the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Science, art, and legends in geotourism: a multidisciplinary geotrail approach in Alagna Valsesia, Sesia Val Grande Geopark (NW Italy)

Michele Guerini

Alice Ferrazza

Gianluca D'Incà Levis

This paper presents the results of a project based on a method that integrates geological knowledge and local cultural heritage within the Alagna Valsesia area, located in the Sesia Val Grande Geopark, Italy. Through a multidisciplinary, co-creative approach an artist's book was realised serving both as a guide to the geotrail and a communicative tool for broader educational outreach. Thanks to the engagement of members of the local Walser community and the cooperation of artists from Dolomiticontemporanee collective, the project blended geoscientific communication with locally rooted storytelling to enhance understanding of the geological and cultural landscapes of the area. The artist's book combines scientific accuracy with vernacular insights gathered during the co-creation process, covering significant observation points that narrate geological phenomena and the legacy of the Walser people. The new artist's book represents an innovative way to communicate geoscience providing a valuable tool for visitors, educational institutions, and the local community, promoting conservation awareness through an immersive, narrative-driven experience. The method presented in this study is applicable in other settings and is particularly suitable for geopark areas, as it offers a new way of communicating geological heritage by integrating the work of geoscientists, artists and local communities. Moreover, this new strategy avoids the logistical obstacles associated with physical educational displays in mountainous terrains and underlines the benefits of accessible, multi-platform geoscientific engagement.

- Article

(5033 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(8667 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Geotourism is a form of tourism driven by the curiosity to understand how landscapes have been shaped and the geological history behind their formation. As indicated in the Arouca Declaration (https://www.europeangeoparks.org/?p=223, last access: 20 November 2025), it can serve as a tool to conserve and disseminate the history of Life on Earth, fostering a deeper appreciation and awareness of the environment, and supporting sustainable territorial development (Newsome and Dowling, 2010; Hose, 2016; Gordon, 2018). Developing geotourism opportunities may enhance both the visitors' and locals' experience increasing the awareness of geoheritage through the geoeducation, and promoting geoconservation (Farsani et al., 2011; AbdelMaksoud et al., 2021; Coratza et al., 2023). In practice, this often involves the use of classical interpretation tools, such as information panels and guides, that highlight the geological significance of particular sites, designated as geosites. Moreover, among geotourism initiatives it is possible to find the geotrails, which are designed to connect visitors to multiple geosites, guiding them through the landscape and telling its geological story (Hose, 2020). While there have been attempts in the literature to provide guidelines on how to construct and evaluate effective panels (Martin et al., 2010; Coratza et al., 2023), these have largely focused on the scientific and didactic content, with less attention paid to the communicative effectiveness of such tools. Such an approach may lead to the creation of interpretation tools that contain valuable scientific and didactic content, but which fail to capture the interest of the local population and visitors (Macadam, 2018). Nevertheless, geotouristic initiatives should encourage geoscientists to effectively communicate earth sciences, translating their technical knowledge for a general, non-specialist audience, especially in light of increasing geoenvironmental challenges.

Geoscience communication is still an emerging discipline (Illingworth et al., 2018), and it has progressed at a slower pace compared to the more thoroughly researched field of science communication (Weigold, 2001; Trench et al., 2014). For this reason, there remains a paucity of studies that assess the effectiveness of efforts in communication of scientists within geoscience (Wijnen et al., 2024). Additionally, many of these communication activities are developed based on empirical practices, often designed based on assumptions of a knowledge gap within the public (Rodrigues et al., 2023). However, effective communication is increasingly understood as a two-way interaction, where knowledge is not simply transmitted to the public, but is exchanged through dialogue about scientific topics that impact their lives (Stewart and Lewis, 2017). This reflection has enabled geoscience to adopt more dialogical approaches to the public(s) it seeks to engage with, also paving the way for a multidisciplinary approach. Indeed, in recent years, a growing number of studies has tested the integration of geoscience with creative elements such as art (Valentini et al., 2022), poetry (Illingworth and Jack, 2018; Nesci and Valentini, 2020; Flint, 2024), (video)games (Locritani et al., 2020), comics (Wings et al., 2023), and music (Nesci and Valentini, 2020), demonstrating how these elements facilitate both the ability to communicate complex issues to a non-expert audience and the ability to engage this audience generating dialogue between scientists and nonscientists (Nisbet et al., 2010; Stewart and Lewis, 2017; Illingworth, 2020). Our study aligns with and builds upon such research, combining scientific communication with artistic elements (illustrations and narrative). The aim is to showcase the informational richness in both cultural and geological sense of landscapes to a broader audience. At the same time, it suggests the potential efficacy of a methodology that engages the local community in a process of co-creation, intended as a collaborative process that enables local stakeholders and communities to participate directly in the decision process, developing more inclusive and sustainable paths for change (Gunnell et al., 2021), to define the elements to be communicated in order to attract visitors to know and experience these places.

The value of co-creation approaches arises from the growing complexity of real-world problems and contemporary social challenges, meaning that meaningful solutions can only be developed effectively by integrating inclusive methods like co-creation (Senabre Hidalgo et al., 2021). In this manner, geoscientists can learn more about the vision of local communities, treated as equals and not just as people to whom knowledge can be transmitted. Indeed, a non-hierarchical approach can facilitate effective dialogue, encouraging the public to contribute their knowledge and experience (Illingworth, 2023). This approach can provide new perspectives, such as a better chance of project success, a stronger sense of belonging for the local community, and the possibility of using local knowledge (Rock et al., 2018; van Beveren et al., 2022). The use of local knowledge and practices from communities, also known as “vernacular culture”, can enhance the understanding of how human activities and structures interact with natural ecosystems. A site-specific understanding of the relationship between the built and natural environment can play a critical role in better addressing the challenges of climate change and promoting effective strategies for adapting to its impacts (Hu et al., 2023). Ultimately, this integration supports sustainable development in the region by promoting resilience and environmental management.

Such a method can be particularly effective in geoheritage communication. Geoheritage, using geosites, can link geoscience and society offering a wide range of opportunities to use new communication approaches that allow science to reach a wider audience and to use new interpretation tools (Tormey, 2019; Shajahan et al., 2024). Thus, it would also be possible to promote territories through the fostering of conscious tourism (Higuchi and Yamanaka, 2017). Following this rationale and in accordance with the UNESCO definition (https://www.unesco.org/en/iggp/geoparks/about, last access: 20 November 2025), geoparks appear to have the chance to become the ideal place to develop co-creation projects, which would then result in geotouristic offers characterized by a new method of communication. In fact, geoparks can be considered as places of special geological value, but also as open-air laboratories where projects can be developed that lead to the protection of the territory in a holistic sense.

In this paper, we present a methodology implemented in Alagna Valsesia area, located in the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (Italy) to conceive a participatory geotrail which, through a multidisciplinary approach, integrates co-creation and artistic elements with geoscientific communication.

