2019). The idea is to spread the money widely to many groups, in relatively small increments, for small but effective actions. However, just a few years ago, this topic was mostly ignored; notwithstanding the already high consensus among scientists about the anthropogenic impact on global warming (AGW), public opinion was not aware of it or denied its existence. The primary reason that induced people to deny AGW during public debates was the apparent lack of agreement between scientists (Cook et al., 2016, and references therein). We recognize that the problem of communication between scientists and the general public is an essential issue in many science fields. Lacchia et al. (2020) analysed the difficulties in communication between geoscientists and non-geoscientists. According to the study, public opinion about geosciences often focuses on the negative environmental impacts of geoscience activities (e.g. energy supply, mineral resource exploitation) rather than on their role in developing basic knowledge of our planet and for environmental protection. To overcome such prejudices, and in agreement with the recommendations for science communication (Dahlstrom, 2014), Lacchia et al. (2020) recommended that other geoscientists also include their feelings, such as their motivations for the research, when outlining the impact of their own studies on knowledge and society to reach a broader audience. Effective communication with a large audience can ensure the broad support necessary for policymakers to take the necessary actions once they are convinced of the firmness of the scientific results (Liverman, 2008).

The combination of science and art is becoming increasingly popular for improving the connection between science communicators and the public (e.g. Malina, 2010). Among the various strategies, photography is a practice of straightforward communication that is able to easily catch the interest of the public on critical questions. Furthermore, photography is the perfect combination of art and science because it naturally attracts people with different backgrounds or motivations. The proliferation of smartphones and software applications dedicated to image editing has made photography a common gesture in our lives. Every image can appear differently to the observers, eliciting emotional responses. Impressive photos can derive from either a scientific or artistic approach, but “great photos often come from a combination of both art and science” (Stone, 2017). The creation of a photograph requires emotion and imagination, although creativity and beauty can be engineered in postproduction using editing software. Several photo exhibitions have been organized during the past few years, by professional photographers and artists worldwide, in the framework of specific projects devoted to enlarging public awareness of the climate crisis, by using the art to strengthen the message (e.g. Macromicro non-profit Association, 2020) or to create an eye-opening performance to incite social and political change (e.g. Neudecker and Project Pressure Partnership, 2015). Other initiatives focused on integrating art and science, such as the Extreme Ice Survey (Balog et al., 2012, 2019), which produced a photographic book and a documentary that won an Emmy Award in 2014 (Chasing Ice, 2020). Online photographic collections from scientists are available through specific projects, such as those managed by the National Snow and Ice Data Center (2020), which are supported by NASA and the National Science Foundation (NSF) or by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center (2019) and which are focused on the Glacier National Park. Another photographic repository collected by scientists is managed by the European Geoscience Union (EGU, 2019). Every year, during the EGU General Assembly, after a contest to choose the most beautiful photo, the photos with the most votes are printed and freely distributed as postcards to reach a wider public and show the beauty of our planet.

Drawing on the rich image collection of the OGS, which is scientifically engaged all over the planet, we decided to organize a photographic exhibition that focused on glaciers and ice sheets distributed at different latitudes to convey a strong message to the public on the devastating effects of climate change on our planet; this aligns with the recommendation of Agenda 2030 and, in particular, with the already mentioned specific target 13.3 of SDG no. 13, relating to climate action.

Ice sheets in polar areas and mountain glaciers above 2500 m have been shown to react particularly rapidly to the present climate warming (Shepherd et al., 2018, 2020). For this reason, we specifically focused on images of glaciers, ice caps, and icebergs as an efficient way of communicating the perception of the fragility of such environments which are presently jeopardized by climate change. The originality of our exposition, when compared to the ones mentioned above, is that the creators are scientists involved in scientific activities during research cruises and not professional photographers. Our goal, in fact, was to close the gap between research and society; the exhibition became a way to bring scientists nearer to the public and, specifically, working-age adults, in an environment usually unrelated to science. The images were taken during scientific research activities on research vessels or in the field, and they reflect the intimate attitude and the sense of wonder of human beings in front of the supreme beauty of nature, combined with the artistic side of the scientist. During the exhibition, the visitors were able to satisfy their curiosity on the research aspects, the context in which the pictures were collected, the technical photographic details, and specific aesthetic choices. This paper presents a summary of this experience, which impacted both the creators and the visitors.

The National Institute of Oceanography and Applied Geophysics – OGS is a public research institute supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR). The institute is active in the research fields of geosciences of the solid Earth and oceans to increase scientific knowledge, mitigate geohazards, exploit and conserve natural resources, and raise environmental awareness from a sustainable development perspective. The OGS employs a staff of approximately 300 people, and it promotes research through the joint use of its main research infrastructure (i.e. research vessels and aircrafts and onshore and offshore monitoring networks).

Due to its long-term collaboration with the energy industry, the OGS has developed high technological competence and skills in acquiring, processing, interpreting, and modelling onshore (surface and borehole) and offshore geophysical and oceanographic data. The interdisciplinary character of the OGS has allowed it to provide fundamental contributions to the challenges of the present time. In particular, OGS research activities have enabled an assessment of the past and current state of the environment to define future scenarios, considering natural forcing and human activities, and to exploit the most advanced computing technologies for climate model data production and analysis at the local or global scale. Furthermore, multidisciplinary studies contributed to the definition of strategies to reduce the greenhouse effects of CO2 through its sequestration in geological storage.