The objective of this work was to stimulate a new perception of the landscape to the largest possible audience, starting from its aesthetic value and ultimately leading to a deeper understanding of its geological history, relation with local communities, environmental challenges, and vulnerabilities, all of which have participated in shaping the actual status.

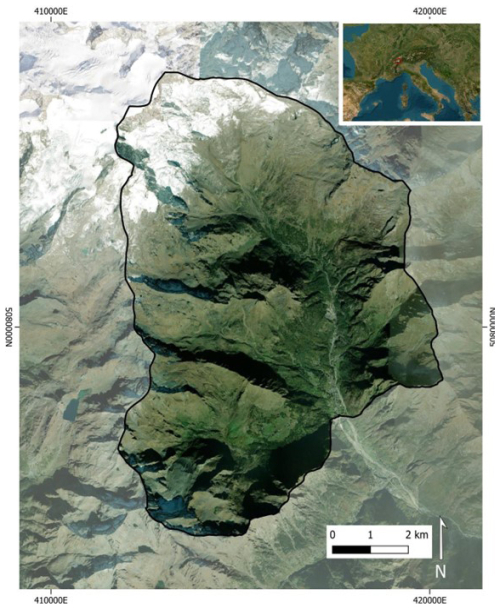

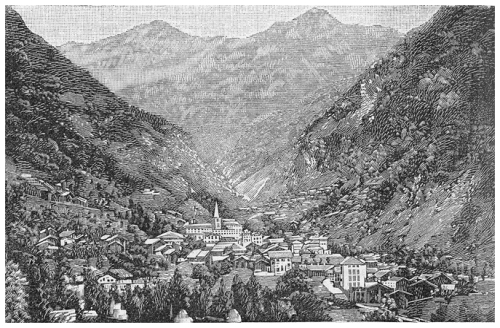

Figure 1Ancient xylography of Alagna Valsesia. Image by Wikimedia Commons (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/Alagna_%28xilografia%29.jpg/640px-Alagna_%28xilografia%29.jpg, last access: 21 June 2025).

Alagna Valsesia is a mountainous area located in the upper Sesia Valley at the foot of Mount Rose in the Piedmont Region and lies within the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (Figs. 1 and 2). It has been the focus of various studies for its relevance in both geology, tourism, and culture. Its position between the Austroalpine and Pennine domains offers valuable insights into both continental and oceanic crust formations, making it significant for studying the Alpine orogenesis (Piana et al., 2017). Moreover, it is a significant tourist destination within the geopark, attracting visitors mostly during the winter season, and hosting the Walser, a local community that migrated from the canton of Valais (Wallis, located in present-day Switzerland) during the Middle Ages to escape from the population pressure in Upper Valais and to find new farmlands (Wanner, 1995; Rizzi and Gianoglio, 2023). The Walser are known for their climate resilience and for preserving centuries-old traditions that continue to shape the region's cultural landscape (Rizzi and Gianoglio, 2023).

Designing a geotrail in Alagna Valsesia, already a well-established tourist destination, means giving visitors the opportunity to better understand the geological and geomorphological processes that shaped the landscape. Through this deeper understanding and effective communication, the public can develop a more meaningful connection to the region and fully appreciate it. Furthermore, the geotrail has an educational value and requires an effective narrative to guide visitors.

Consequently, another goal of the work is to define a communication strategy developed in collaboration with representatives of the local community through a co-creation process and integrated with the work of artists.

The whole project took place thanks to PhD research, initiated in 2022, aimed at fostering the geotourism opportunities in Alagna Valsesia, disseminating the Geoheritage through a multidisciplinary approach (Guerini, 2025). It was conducted in collaboration with key partners, including the Dolomiticontemporanee project (DC), the Sesia Val Grande Geopark, and the Alagna municipality. These organizations share a common interest in promoting deeper public awareness of the landscape while involving the local community in the process. We initially presented the idea of a participatory geotrail at national and international level in several conferences (e.g. Guerini et al., 2024a). Then, to effectively communicate this to the public, we collaborated with our partners to offer to the public different products, the most important of which is a booklet guide of the geotrail, that adopted a multidisciplinary communication strategy that combines three key forms of expression: science, visual art, and narrative (Guerini, 2025, cf. Annex; see Supplement). The following sections outline the method used to design the geotrail, incorporate local knowledge through co-creation, and engage artists to enrich the project's visual storytelling.

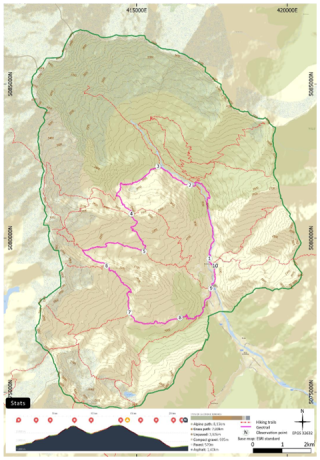

3.1 Geotrail route definition

In developing the geotrail design for Alagna Valsesia, we first conducted an in-depth assessment of the environmental context of the region from a geological perspective. This involved the assessment of the geodiversity of the area and, among the geodiversity elements, the recognition of the sites that hold significant geological heritage, following the framework that has been established in previous studies (Guerini et al., 2024b). Secondly, we carefully designed the geotrail to highlight these geosites and present them in a coherent narrative, showcasing the rich geological, geomorphological, and cultural heritage of Alagna Valsesia. Integrating geosites with cultural sites in geopark strategies has proven effective in fostering a comprehensive appreciation and protection of the landscape (Guerini et al., 2023). The resulting geotrail is approximately 22 km long, mostly on easy hiking trails, in an elevation range of 1200 to 2450 with an elevation gain of 1700 m, offering a comprehensive, immersive experience into the landscape (Fig. 3). This trail highlights the region's geological significance through 25 geosites, illustrating the value of geodiversity for local communities and ecosystems, as well as its vulnerability to climate change. It also reveals how the Walser community has interacted with and adapted to this unique environment over centuries. Given its length and diversity, the trail is well suited for a two-day journey, promoting slow tourism and a more immersive connection with the area, supporting more sustainable geotourism by encouraging deeper engagement with the landscape (Widawski and Oleśniewicz, 2019). The trail also includes four mountain huts (Fig. 4), where visitors can rest, enjoy regional cuisine, and purchase local products, enriching their connection to Alagna's cultural landscape. By encouraging longer stays and deeper engagement with local heritage and services, slow tourism benefits both visitors and the local economy (Wheeler, 1995). For visitors who prefer a briefer journey, alternative routes are available that do not include all the viewpoints and conclude the circuit of the trail in advance. However, these routes could offer a less comprehensive experience of the trail's themes.

Figure 3Design of the geotrail in Alagna Valsesia with statistics, including the altimetry and the different type of surfaces. Source of the basemap: ESRI | Powered by ESRI. Altimetry by © Komoot.

Figure 4Example of an alpine hut: this is the hut in the Bors valley, the second to be encountered along the geotrail route. Photo by the authors.