In agreement with the general principles of the European Charter for Researchers and Code of Conduct, the OGS is extensively engaged in dissemination and communication activities. The OGS communication strategy includes the organization of and participation in public events to maintain an open dialogue with stakeholders, citizens, and young people and to share knowledge and outcomes in support of society. Among these, several dissemination events were performed within international initiatives, such as the European Researchers' Night, the Pint of Science festival, or local initiatives, such as the Trieste festival of the scientific dissemination (NEXT) or appointments with science in the historical cafès of Trieste.

The main elements of the communication process derive from the models of Shannon (1948) and Berlo (1960). The main elements are the sender (the person transmitting the message), the receiver (the person receiving the message), the message (the communication subject), the channel (the communication vehicle), and the context (where, how, and when the message is sent). The general difficulties of the scientific community in transferring their research results and insights are well known, and this is particularly true when the message concerns environmental issues and communication is addressed to the general public or politicians. Photographic books and exhibitions provide precious support for conveying knowledge because they allow the images to be observed and pondered more slowly. Photography, which is a channel of communication, uses a universal language that can reach a large number of people, especially today when the bulk of information is mainly conveyed through images. Indeed, photography is much more immediate than text, and it provides a volume of information that can be perceived at one glance and be quickly memorized. Therefore, we identified photography as a powerful and efficient channel for communicating the need to protect specific environments that are highly endangered by global change. During the selection of the photos for the exhibition, preference was given to high-quality images evoking emotions on natural beauty that could be lost.

Among the elements of visual communication, the context is as important as the message and the channel. In our case, the photographic exhibition was set up in a popular, often crowded workplace to reach the widest range of visitors, including working-age people who generally do not attend public conferences or other dissemination events. The exhibition itself, intended as an ensemble of multiple images for easy and quick reading, strengthened the message, even through a short, often rushed view.

Figure 1A sample of the flyer that reported some of the events organized by the OGS during the Settimana del Pianeta Terra (Planet Earth Week, https://www.settimanaterra.org, last access: 12 October 2016). The opening of our exhibition titled “Obiettivo Ghiacciai: una bellezza che sta scomparendo” took place on 17 October 2016.

The photographic exhibition, titled “Focus on glaciers” took place in Trieste during October 2016 in the lobby of an early 19th century neoclassical palace, initially the seat of the stock exchange established by Maria Theresa of the House of Habsburg and now the headquarters of the Trieste Chamber of Commerce. The venue was specifically chosen to attract people who cross the lobby daily for work activities. The exhibition was scheduled among the public events foreseen for the Settimana del Pianeta Terra (Planet Earth Week; Fig. 1), a scientific festival spread throughout the Italian territory aiming to promote the geosciences and to increase public awareness of the need to reduce natural risks. The photographs for the exhibition were selected after an OGS internal call for the submission of images focused on glaciers acquired during scientific expeditions and field trips in the polar areas or other relevant regions. Indeed, the OGS researchers and technicians, throughout the years, collected an exceptional treasury of high-quality images. For each photograph, the creators had to provide information about the place, the year and season, the scientific context, and a comment on the motivation, emotional context, and technical details. A committee, formed by geoscientists who were experts in photography and communication skills, selected the images that were most suitable for the exhibition following the principles expressed in Sect. 3. Aesthetic and technical criteria mainly guided the choice of the photographs, but particular attention was also paid to the message that the image could convey to the receiver. The committee received 130 photographs, of which 26 images were chosen for the exhibition, corresponding to approximately 20 % of the original photographic set. The photographs mainly illustrated the two polar regions and the Alps and other mountainous regions. The exhibition was freely accessible to the Chamber of Commerce's visitors and employers and, therefore, to working-age adults (18–64 years). At the exhibition opening, and on the occasion of other conferences related to the Earth Planet public event, the creators of the photographs were present and directly interacted with the public (Fig. 2).

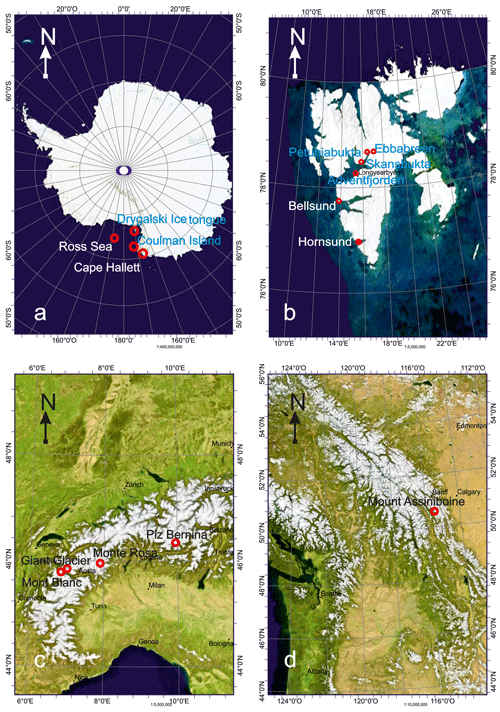

In the following, we present the areas in which the photographs were taken, grouped into two main domains, namely the polar regions and mountain chains (Fig. 3).

Figure 3Maps of the geographical domains in which the pictures from the exhibition were taken. (a) Antarctica, (b) Spitzbergen island in the Svalbard archipelago, (c) the Alpine chain, and (d) the Rocky Mountain chain in Canada. Bright Earth eAtlas base map v1.0 was used for the topography. Credit: AIMS, GBRMPA, JCU, DSITIA, GA, UCSD, NASA, OSM, and ESRI.