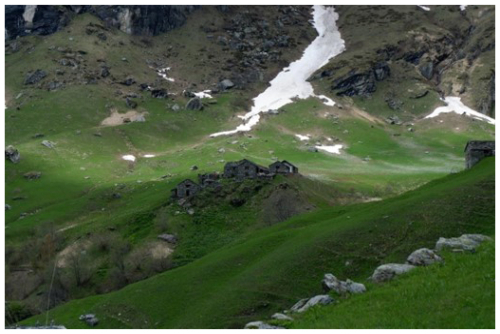

Finally, the trail passes through four distinct geological units, emphasizing the geologic diversity of the region. Developed with valuable input from the Walser community, it also passes through four alpine pastures and over ten traditional Walser villages (Fig. 5), acknowledging and enhancing Walser heritage while integrating cultural and natural values into a unified narrative.

3.2 Co-creation and unstructured interview

We initially mapped the geotrail with a scientific focus to highlight the area's geological and cultural heritage, central to the geotourism experience. Its aim is to convey the region's geological history while illustrating local customs and their interaction with the environment, offering visitors a holistic interpretation of the territory's complexity and layered history, and serving as a valuable tool for geoeducation. For this, after the design phase, we focused on a strategy to effectively communicate these multifaceted elements to a diverse audience. In particular, It aimed at emphasizes the region's geological beauty alongside local culture and Walser traditions, using vernacular knowledge as the narrative foundation, while also addressing the real challenges faced by the community. Following the latest results on the geoscience communication effectiveness (Loroño-Leturiondo et al., 2019; Wibeck et al., 2022) we adopted a co-creation strategy with the Walser local community to favour an equitable exchange, thus avoiding perceiving citizens as individuals with a deficit in knowledge (Harris et al., 2021). The objectives were to collect memories of Walser customs and traditions; collect the stories of Walser oral culture; to identify the principal challenges facing the Alagna Valsesia area; and to understand how to utilize and communicate this vernacular knowledge within the geotrail.

To achieve this, we firstly contacted by email the local stakeholders, such as the Walser culture centers and the municipality. Then, we physically spent a whole month in the study area to foster the potential dialogue with the locals. Two-way communication can take many forms, but for the purpose of our study we preferred the face-to-face dialogues with locals, because this form effectively enables participants and researchers to bridge the gap in their understanding that often exists between them (Rangecroft et al., 2024). Particularly, we engaged members of the local community according to specific criteria:

-

Representatives from Walser cultural centres and individuals knowledgeable in Walser traditions;

-

Descendants of the Walser people;

-

Residents and professionals in Alagna Valsesia who actively contribute to environmental conservation or cultural preservation.

This approach enabled us to gain insight into the local community and engage in informal discourse, which we documented through taking notes (Zhang and Wildemuth, 2017). Specifically, we presented each member of the local community with a trail map and elucidated the objective of our project, then we made the unstructured interview.

This approach proved to enhance practicality in diverse organizational contexts and spontaneous dialogue that was both voluntary (each participant gave verbal consent) and comfortable for members of the local community, without the constraints of a larger group (Chauhan, 2022). The principal outcomes of these dialogues were:

-

The identification of key elements of the Walser community to be enhanced. There was considerable discussion of the vernacular architecture and villages and pastures of the Otro Valley (Fig. 6). Other elements that emerged as significant were traditional clothing and festivals, including the bread festival and a procession known as the “Flowered Rosary” (Fig. 7);

-

The ancient oral traditions (with legends and tales) and the vernacular knowledge were identified as a valuable resource for geotrail storytelling. This also resulted in the consultation of local and national bibliography, in which numerous legends are collected (Sibilla, 1980; Savi-Lopez, 1993; Wanner, 1995; Christillin et al., 2010);

-

The setting of some of these legends in the Alagna area and the integration of these with scientific knowledge. This emphasized a close relationship between the Walser community and high-altitude environments, as well as a connection with ice and glaciers;

-

A discussion regarding the current issues facing Alagna. At this stage, problems such as juvenile emigration (also a recurring element in Walser history), coexistence with wild animals, the protection of protected species, and the challenge of climate change for the Walser way of life emerged.

Figure 6Typical Walser house, an example of vernacular architecture in Alagna Valsesia. Photo by the authors.

Figure 7The picture shows a moment of the bread festival, an ancient Walser tradition in which bread was baked to meet the needs of the whole community throughout the winter. Photo by Federico Bierti.

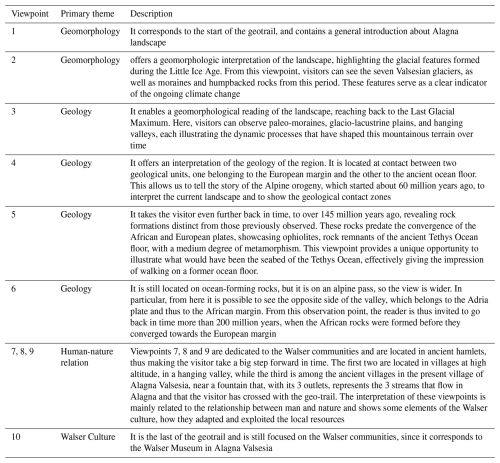

To enhance the interpretive experience, we selected ten observation points, each positioned to provide optimal views of notable geological formations and to incorporate vernacular knowledge. These geostops serve not only as points to observe geosites but also as focal points for interpreting the wider landscape (da Silva et al., 2020). Here, visitors will have access to interpretive elements that will guide them along the way.

At this stage, we didn't ask to the Walser community members to merge their legends with geological knowledge. The co-creation process focused on sharing knowledge and deciding which elements to prioritize in communication, taking into account practical barriers: creative methods require significant time and familiarity, and participants are not always comfortable engaging in them (Van Loon et al., 2020). Therefore, in the final phase we adopted a creative approach through a multidisciplinary team that included artists. Their role was twofold: to reinterpret existing Walser legends in a contemporary style addressing current local issues, and to produce images and illustrations that enhanced the elements identified during co-creation.

3.3 Artistic collaboration

The integration of artistic collaboration into the design and communication of the geotrail in Alagna Valsesia represents a new approach to the elaboration of data gathered during the co-creation process. This phase of the project was conducted in collaboration with DC (https://www.dolomiticontemporanee.net/, last access: 7 May 2025), that could be defined as a cultural association whose aim is to perform the project of art, networks, science, integrations between parts, that combines contemporary art and cultural practices to reactivate spaces with unused potential (dolomiti contemporanee, 2024). The geoscientists were hosted by DC through a residency and contagion process in the Dolomites, where DC has been active since 2011. In a context where the mountain is often represented in a comedic manner through cultivated stereotypes that correspond to aesthetic and psychological ready-mades, which serve to sell it to tourists, DC works to construct an intelligent, critical, and proactive idea of mountains (D'Incà Levis, 2016). It is imperative that the mountain be safeguarded in terms of its environmental value, while simultaneously encouraging the advancement of its cultural identity (Chan et al., 2016). Consequently, DC regards the mountain as a research laboratory in which we live and operate. Interdisciplinarity is a crucial anti-rhetorical and anti-speciesism factor in this context. In its international artistic residencies and other DC's projects, the artist collaborates with scientists or experts on an environmental or landscape aspect. For instance, in the project entitled Le fogge delle rocce (2024), the artist works with a geologist on the subject of rock formations.