4.1 The polar regions

Polar amplification (i.e. the exacerbated effects of climate change at the poles with respect to the rest of the hemisphere) has been well documented within climate change studies through both historical and instrumental observations and model simulations. The causes of this effect are still a matter of discussion (see Stuecker et al., 2019, and reference therein). In Antarctica, the total average ice loss per year was 43 Gt during the 1992–2002 decade, but it sharply accelerated to an average of 220 Gt yr−1 from 2012 to 2017 (Shepherd et al., 2018). The Arctic region is warming even more rapidly; the Svalbard Archipelago, which is located between 74 and 81∘N latitude, has experienced the fastest air temperature increases in the last three decades (Nordli et al., 2014), and climate model projections show that this trend will continue until the end of the 21st century (Førland et al., 2011). Consequently, the accelerated mass loss of the glaciers in western Svalbard implied an increased contribution to the sea level (Kohler et al., 2007; Nuth et al., 2010). In a few years, the Arctic sea ice will disappear during the summer season, opening new commercial and tourist routes through the North Pole; the routes from the Far East to Europe can be shortened by sailing along the Siberian coast instead of via the Suez Canal. Furthermore, easy access to the Arctic Ocean will make the large oil fields of this area very attractive, with the additional potential environmental risks presented by their exploitation. On the other hand, the exceptional melting and retreat of the ice shelf in Ross Bay in Antarctica, documented by OGS researchers in 2018, enabled the acquisition of important information in unexplored areas that were inaccessible during the past years. The white ice coverage in polar areas, either as sea ice or continental ice sheets, helps to regulate the Earth's climate by reflecting most solar energy back to space, whereas the dark oceans and seas absorb most of the solar radiation, further contributing to Earth and climate warming.

Earth's climate warming affects not only ice extension and glaciers but also human lifestyles. In particular, Nordic people, such as the Inuit, risk seeing their livelihoods strongly compromised, and animal species such as polar bears are threatened with extinction (Giovannini and Speroni, 2019). The Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which hosts and protects world seed varieties to prevent accidental loss of diversity, is now in potential danger.

4.1.1 Antarctica

The OGS has continuously developed research in Antarctica since 1988 with funding from the Programma Nazionale di Ricerche in Antartide (PNRA; National Antarctic Research Programme), through the MUR, and within the programmes of the Scientific Committee for Antarctic Research (SCAR). OGS researchers and technicians have developed considerable skills in the geological, geophysical, and biological fields during many geophysical, oceanographic, and/or geological research campaigns in Antarctica with the research vessels (RVs) OGS-Explora, Italica, and other RVs belonging to OGS's international partners. During 2019, OGS acquired the RV Laura Bassi, an icebreaker class (ICE 05 E0) that is managed in cooperation with the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR; National Research Council) and the Agenzia Nazionale per le nuove tecnologie, l'energia e lo sviluppo economico sostenibile (ENEA; National Agency for New Technologies, Energy, and Sustainable Economic Development). Furthermore, the OGS have participated in several onshore international projects in remote field operations at the Italian Mario Zucchelli and Concordia stations; in collaboration with the Argentine Antarctic Institute, it has managed the Antarctic Seismographic Argentinian–Italian Network since 1992 (Russi et al., 2010).

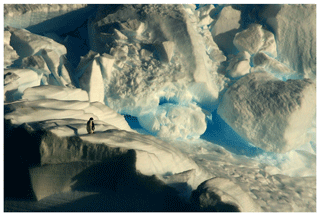

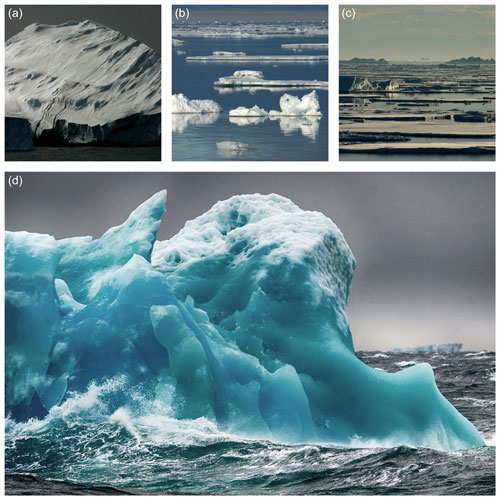

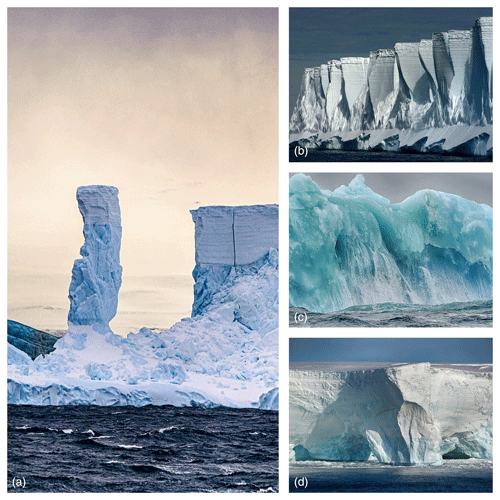

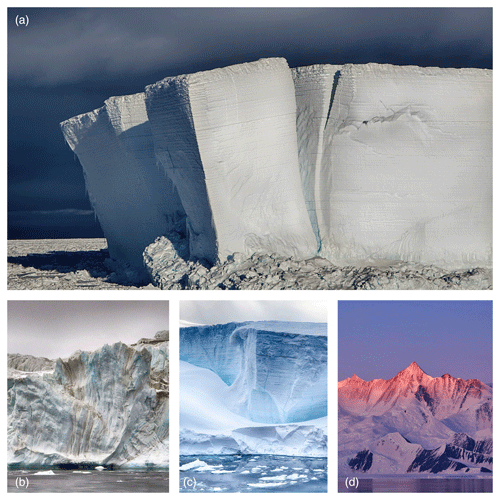

During Antarctic expeditions on research vessels, researchers, technicians, and crew stay on board for approximately 2 months, sharing every moment of life during the data acquisition and convivial breaks. They bring home the feeling of having had a magical experience, despite the often harsh environment and the hard work, together with many photographs of beautiful landscapes crossed during the cruise or the fieldwork. Our exhibition included images from the XXI, XXVIII, XXIX, XXX, and XXXI campaigns to Antarctica (Figs. 3a and 4, 5, 6, and 7). The icebergs, seracs, and cliffs of ice fronts were the main photographic subjects (Figs. 4, 5, and 6), with the alternation of white snow and ice and blue ice generated by the compression of air bubbles incorporated in the ice (Figs. 4a, d, 5, and 6a–c). Figure 7 shows the sole animated subject of the whole exhibition – a lonely, small penguin drifting on an iceberg in the middle of Antarctica.

Figure 4Icebergs in Antarctica. (a) Iceberg from XXI PNRA Antarctic expedition under the Western Antarctic Ice Sheet Evolution (WISE) project. (b, c) Sea ice view during shipping in the Ross Sea during the XXI PNRA Antarctic expedition under the WISE project. (d) Floating blue iceberg in the Ross Sea during the XXVIII PNRA expedition under the palaeomagnetism of sedimentary cores from the Ross Sea outer shelf and continental slope (PNRA-ROSSLOPE II) project.

Figure 5Icebergs and ice tongues in Antarctica. (a) Collapsed iceberg in the Ross Sea during the XXIX PNRA expedition under the ROSSLOPE II project. (b) Iceberg wall in the Ross Sea during the XXI PNRA Antarctic expedition under the WISE project. (c) Floating blue iceberg in the Ross Sea during the XXVIII PNRA expedition under the ROSSLOPE II project. (d) Drygalski glacier tongue in the Ross Sea during the XXXI PNRA expedition under the Holocene climatic fluctuations in sub-millennial recorded in sedimentary sequences expanded the Ross Sea (HOLOFERNE) project.

Figure 6Antarctic landscapes. (a–c) XXVIII PNRA expedition under the ROSSLOPE II project. (a) Iceberg stacked in Cape Hallett in the Ross Sea. (b) Campbell glacier detail in the southwestern Ross Sea. (c) Floating blue iceberg in the Ross Sea. (d) Drygalski glacier tongue in the Ross Sea during the XXXI PNRA expedition under the HOLOFERNE project.

4.1.2 Svalbard islands

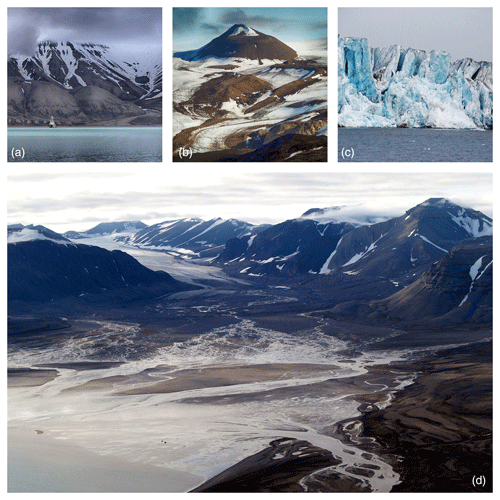

The OGS started its research activity in the Svalbard archipelago in 1971 with an exploratory seismic cruise funded by Norsk Agip (Deluchi, 2013). Since 2001, OGS researchers have been involved in several research cruises (four with the RV OGS-Explora but also with Norwegian, German, and Spanish vessels thanks to the Eurofleets EC-FP7 project) and land-based research within international projects (Fig. 3b), often under the umbrella of the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC). The Svalbard Treaty bans military activities in the Arctic but not research connected to mining or hydrocarbon exploration. This was the case for the Paleokarst research project (Paleokarst Reservoirs: An integrated 3D approach to heterogeneity, reservoir and seismic modelling), jointly funded by industrial partners and the Norwegian Research Council, which aimed to study, with geophysical methods, the structure and physical properties of an onshore site, similar to the reservoirs at depths in the Barents Sea. Within this project, the researchers conducted research while living on a remote camp onshore with views of the mouths of several glaciers (Fig. 8b, d), and they had to apply strategies to prevent polar bear attacks. This project was followed by the Integrated Methods to study PERmafrost characteristics and Variations In an Arctic natural laboratory (Svalbard; IMPERVIA) PNRA project, which was another fieldwork campaign focused on the study of permafrost (Rossi et al., 2018). Other projects developed offshore of the western and southern margin of Svalbard have focused on present and past oceanographic characteristics of the western Spitsbergen Current (the northern branch of the warm North Atlantic oceanic current) and its impact on the dynamics of the paleo-Svalbard–Barents Sea ice sheet for to palaeoclimatic reconstructions. Further research activities targeted the identification of biological oases associated with seepage activities in relation to the presence of gas hydrates developing at the sub-sea floor. In the last two cases, the photos were collected from research vessels during the transfer to different study areas or when sailing back to land after several days or months of on-board activity, often under harsh climatic conditions, rough seas, or being completely blinded by the thick fog or in the winter darkness, with the snow-covered land appearing like a mirage (Figs. 8a, c; 9a, b).