This partnership brought together complementary expertise and reorganized competencies, enabling a more integrated approach to research. By merging diverse perspectives, it fostered a deeper understanding of human landscapes and more holistic forms of inquiry. We formed a multidisciplinary team of scientists, artists, and a curator, where design practices met creative skills to explore new ways of interpreting place identity and its meaningful use. These discussions led to the development of experimental communication models now beginning to take shape. In particular, the artists engaged with the landscape as an active cultural and conceptual space rather than a passive backdrop. They did so by treating scientific geological data, cultural data, and geotrail design, which were defined through the process of co-creation, as a basis for a productive exchange of ideas.

The booklet-style guide presents the area's geodiversity and geoheritage in an engaging, accessible way, going beyond scientific explanation to inspire an emotional understanding of the landscape. Artistic elements translated complex geological information for non-specialists, while also adapting Walser narratives to highlight the depth of local vernacular knowledge. These enriched narratives combine technical, scientific, and cultural content across multiple media, creating a multifaceted, visually and artistically supported experience. The resulting small guide is an experimental prototype, open to further development in a precise, organic, and inclusive way. Culture and research do not produce a fixed product, but rather a flexible tool with many possible applications.

While collaboration has yielded numerous benefits, it has also brought to light a number of challenges. The integration of methodologies and priorities from distinct disciplinary traditions – science and art – necessitated a process of careful negotiation and a commitment to mutual understanding. Artists prioritized interpretation and emotional engagement, whereas scientists focused on precision and factual accuracy. Balancing these perspectives required time and effort, yet the resulting synthesis was both credible from a scientific perspective and convincing from an artistic perspective.

Despite the challenges, the integration of artistic collaboration significantly enhanced the efficacy of the geotrail in conveying geological knowledge in an inclusive and innovative way. The involvement of DC demonstrated how contemporary art can serve as an efficacious means of public engagement, transforming complex scientific data into experiences that inspire curiosity and appreciation for natural and cultural heritage. This experience underscores the potential of interdisciplinary partnerships as a model for future initiatives to bridge the gap between science, art, and society.

The study culminated in the creation of a booklet that serves as the geotrail guide. To address the diverse considerations inherent in geoscience communication, we incorporated elements emerged from the co-creation process into a multidisciplinary approach, working with artists to blend geological insights with narrative and visual art. These collaborations facilitated an interdisciplinary discourse on topics including scientific knowledge and information, and geotrails. In collaboration, we examined geoscientific communication as a vehicle for the dissemination of knowledge and content that pertain specifically to the mountains and their geomorphological features, ecosystems, and local contemporary society. We sought to establish a reciprocity of exchange between art and geology. The outcome was an artist's book that also served as a guide to this specific geotrail. In this project, the curator, geoscientists and artists collaborated to conceptualize the narrated and illustrated presentation of the geotrail and its geodiversity aspects. The final guide-book contains a comprehensive introduction, featuring an old Walser poem about the walking paths, a summary of the objectives of the geotrail, and a geotouristic map; and an in-depth explanation for each stage, that includes a detailed map, general description, an adapted Walser story by the artists, geological insights for the observation points, an interpretive box on geological or cultural aspects, brief commentary on nearby geosites, and custom illustrations created by the artists. The different stages are marked by the observation points. This approach fosters a layered exploration of the landscape, offering visitors a dual narrative journey. One journey delves into the cultural heritage and legends of the Walser, adapted with a modern perspective to highlight contemporary environmental issues and encourage cultural appreciation. The other is a geological journey back in time, guiding visitors through various observation points to explore changes from the last ice age to over 300 million years ago, unveiling the area's geological evolution. Through these integrated journeys, the guidebook supports a nuanced understanding of the landscape, encouraging visitors to interpret it through both geological and cultural lenses.

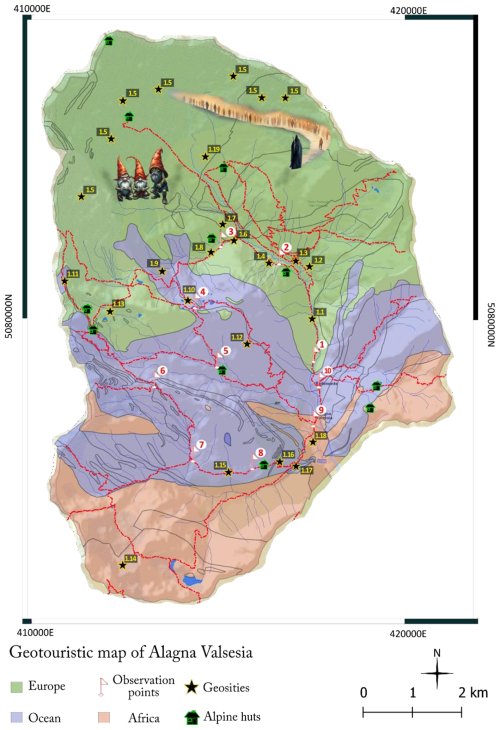

4.1 The Geotouristic map

A geotouristic map plays a crucial role in conveying scientific concepts to non-specialist audiences (Regolini-Bissig, 2010). In this study, the geotouristic map is a central communication element, fostering engagement with the geological heritage of the geotrail. By offering an accessible and visually compelling entry point, it attracts a broader audience and guides them through the narrative layers of the geotrail. To maximize its impact, it was critical to balance scientific accuracy with aesthetic appeal. Through collaboration with curator and artists, we opted to integrate both tourist and geoscientific components into the design (Fig. 8), resulting in an interpretive map (Regolini-Bissig, 2010). This map typology enables users, both scientists and non-specialists, to gain insight into geomorphological and geological phenomena, including landscape formation and evolution processes. Particularly in mountainous areas, such maps serve as effective geotourism tools, enhancing interpretation of complex landscapes and supporting a deeper appreciation of geological features (Bouzekraoui et al., 2018).

Figure 8Geotouristic map of Alagna Valsesia. it merges artistic and scientific elements, resulting in an artistic interpretation map. Map by the authors.

The geotourism map highlights selected geosites and provides introductory interpretations of the geological environment to engage visitors and introduce the geotrail narrative. It distinguishes three paleoenvironments (pre-Alpine European continental formations, the Tethys Ocean floor, and the African plate) displaying geological units by their formative contexts. Designed for scientific accuracy, the map guides visitors through observation points chosen with the Walser community, fostering deeper understanding along the trail.

Practical elements such as hiking routes and alpine huts enhance usability, while artistic illustrations rooted in Walser folklore highlight sites tied to traditional legends. These visuals preserve oral traditions, integrate contemporary art, and draw visitor attention, guiding them through layered geological and cultural narratives along the trail.