Figure 8Svalbard landscapes in the Svalbard archipelago, Norway. (a) Longyearbyen Bay with tundra landforms during the RV Polarstern expedition PS99-1a under the Eurofleets 2 project of “Bottom currents in a stagnant environment” (BURSTER). (b) A view from the Wordiekammen plateau towards the Ebbabreen, with the Bastion Nunatak, under the Paleokarst project. (c) The front of the Bellsund ice stream in southwestern Svalbard during the RV Ian Mayen 2009 expedition under the University of Tromsø (UiT) “Glaciations in the Barents Sea Area” (GLACIBAR) project. (d) The view from the Wordiekammen plateau towards the Petuniabukta, with the waters from Horbyedalen and Ebbadalen, under the Paleokarst project.

Figure 9Svalbard landscapes. (a) Hornsund fjord, Spitsbergen, during the RV G.O. Sars expedition 191 under the “Present and past flow regime on contourite drifts west of Spitsbergen Area” (PREPARED) Eurofleets 2 project. (b) Ice coverage of the Svalbard islands along the northwestern coast during the RV OGS-Explora expedition under the “Petroleum Assessment of the Arctic North Atlantic and adjacent marine areas” (PANORAMA) project. (c) Skanskbukta bay (on the left), Billefjorden (centre) with (front) Bünsow Land cliffs during the Poli Arctici Skanskbukta base camp field trip by the Northern Rangers group.

In a field camp in Skanskbukta bay (Figs. 3b, 9c), with the base camp encircled by breath-taking mountains, small waterfalls and creeks, the OGS researchers witnessed several huts as vivid memories of human activities at the beginning of the last century.

4.2 Mountain chains: the Alps and the Rocky Mountains

During 2019, for the first time, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a report on the present impacts of climate change on the world's mountain environments. The surface air temperatures in the mountains of western North America, the European Alps, and high mountain Asia increased at an average rate of 0.3 ∘C per decade during the last 30 years, therefore outpacing the global warming rate (IPCC, 2019). The snow coverage duration, thickness, and extent decreased by an average of 5 d per decade, especially for those at lower elevations. From 2006 to 2015, the mass change in the glaciers in most of the mountain regions, excluding the polar areas (Canadian and Russian Arctic, Svalbard, Greenland, and Antarctica) was approximately kg m−2 yr−1. The regionally averaged mass budgets were mostly negative (less than −850 kg m−2 yr−1) in the southern Andes, Caucasus, and central Europe and least negative in high mountain Asia ( kg m−2 yr−1). Sparse and unevenly distributed measurements have shown a progressive increase in the permafrost temperature, with a shift of 0.19±0.05 ∘C on average for approximately 28 locations in the European Alps, Scandinavia, Canada, and Asia during the past decade.

4.2.1 The Alps

Between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 21st centuries, the average air temperature on the Alps rose by approximately 2 ∘C, i.e. more than twice the temperature increase observed throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Over the same period, the rainfall mass recorded an increasing trend in the northern part of the Alps and a decreasing trend in the southern sector.

Since the end of the Little Ice Age (LIA; ca. 1850 in Europe), a general retreat of the glaciers in the Alps has occurred, although it was locally interrupted by two short-lived phases of re-advance which occurred during the 1920s and 1970s. However, it has been estimated that the glacial area in the Alps has been severely reduced by approximately half since the end of LIA, and that the rate of reduction has considerably accelerated since the 1980s, especially on the southern side of the chain.

According to the last cadastre of the Italian glaciers (Smiraglia and Diolaiuti, 2015) over as few as the last 50 years, the total area has decreased from 527 to 368 km2, leading to the extinction of 180 glaciers. Nigrelli et al. (2015) related the recent glacial shrinking to the climatic variations documented by the meteorological stations, providing an accurate picture of the rapid regression of the glaciers and quantifying the relationship between climate and glaciers.

However, we can hypothesize that, at least in some cases, the combined action of the temperature increase and precipitation decrease that occurred after 1980 influenced the evolution of glaciers. According to the present rate of glacier decline, and according to the observed climatic warming trends, the glaciers in the Italian Alps are expected to disappear by 2050 (Santin et al., 2019).