4.2 The Journey back in the Time

The primary layer of the geotrail narrative is related to the geology of the area. It invites visitors and readers of the guide to travel back in time by interpreting, step by step, visible rock formations and landforms from ten strategically selected observation points. These points, identified in collaboration with the local community through the co-creation process, represent the main points of the Alagna Valsesia territory, also giving significant insights of geology. At this layer, the emphasis is on geoscientific input, with minimal artistic contribution. During the co-creation process, all the participants expressed their surprise at understanding how old the rocks of Alagna Valsesia are, and how far back they come from, and it became clear how attractive the theme of a geological journey through time could be that would lead along the geotrail. Following this narrative thread, geoscientists interpreted the landscape for each observation point. Since Alagna Valsesia is situated in an alpine region, the geological narrative begins with the interpretation of recent glacial formations (Fig. 9), then proceeds deeper in time, detailing the processes of alpine orogenesis and rock formation.

Figure 9Interpreted glacial landscape in the upper part of Alagna Valsesia. This area is visible from the first observation point of the geotrail. Photo and illustration by the authors

This region is particularly well-suited to such an exploration due to its exceptional geodiversity (Guerini et al., 2024b), showcasing geological units from the European plate, the Adriatic plate, and the Tethys seafloor. The structure of this narrative sequence is illustrated in the Table 1.

Storytelling is an important method of communicating geoscience to non-specialist audiences, allowing complex knowledge to be communicated to both adults and children, engaging audiences and making them more informed, better able to understand and interpret their environment, and more likely to fully appreciate it (Lidal et al., 2013; Matias et al., 2020). However, our study revealed the necessity to enrich the local culture, which is strongly connected to the landscape. To this end, we collaborated with curator and artists who facilitated the integration of a multidisciplinary approach, thereby incorporating a second narrative layer based on locally rooted storytelling.

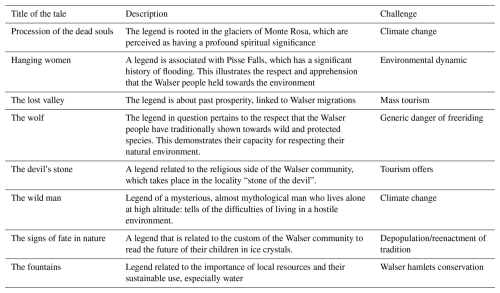

4.3 The tales

The second narrative level focuses on the vernacular knowledge of the Walser people. Vernacular knowledge covers a wide range of fields, including earth sciences, social sciences, architecture, and health. It combines these various domains into a coherent and holistic framework, which is frequently transmitted orally or through everyday actions (Smythe and Peele, 2021). Furthermore, this information is expressed in a variety of ways, including language, artistic expression, music, place names, dance, architecture, medications, environmental practices, storytelling, and so on. In our research, we concentrated on vernacular knowledge conveyed through practices and legends, which also preserve the typical Walser language. The co-creation process yielded a substantial corpus of these legends, which exemplified the oral tradition of the Walser. Once more, in collaboration with the local community, we selected the legends that are most deeply rooted and represent the community, their spiritual values, and their relationship to the environment. In particular, we jointly selected six legends and some specific aspects of the Walser traditions to be emphasized in the eight observation points (in the introductory and concluding points they were not considered). In the final stage of the co-creation process, we inquired of community members as to the principal challenges they perceived to be facing in their area and how these might be incorporated into the narratives. Thus, in collaboration with Walser members, we undertook a creative process whereby scientific and local community knowledge were integrated, and non-scientists were facilitated in being engaged in meaningful dialogue (Illingworth, 2020).

Subsequently, we initiated the artistic component. Based on the data gathered during the co-creation process, curators, artists and geoscientists collaborated by developing narratives and images that encapsulated both the local community and the contemporary issues prevalent in the area. These representations were created from their respective observation points (Table 2).

Table 2Titles and descriptions of the tales told at each observation point. Each tale is derived from Walser legends and traditions and has been repurposed by an artist to address a local contemporary challenge.

The result is a distinct form of storytelling, the locally rooted one, that draws upon the rich traditions of local communities while infusing it with a contemporary sensibility. The potential of locally rooted storytelling is to enhance conservation efforts by aligning actions with local worldviews and fostering meaningful connections between people and their landscapes (Fernández-Llamazares and Cabeza, 2018). In our case, the promotion of locally rooted storytelling can facilitate the transfer of Walser knowledge and language across generations, encourage local engagement, and enhance the resonance of geoconservation efforts.

This paper presents an innovative method of geoscience communication within the Sesia Val Grande Geopark. Projects with participatory approaches (Bollati et al., 2023) or trails for geological education (Perotti et al., 2020) have already been implemented in the geopark. In addition, geotrekking has recently been included in IGCP projects and, combined with multimedia tools, is considered an important tool for geoscience promotion and conservation in UNESCO Global Geoparks (Bollati et al., 2024). However, our work contributes to the advancement of the research landscape by proposing an innovative model for the development of communication strategies in the field of geoscience. This model integrates two key elements: co-creation and creative elements, both of which are essential for effective geoscience communication. Based on the successful integration of art with geoscientific communication (Nesci and Valentini, 2020) and the demonstration that two-way communication is optimal (Stewart and Lewis, 2017; Loroño-Leturiondo et al., 2019), this study integrated these two aspects by proposing a multidisciplinary approach for communicating the geological heritage of Alagna Valsesia through a geotrail. In a period during which an increasing number of geological trails are being established, these initiatives frequently fail to achieve their objective of disseminating geoscience due to their inability to attract and engage the public. In contrast, our approach enables the local community to perceive the project as their own matter, thereby enhancing its likelihood of success. Furthermore, through artistic collaboration, it permits the communication of geoscientific concepts by stimulating diverse audience segments, including the emotional one, which has been demonstrated to be a considerably more effective mode of communication than traditional methods (Ham, 2013).

This approach aligns well with UNESCO geoparks, which operate on a bottom-up model aimed at holistic territorial enhancement. Engaging long-established, historically rooted communities (like the Walser) in reciprocal communication supports objectives of UNESCO Global Geoparks by integrating vernacular knowledge, which, in turn, enhances geoscientific communication and responsiveness to local needs. This collaborative framework fosters community cohesion promotes sustainable land management, and, through artist involvement, cultivates a more comprehensive understanding of the region. Furthermore, the result of this project was an artist's book that also serves as a guide to geotrail, presenting a novel approach to science communication. This format not only provides a structured, guided experience for those walking the trail but also extends engagement opportunities beyond the physical site through the book and accompanying digital resources. Indeed, the guidebook was designed to be field-usable but is also suitable for distribution in schools or for sale as an art object that visually conveys Walser cultural heritage alongside the geological message.

To reach as wide an audience as possible, a digital version of the booklet (see Supplement) will be published soon on the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark website, in the themed trails section (http://www.sesiavalgrandegeopark.it/index.php/it/geoturismo/sentieri-tematici, last access: 20 November 2025). A few physical copies could also be printed and distributed free of charge by the Alagna Valsesia tourist office. While the bilingual version will be published on the website, only Italian-language copies could be provided to the tourist office, as most of the visitors to the area are Italian native speakers. This strategy eliminates the need for costly installations and maintenance of educational panels, which are particularly challenging in the complex and evolving environment of the Alps.

To facilitate the continuation of the co-creation process with the local community, it is essential that the inaugural presentation of the booklet be held in Alagna. This event should engage not only selected members of the Walser community but also the broader community at large. Indeed, the most significant limitation of this study is that it has not engaged the entire community. Additionally, as it is still in the planning phase, it has yet to make significant efforts to promote the geotrail. Furthermore, future work should monitor the dissemination of the guidebook and the success of the geotrail. To evaluate the effectiveness of the geotrail booklet in Alagna Valsesia, a combination of questionnaires, knowledge assessments, and qualitative feedback could be proposed. Questionnaires administered at the tourism office could assess the interest of the visitors, booklet usage, clarity, and overall satisfaction. Pre- and post-trail knowledge assessments, conducted by authorized Geopark guides during guided visits, would quantify gains in understanding geological formations, paleoenvironments, Walser cultural heritage, and people awareness on the treated themes. Complementing these, ongoing qualitative feedback collected by University of Turin researchers through interviews or focus groups with visitors and locals would provide insights on the effectiveness of the geotrail, assessing which aspects of the booklet were most engaging or informative, the perceptions of the integration of geological and cultural narratives, and collecting suggestions for improvements or additions. Together, these methods would offer a robust evaluation framework to guide future improvements, scaling strategies, and the integration of local knowledge into geotourism initiatives.

The data are partially available within the article and its Supplement. The other data are available from the corresponding author, MG, upon reasonable request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-9-87-2026-supplement.

MG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Supervision, Writing original draft, Writing editing and review; AF: Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing editing and review; GdIL: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing original draft.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

This article was produced by the authors on a voluntary basis and received no funding from external sources or grants. Since this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects, and no personal or sensitive data were collected, it did not require an ethical review. Considerations of good ethical practice included the involvement of only participants aged 18 or over and ensuring the anonymity of data. Other areas of good ethical practice included the dissemination of results and outputs back to involved communities and participants where possible. Moreover, verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We are thankful to all the representative of the Walser community who participated in co-create the communication strategy. We are grateful to Marco Giardino, Fabien Hoblea and Ludovic Ravanel, who co-directed the PhD thesis of the first author giving important scientific advice for this work. At the same time, the authors thank Emiliano Oddone, founder of the Dolomiti Project, for his important scientific advice on the promotion of geodiversity and his help during the Dolomitcontemporanee cooperation. Finally, we are tankful to Teresa de Toni and Stefano Collarin for their important support during the work at Dolomiticontemporanee. AI-based tools were employed to refine the English language in some parts of the manuscript.

This research has been supported by the Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (This project is a part of Michele Guerini's PhD project. The thesis was funded by Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca (MUR) through the PON program).

This paper was edited by Jenna Sutherland and reviewed by M. Tropeano and one anonymous referee.

AbdelMaksoud, K. M., Emam, M., Al Metwaly, W., Sayed, F., and Berry, J.: Can innovative tourism benefit the local community: The analysis about establishing a geopark in Abu Roash area, Cairo, Egypt, Int. J. Geoheritage Park., 9, 509–525, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJGEOP.2021.11.009, 2021.

Bollati, I. M., Caironi, V., Gallo, A., Muccignato, E., Pelfini, M., and Bagnati, T.: How to integrate cultural and geological heritage? The case of the Comuniterrae project (Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark, northern Italy), AUC Geogr., 58, 129–145, https://doi.org/10.14712/23361980.2023.10, 2023.

Bollati, I. M., Masseroli, A., Al Kindi, M., Cezar, L., Chrobak-Žuffová, A., Dongre, A., Fassoulas, C., Fazio, E., Garcia-Rodríguez, M., Knight, J., Matthews, J. J., de Araújo Pereira, R. G. F., Viani, C., Williams, M., Amato, G. M., Apuani, T., de Castro, E., Fernández-Escalante, E., Fernandes, M., Forzese, M., Gianotti, F., Goyanes, G., Loureiro, F., Kandekar, A., Koleandrianou, M., Maniscalco, R., Nikolakakis, E., Palomba, M., Pelfini, M., Tronti, G., Zanoletti, E., Zerboni, A., and Zucali, M.: The IGCP 714 Project “3GEO – Geoclimbing & Geotrekking in Geoparks” – Selection of Geodiversity Sites Equipped for Climbing for Combining Outdoor and Multimedia Activities, Geoheritage, 16, 1–27, https://doi.org/10.1007/S12371-024-00976-4, 2024.

Bouzekraoui, H., Barakat, A., El Youssi, M., Touhami, F., Mouaddine, A., Hafid, A., and Zwoliński, Z.: Mapping geosites as gateways to the geotourism management in central High-Atlas (Morocco), Quaest. Geogr., 37, 87–102, https://doi.org/10.2478/QUAGEO-2018-0007, 2018.

Chan, K. M. A., Balvanera, P., Benessaiah, K., Chapman, M., Díaz, S., Gómez-Baggethun, E., Gould, R., Hannahs, N., Jax, K., Klain, S., Luck, G. W., Martín-López, B., Muraca, B., Norton, B., Ott, K., Pascual, U., Satterfield, T., Tadaki, M., Taggart, J., and Turner, N.: Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 1462–1465, https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.1525002113, 2016.

Chauhan, R. S.: Unstructured interviews: are they really all that bad?, Hum. Resour. Dev. Int., 25, 474–487, https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2019.1603019, 2022.

Christillin, J.-J., Favre, E., Ronco, B., and Thedy, G.: Nell'alta Valle del Lys si racconta… = Kuntjini van Éischeme = Stòrene vòn Ònderteil òn Òberteil, edited by: Issime, C. di, Tipografia DUC, Issime, 143 pp., ISBN 978-88-87677-50-8, 2010.

Coratza, P., Vandelli, V., and Ghinoi, A.: Increasing Geoheritage Awareness through Non-Formal Learning, Sustainability, 15, 868, https://doi.org/10.3390/SU15010868, 2023.

da Silva, R. G. P., Henke-Oliveira, C., Ferreira, E. S., Fetter, R., Barbosa, R. G., and Saito, C. H.: Systematic Conservation Planning approach based on viewshed analysis for the definition of strategic points on a visitor trail, Int. J. Geoheritage Park., 8, 153–165, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJGEOP.2020.07.001, 2020.