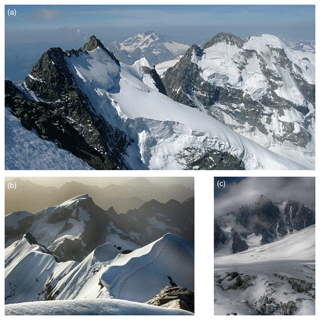

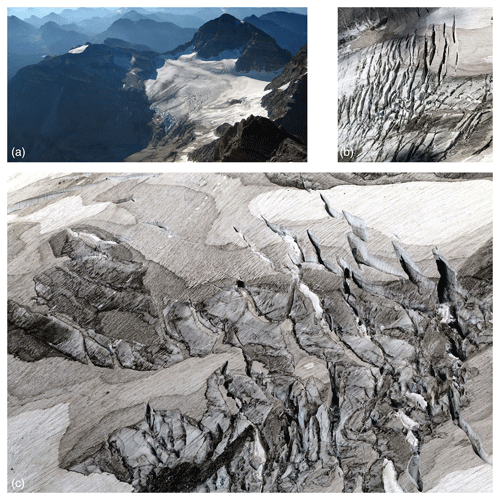

In the frame of the PNRA project of Subglacial lake exploration in the Whillans Ice Stream region (West Antarctica; WISSLAKE, the OGS researchers performed geophysical tests on Alpine glaciers to evaluate the feasibility of the applied methods in quantifying the glacier thickness and structure (Fig. 10; Picotti et al., 2017). The geophysical methods have been used on the glaciers of the Adamello and Ortles-Cevedale (Ortler Alps) massifs (Italy), the Bernese Oberland Alps (Switzerland), and on the Whillans Ice Stream (western Antarctica). Many sites were inspected along the Alpine chain to find suitable sites for the application of such techniques. The retreating glaciers bared their surface structure and crevasses, creating fascinating graphic effects (examples from Mont Blanc; Fig. 11b, c).

Figure 10Mountain landscapes. (a) Piz Bernina (Italy). The PNRA–WISSLAKE project, including (b) Monte Rosa (Italy) and the (c) Géant Glacier of Mont Blanc (Italy).

Figure 11(a) A glacier on Mount Assiniboine, British Columbia, Canada seen during a field trip in the framework of the SEG 2009 Summer Research Workshop on “CO2 Sequestration Geophysics”. (b, c) A minor glacier in the Mont Blanc group (Italy) seen during a field trip in the frame of the “Near Surface Geoscience 2015 – 21st European Meeting of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics” project.

4.2.2 Canada

The annual and seasonal average temperatures across Canada increased during recent decades, with the most significant warming occurring during the winter seasons. In particular, from 1948 to 2016 northern Canada recorded an increase of 2.3 ∘C compared to the 1.7 ∘C for the whole country.

Unlike the Alps, in Canada the precipitation averaged over the country has increased by approximately 20 % from 1948 to 2012 (Vincent et al., 2015). Nevertheless, during 2007, the glaciers' volume loss was estimated to be as much as 22.48±5.53 km3 yr−1, but such a high rate has recently accelerated further. A glacier such as the Peyto Glacier, which is in the Rocky Mountains and part of Banff National Park, has lost approximately 70 % of its mass in the past 50 years. OGS researchers also performed site inspections in Banff National Park to further test the geophysical methods applied to the studying and monitoring of glacier retreat around the world (Fig. 11a).

The OGS exhibition titled “Focus on glaciers” used the beauty of the images and the impression of majesty and peace that the glaciers can inspire in visitors to transmit the message of environmental fragility and the need for its protection. In recent years, the OGS has already participated in photographic exhibitions of research activities (e.g. European Researchers' Night in Trieste in 2013; 30 years of the Italian research programme in Antarctica in Rome in 2015), but the “Focus on glaciers” exhibition was the first attempt by the OGS to use research photography to animate people on climate change themes. The creators of the photographs are research scientists involved in offshore and inland scientific activities and effective actors in artistic production, showing the means by which art and science can work together (Malina, 2010), even if they are not professional photographers. The message that some prompt actions can still help to reduce the climate crisis was conveyed through the emotion that arose at the sight of single, high-quality images representing the vanishing beauty of glaciers.

As our exhibition was an a posteriori collection of photographs taken during short-term scientific offshore expeditions or inland campaigns, and almost never in the same place, it was not possible to document the temporal transformation of the studied areas as a consequence of climate warming. However, we deemed the large number of photographs as worthy witnesses to the magnificence and grandeur of a fragile landscape that is in danger of extinction. The criteria of a high technical quality and a strong emotional impact drove the selection of the images. This choice was aimed at obtaining a fast and immediate perception of the message by the receiver. This was the case for the collapsed icebergs (Figs. 5a, d; 6a), the blue ice floating in the rough sea (Fig. 4d), or the lonely penguin on a drifting iceberg (Fig. 7) as being an emblematic symbol of the living species in danger of extinction due to the climate crisis. Figure 8d and the graphic effects transmitted by Fig. 11b and c dramatically document glacier melting and the possible desolation of the future landscape. The contemplation of the 26 photographs as a whole produced a strengthening of the message that the viewer could perceive, even from a fleeting passage through a public, crowded place. Therefore, the exhibition became the way to bring scientists closer to the public, specifically considering working-age adults (18–64 years), in an environment typically unrelated to science. The location of the lobby of the Chamber of Commerce of Trieste appeared to be an excellent choice because approximately 100 people crossed the location for business purposes every day, so we could easily quantify an engaged audience of approximately 2000 people from different social classes, cultural levels, and nationalities. Moreover, during the opening of the exhibition, and on the occasion of some other conferences related to the Earth Planet public event, approximately 250 people had the unique opportunity to interact directly with the creators of the photographs. The most common question asked addressed the modality of the ongoing climate changes and the immediate impact on the present lifestyle of humans. The creators had the duty to calibrate their answers in order to convey a simple but strong message without the use of complicated scientific or technical language or, especially, without making people feel powerless regarding taking action on or the mitigation of the climate crisis. In contrast, the very important message to convey was the necessity of acting fast and the possibility of success. Vivid conversations occurred near the panels hosting the photographs, and the visitors were delighted to satisfy their curiosity on either the technical aspects of the research, the development of the climate change studies, and/or the context in which the geoscientists took the photographs or about more technical photographic details such as the camera exposure, the possible postprocessing work, or aesthetic choices. Surprisingly, some technical questions regarded not only the topic of climate change but also the geology of polar areas and the geomorphology of glaciers, adding further scientific value to the artistic quality of the images.

The feedback received on the exposition accomplished Dahlstrom's (2014) recommendations and confirmed the observations made by Lacchia et al. (2020) about the importance of including emotional or challenging aspects during science communications, such as research motivation or descriptions related to logistics, routine duties, and lifestyle in extreme contexts. We believe that the choice of showing images of environments closer to our heritage, such as the Alps, assisted the researchers in their delicate and difficult attempt to transmit the message that the climate crisis is a real problem affecting all of us and that each small contribution from everybody can make a difference. The slow but inexorable vanishing of glaciers is striking evidence that global warming is effectively occurring here and now, and it will probably deeply affect the way our entire society will act in the future. Global warming is an entity of such vast temporal and spatial dimensions that is so interconnected with human activity that it seems to defy not only our control but also our understanding. Our concept of the world and the environment must change to allow new awareness and to promote a sustainable and respectful coexistence between humanity and nature. Communication activities, such as the “Focus on glaciers” exhibition, and other outreach actions promoted by OGS and other institutions, are critical for highlighting the problem and making it relevant to the general public. The debate about climate change communication strategies is still active, and catastrophic frames are controversial (König and Jucks, 2019).

The exhibition project is still active. The pictures are presently displayed on OGS premises, and our colleagues are strongly encouraged to collect new images during their scientific expeditions to upgrade the exhibition. This experience may be further stimulated within the research community to keep track of and record the rapid changes occurring in the Earth's glaciers. The exhibition “Focus on glaciers” can be considered as being the first event, for the OGS, with a new way of communicating the themes of climate change or other themes of utmost importance for our society. Researchers can develop alternative topics on the basis of the pictures collected during routine work that can be displayed through similar future exhibitions. Moreover, by adding multimedia support that shows snapshots of life during fieldwork or episodes related to the scientific campaigns would be of importance in terms of catching the visitors' attention and communicating more effectively. In the course of future events, we will further involve visitors through short surveys to verify whether the transmitted message was easily accessible and what level of awareness was obtained after visiting the exhibition.

No data sets were used in this article.

GR, GB, and AS conceived the idea of the exhibition and wrote the paper. RGL, SP, and SS read the paper and provided comments and corrections for improvements. DC and GR created the maps in Fig. 3. GR and AS composed all the other figures in the paper. GR, GB, DC, LF, RGL, MEM, SP, and SS provided the images selected for the exhibition. PG and FP curated the installation of the exhibition and the advertising of the event.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

This article is part of the special issue “Five years of Earth sciences and art at the EGU (2015–2019)”. It is a result of the EGU General Assembly 2016, Vienna, Austria, 17–22 April 2016.

We warmly thank all the colleagues who sent us photos from their expeditions to glaciers and polar areas. We are grateful to the Camera di Commercio, Industria, Artigianato e Agricoltura Venezia Giulia for hosting the exhibition at its premises.

We are indebted to Mariele Neudecker, an anonymous referee, and the editor, Francesco Mugnai, for their constructive and stimulating comments, which led to significant improvement of this paper.

This research has been supported by Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia (project “Diverso - Divulgazione e ricerca per un futuro sostenibile”).

This paper was edited by Francesco Mugnai and reviewed by Mariele Neudecker and one anonymous referee.

Balog, J.: Ice: Portraits of Vanishing Glaciers, Rizzoli, New York, 288 pp., 2012.

Balog, J.: Extreme Ice Survey – A program of Earth Vision Institute, available at: http://extremeicesurvey.org/ (last access: 2 September 2020), 2019.

Berlo, D.: The process of communication, Rinehart & Winston, New York, 1960.

Chasing Ice: Chasing Ice – 2014 Emmy® Award Winner, available at: https://chasingice.com/, last access: 2 September 2020.

Cook, J., Oreskes, N., Doran, P. T., Anderegg, W. R. L., Verheggen, B., Maibach, E. W., Carlton, J. S., Lewandowskym, S., Skuce, A. G., and Green, S. A.: Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming, Environ. Res. Lett., 11, 048002, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002, 2016.

Dahlstrom, M. F.: Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, 13614–13620, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320645111, 2014.

Deluchi, L.: 1971, Norsk Agip's seismic survey of the Svalbard region, available at: http://www.pionierieni.it/wp/wp-content/uploads/Norsk-Agip-1971-Seismic-survey-of-the-Svalbard-region.pdf (last access: 31 August 2020), 2013.

EGU: Imaggeo. The geosciences image and video repository of the European Geosciences Union, available at: https://imaggeo.egu.eu/ (last access: 15 February 2020), 2019.

Førland, E. J., Benestad, R., Hanssen-Bauer, I., Haugen, J. E., and Skaugen, T. E.: Temperature and precipitation development at Svalbard 1900–2100, Adv. Meteorol., 2011, 893790, https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/893790, 2011.

Giovannini, E. and Speroni, D.: Un mondo sostenibile in 100 foto, Bari-Roma, Laterza, 2019.