D'Incà Levis, G.: Dolomiti Contemporanee, laboratorio d'arti visive in ambiente. Cura e rigenerazione di paesaggio e patrimonio, in: ALPI e ARCHITETTURA. Patrimonio, progetto, sviluppo locale, vol. 1, edited by: Del Curto, D., Dini, R., and Menini, G., Mimesis Edizioni, Milano, 293–304, ISBN 978-88-57536-54-5, 2016.

dolomiti contemporanee: Home page, https://www.dolomiticontemporanee.net/DCi2013/?page_id=3786, last access: 16 December 2024)

Farsani, N. T., Coelho, C., and Costa, C.: Geotourism and geoparks as novel strategies for socio-economic development in rural areas, Int. J. Tour. Res., 13, 68–81, https://doi.org/10.1002/JTR.800, 2011.

Fernández-Llamazares, Á. and Cabeza, M.: Rediscovering the Potential of Indigenous Storytelling for Conservation Practice, Conserv. Lett., 11, e12398, https://doi.org/10.1111/CONL.12398, 2018.

Flint, A.: Poetry, paths, and peatlands: integrating poetic inquiry within landscape heritage research, Landsc. Res., 49, 4–18, https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2023.2237432, 2024.

Gordon, J. E.: Geoheritage, Geotourism and the Cultural Landscape: Enhancing the Visitor Experience and Promoting Geoconservation, Geosciences, 8, 136, https://doi.org/10.3390/GEOSCIENCES8040136, 2018.

Guerini, M.: The path of Alpine sustainability. Participatory tools for taking care of the cultural and environmental heritage of the Monte Rosa massif (NW-Alps, Italy), Università degli Studi di Torino, Université Savoie Mont Blanc, Torino-Chambéry, https://theses.hal.science/tel-05351854v1, 2025.

Guerini, M., Khoso, R. B., Negri, A., Mantovani, A., and Storta, E.: Integrating Cultural Sites into the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (North-West Italy): Methodologies for Monitoring and Enhancing Cultural Heritage, Heritage, 6, 6132–6152, https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6090322, 2023.

Guerini, M., Hoblea, F., Giardino, M., and Ravanel, L.: Enhancing community engagement in geotourism: French Alpine interpreted landscapes as a model for an innovative participatory geotrail in the Sesia Val Grande Geopark (Italy), EGU General Assembly 2024, Vienna, Austria, 14–19 Apr 2024, EGU24-1648, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu24-1648, 2024a.

Guerini, M., Mantovani, A., Khoso, R. B., and Giardino, M.: Exploring the Correlation between Geoheritage and Geodiversity through Comprehensive Mapping: A Study within the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (NW Italy), Geomorphology, 461, 109298, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GEOMORPH.2024.109298, 2024b.

Gunnell, J. L., Golumbic, Y. N., Hayes, T., and Cooper, M.: Co-created citizen science: challenging cultures and practice in scientific research, J. Sci. Commun., 20, Y01, https://doi.org/10.22323/2.20050401, 2021.

Ham, S. H.: Interpretation-Making a difference on purpose, Fulcrum Publishing, Golden, Colorado, 320 pp., ISBN 9781555917425, 2013.

Harris, L. A., Garza, C., Hatch, M., Parrish, J., Posselt, J., Rosario, J. P. A., Davidson, E., Eckert, G., Grimes, K. W., Garcia, J. E., Haacker, R., Horner-Devine, M. C., Johnson, A., Lemus, J., Prakash, A., Thompson, L., Vitousek, P., Bras, M. P. M., and Reyes, K.: Equitable Exchange: A Framework for Diversity and Inclusion in the Geosciences, AGU Adv., 2, e2020AV000359, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020AV000359, 2021.

Higuchi, Y. and Yamanaka, Y.: Knowledge sharing between academic researchers and tourism practitioners: a Japanese study of the practical value of embeddedness, trust and co-creation, J. Sustain. Tour., 25, 1456–1473, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1288733, 2017.

Hose, T. A. (Ed.): Geoheritage and Geotourism, NED-New., Boydell & Brewer Ltd, Newcastle, https://doi.org/10.2307/J.CTVC16KJ7, 2016.

Hose, T. A.: Geotrails, in: The Geotourism Industry in the 21st Century, CRC Press, 247–275, https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429292798-13, 2020.

Hu, M., Świerzawski, J., Kleszcz, J., and Kmiecik, P.: What are the concerns with New European Bauhaus initiative? Vernacular knowledge as the primary driver toward a sustainable future, Next Sustain., 1, 100004, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NXSUST.2023.100004, 2023.

Illingworth, S.: Creative communication – using poetry and games to generate dialogue between scientists and nonscientists, FEBS Lett., 594, 2333–2338, https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.13891, 2020.

Illingworth, S.: A spectrum of geoscience communication: from dissemination to participation, Geosci. Commun., 6, 131–139, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-6-131-2023, 2023.

Illingworth, S. and Jack, K.: Rhyme and reason-using poetry to talk to underserved audiences about environmental change, Clim. Risk Manag., 19, 120–129, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CRM.2018.01.001, 2018.

Illingworth, S., Stewart, I., Tennant, J., and von Elverfeldt, K.: Editorial: Geoscience Communication – Building bridges, not walls, Geosci. Commun., 1, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-1-1-2018, 2018.

Le fogge delle rocce: dolomiti contemporanee – le fogge delle rocce, https://www.dolomiticontemporanee.net/DCi2013/?p=33625 (last access: 18 December 2024).

Lidal, E. M., Natali, M., Patel, D., Hauser, H., and Viola, I.: Geological storytelling, Comput. Graph., 37, 445–459, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CAG.2013.01.010, 2013.

Locritani, M., Merlino, S., Garvani, S., and Di Laura, F.: Fun educational and artistic teaching tools for science outreach, Geosci. Commun., 3, 179–190, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-3-179-2020, 2020.

Loroño-Leturiondo, M., O'Hare, P., Cook, S. J., Hoon, S. R., and Illingworth, S.: Building bridges between experts and the public: a comparison of two-way communication formats for flooding and air pollution risk, Geosci. Commun., 2, 39–53, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-2-39-2019, 2019.

Macadam, J.: Geoheritage: Getting the Message Across. What Message and to Whom?, in: Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management, edited by: Reynard, E. and Brilha, J., Elsevier, 267–288, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809531-7.00015-0, 2018.

Martin, S., Regolini-Bissig, G., Perret, A., and Kozlik, L.: Élaboration et évaluation de produits géotouristiques: propositions méthodologiques, Téoros Rev. Rech. en Tour., 29, 55–66, https://doi.org/10.7202/1024871AR, 2010.

Matias, A., Carrasco, A. R., Ramos, A. A., and Borges, R.: Engaging children in geosciences through storytelling and creative dance, Geosci. Commun., 3, 167–177, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-3-167-2020, 2020.

Nesci, O. and Valentini, L.: Science, poetry, and music for landscapes of the Marche region, Italy: communicating the conservation of natural heritage, Geosci. Commun., 3, 393–406, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-3-393-2020, 2020.

Newsome, D. and Dowling, R.: Setting an agenda for geotourism, in: Geotourism. The Tourism of Geology and Landscape, edited by: Newsome, D. and Dowling, R., Goodfellow Publishers Limited, Oxford, 1–12, ISBN 978-1-906884-09-3, 2010.