Kohler, J., James, T. D., Murray, T., Nuth, C., Brandt, O., Barrand, N. E., Aas, H. F., and Luckman, A.: Acceleration in thinning rate on western Svalbard glaciers, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L18502, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL030681, 2007.

König, L. and Jucks, R.: Hot topics in science communication: Aggressive language decreases trustworthiness and credibility in scientific debates, Public Underst. Sci., 28, 401–416, 2019.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., and Midgley, P. M., Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp., https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324, 2013.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC), Chapter 2: High Mountain Areas, IPCC Monaco, 2019, available at: https://report.ipcc.ch/srocc/pdf/SROCC_FinalDraft_Chapter2.pdf (last access: 14 February 2020), 2019.

Lacchia, A., Schuitema, G., and McAuliffe, F.: The human side of geoscientists: comparing geoscientists' and non-geoscientists' cognitive and affective responses to geology, Geosci. Commun., 3, 291–302, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-3-291-2020, 2020.

Liverman, D. G. E.: Environmental geoscience; communication challenges, Geological Society, London Special Publications, 305, 197–209, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP305.17, 2008.

Macromicro non profit Association: On the trail of the glaciers, available at: https://onthetrailoftheglaciers.com/, last access: 13 February 2020.

Malina, R.: What are the different types of art science collaboration, available at: http://malina.diatrope.com/2010/08/29/what-are-the-different-types-of-art-science-collaboration/ (last access: 17 November 2020), 2010.

National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC): Advancing knowledge of Earth's frozen regions, available at: https://nsidc.org/, last access: 14 February 2020.

Neudecker, M. and Project Pressure Partnership: Project Pressure, available at: https://www.project-pressure.org/mariele-neudecker-and-project-pressure-partnership/ (last access: 2 September 2020), 2015.

Nordli, O., Przybylak, R., Ogilvie, A. E. J., and Isaksen, K.: Long-term temperature trends and variability on Spitsbergen: the extended Svalbard Airport temperature series, Polar Res., 33, 21349, https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v33.21349, 2014.

Nigrelli, G., Lucchesi, S., Bertotto, S., Fioraso, G., and Chiarle, M.: Climate variability and Alpine glaciers evolution in Northwestern Italy from the Little Ice Age to the 2010s, Theor. Appl. Climatol., 122, 595–608, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-014-1313-x, 2015.

Nuth, C., Moholdt, G., Kohler, J., Hagen, J. O., and Kääb, A.: Svalbard glacier elevation changes and contribution to sea level rise, J. Geophys. Res., 115, F01008, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JF001223, 2010.

Picotti, S., Francese, R., Giorgi, M., Pettenati, F., and Carcione, J. M.: Estimation of glaciers thicknesses and basal properties using the horizontal-to-vertical component spectral ratio (HVSR) technique from passive seismic data, J. Glaciol., 63, 229–248, https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2016.135, 2017.

Rossi, G., Accaino, F., Boaga, J., Petronio, L., Romeo, R., and Wheeler, W.: Seismic survey on an open Pingo system in Adventdalen Valley, Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Near Surf. Geophys., 16, 89–103, https://doi.org/10.3997/1873-0604.2017037, 2018.

Russi, M., Febrer, J. M., and Plasencia Linares, M. P.: The Antarctic Seismographic Argentinean-Italian Network: technical development and scientific research from 1992 to 2009, Bolletino di Geofisica Teorica ed Applicata, 51, 23–41, 2010.

Santin, I., Colucci, R. R., Žebre, M., Pavan, M., Cagnati, A., and Forte, E.: Recent evolution of Marmolada glacier (Dolomites, Italy) by means of ground and airborne GPR surveys, Remote Sens. Environ., 235, 111442, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111442, 2019.

Shannon, C.: A Mathematical Theory of Communication, Bell Syst. Tech. J., 27, 379–423, https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x, 1948.

Shepherd, A., Ivins, E., Rignot, E., et al. (The IMBIE team): Mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2017, Nature, 558, 219–222, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0179-y, 2018.

Shepherd, A., Ivins, E., Rignot, E., et al. (The IMBIE team): Mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2018, Nature, 579, 233–239, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1855-2, 2020.

Smiraglia, C. and Diolaiuti, G. (Eds.): Il Nuovo Catasto dei Ghiacciai Italiani, EvK2CNR (Ed.), Bergamo, 400 pp., 2015.

Stone, K.: Photography: Art or Science?, Project RAWcast, available at: https://projectrawcast.com/photography-art-or-science/ (last access: 13 February 2020), 2017.

Stuecker, M. F., Bitz, C. M., Armour, K. C., Proistosescu, C., Kang, S. M., Xie, S. P., Kim, D., McGregor, S., Zhang, W. J., and Taylor, M.: US philanthropists vow to raise millions for climate activists, The Guardian, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jul/12/us-philanthropists-vow-to-raise-millions-for-climate-activists (last access: 17 November 2020), 12 July 2019.

UN (United Nations): Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1, 41 pp., 2015.

USGS Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center: Repeat Photography Project, available at: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/norock/science/repeat-photography-project?qt-science_center_objects=&qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects (last access: 11 November 2020), 2019.

Vincent, L. A., Zhang, X., Brown, R. D., Feng, Y., Mekis, E., Milewska, E. J., Wan, H., and Wang, X. L.: Observed trends in Canada's climate and influence of low-frequency variability modes, J. Climate, 28, 4545–4560, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00697.1, 2015.