Nisbet, M. C., Hixon, M. A., Moore, K. D., and Nelson, M.: Four cultures: new synergies for engaging society on climate change, Front. Ecol. Environ., 8, 329–331, https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295-8.6.329, 2010.

Perotti, L., Bollati, I. M., Viani, C., Zanoletti, E., Caironi, V., Pelfini, M., and Giardino, M.: Fieldtrips and virtual tours as geotourism resources: Examples from the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (NW Italy), Resources, 9, 1–34, https://doi.org/10.3390/RESOURCES9060063, 2020.

Piana, F., Fioraso, G., Irace, A., Mosca, P., D'Atri, A., Barale, L., Falletti, P., Monegato, G., Morelli, M., Tallone, S., and Vigna, G. B.: Geology of Piemonte region (NW Italy, Alps–Apennines interference zone), J. Maps, 13, 395–405, https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2017.1316218, 2017.

Rangecroft, S., Clason, C., Dextre, R. M., Richter, I., Kelly, C., Turin, C., Grados-Bueno, C. V., Fuentealba, B., Camacho Hernandez, M., Morera Julca, S., Martin, J., and Guy, J. A.: GC Insights: Lessons from participatory water quality research in the upper Santa River basin, Peru, Geosci. Commun., 7, 145–150, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-7-145-2024, 2024.

Regolini-Bissig, G.: Mapping geoheritage for interpretive purpose: definition and interdisciplinary approach, in: Mapping Geoheritage, vol. Géovisions n° 35, edited by: Regolini-Bissig, G. and Reynard, E., UNIL, Lausanne, 1–13, ISBN 978-2-940368-10-5, 2010.

Rizzi, E. and Gianoglio, M.: I Walser e le Alpi, Ultimi Studi, Grossi, Domodossola, ISBN 978-8889751770, 2023.

Rock, J., McGuire, M., and Rogers, A.: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Co-creation, Sci. Commun., 40, 541–552, https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547018781496, 2018.

Rodrigues, J., Costa e Silva, E., and Pereira, D. I.: How Can Geoscience Communication Foster Public Engagement with Geoconservation?, Geoheritage, 15, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1007/S12371-023-00800-5, 2023.

Savi-Lopez, M.: Leggende delle Alpi, La memoria, edited by: Loeascher, E., Piemonte in Bancarella, Torino, 358 pp., ISBN 978-8888552538, 1993.

Senabre Hidalgo, H., Perellò, J., Becker, F., Bonhoure, I., Legris, M., and Cigarini, A.: Participation and co-creation in citizen science, in: The Science of Citizen Science, edited by: Vohland, K., Land-Zandstra, A., Ceccaroni, L., Lemmens, R., Perello, J., Ponti, M., Samson, R., and Wagenknecht, K., Springer, 1–529, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58278-4_11, 2021.

Shajahan, R., van Wyk de Vries, B., Zanella, E., and Harris, A.: Creating a sense of intangible science: Making it understandable to a broad public via geoheritage, Int. J. Geoheritage Park., 12, 396–415, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJGEOP.2024.07.007, 2024.

Sibilla, P.: Una comunità Walser delle Alpi: strutture tradizionali e processi culturali, XLVI., Biblioteca di “Lares”, Leo S. Olschki, Firenze, 283 pp., ISBN 9788822229526, 1980.

Smythe, W. F. and Peele, S.: The (un)discovering of ecology by Alaska Native ecologists, Ecol. Appl., 31, e02354, https://doi.org/10.1002/EAP.2354, 2021.

Stewart, I. S. and Lewis, D.: Communicating contested geoscience to the public: Moving from “matters of fact” to “matters of concern”, Earth-Science Rev., 174, 122–133, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EARSCIREV.2017.09.003, 2017.

Tormey, D.: New approaches to communication and education through geoheritage, Int. J. Geoheritage Park., 7, 192–198, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJGEOP.2020.01.001, 2019.

Trench, B., Bucchi, M., Amin, L., Cakmakci, G., Falade, B. A., Olesk, A., and Polino, C.: Global spread of science communication: Institutions and practices across continents, in: Routledge Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology, edited by: Trench, B. and Bucchi, M., Taylor and Francis, Routledge, London, 214–230, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203483794.ch16, 2014.

Valentini, L., Guerra, V., and Lazzari, M.: Enhancement of Geoheritage and Development of Geotourism: Comparison and Inferences from Different Experiences of Communication through Art, Geosciences, 12, 264, https://doi.org/10.3390/GEOSCIENCES12070264, 2022.

van Beveren, C. C., Fial, A., Slokker, T., Pilo, F., Alkema, S., and Wolfensberger, M.: Creating a sense of belonging through co-creation during COVID-19, J. Eur. Honor. Counc., 6, https://doi.org/10.31378/JEHC.171, 2022.

Van Loon, A. F., Lester-Moseley, I., Rohse, M., Jones, P., and Day, R.: Creative practice as a tool to build resilience to natural hazards in the Global South, Geosci. Commun., 3, 453–474, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-3-453-2020, 2020.

Wanner, K.: Sui sentieri dei Walser. escursioni, storia, folklore, 3rd Edn., Grossi, Domodossola, 257 pp., ISBN 9788885407398, 1995.

Weigold, M. F.: Communicating Science: A Review of the Literature, Sci. Commun., 23, 164–193, https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547001023002005, 2001.

Wheeler, M.: Tourism marketing ethics: An introduction, Int. Mark. Rev., 12, 38–49, https://doi.org/10.1108/02651339510097720, 1995.

Wibeck, V., Eliasson, K., and Neset, T. S.: Co-creation research for transformative times: Facilitating foresight capacity in view of global sustainability challenges, Environ. Sci. Policy, 128, 290–298, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2021.11.023, 2022.

Widawski, K. and Oleśniewicz, P.: Thematic Tourist Trails: Sustainability Assessment Methodology. The Case of Land Flowing with Milk and Honey, Sustainability, 11, 3841, https://doi.org/10.3390/SU11143841, 2019.

Wijnen, F., Strick, M., Bos, M., and van Sebille, E.: Evaluating the impact of climate communication activities by scientists: what is known and necessary?, Geosci. Commun., 7, 91–100, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-7-91-2024, 2024.

Wings, O., Fischer, J., Knüppe, J., Ahlers, H., Körnig, S., and Perl, A.-M.: Paleontology-themed comics and graphic novels, their potential for scientific outreach, and the bilingual graphic novel EUROPASAURUS – Life on Jurassic Islands, Geosci. Commun., 6, 45–74, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-6-45-2023, 2023.

Zhang, Y. and Wildemuth, B. M.: Unstructured Interviews, in: Applications of social research methods to questions in informations and library science, edited by: Wildemuth, B. M., Libraries Unlimited, Santa Barbara, 239–247, ISBN 978-1-4408-3904-7, 2017.