the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

How to get your message across: designing an impactful knowledge transfer plan in a European project

Sara Pasqualetto

Thomas Jung

Academic research is largely characterized by scientific projects striving to advance understanding in their respective fields. Financial support is often subject to the fulfilllment of certain requirements, such as a fully developed knowledge transfer (KT) plan and dissemination strategy. However, the evaluation of these activities and their impact is rarely an easy path to clarity and comprehensiveness, considering the different expectations from project officers and funding agencies or dissemination activities and objectives. With this paper, based on the experience of the management and outreach team of the EU-H2020 APPLICATE project, we aim to shed light on the challenging journey towards impact assessment of KT activities by presenting a methodology for impact planning and monitoring in the context of a collaborative and international research project. Through quantitative and qualitative evaluations and indicators developed in 4 years of the project, this paper represents an attempt to build a common practice for project managers and coordinators and establish a baseline for the development of a shared strategy. Our experience found that an assessment strategy should be included in the planning of the project as a key framing step, that the individual project's goals and objectives should drive the definition and assessment of impact and that the researchers involved are crucial to implement a project's outreach strategy.

- Article

(1847 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Assessing the impact of publicly paid initiatives and projects is very important for gaining a better understanding of, among other things, the relevance of the initiative and its subject, the success in enhancing knowledge on a particular issue, and the effectiveness of the use of funding. Especially in the context of scientific research, measuring impact has become an increasingly relevant aspect for funding agencies in the conceptualization of proposals as well as in the reporting phase. When evaluating the impact of research initiatives, for example on policy-making and industrial practices, there are many aspects to consider, such as the purposes of the assessment, the contexts in which it is needed, as well as its scale (Morton, 2015).

Literature in this regard exists, with detailed and insightful examples coming especially from the non-peer-reviewed literature of research projects and funding institutions. For example, a 2015 document from the European Commission dealing with Horizon 2020 indicators defines impact as “the wider societal, economic or environmental cumulative changes over a longer period of time”, for which “impact indicators represent what the successful outcome should be in terms of impact on the economy/society beyond those directly affected by the intervention” (European Commission, 2015). When discussing methodologies to assess the impacts of higher-education institutions on sustainable development, Findler et al. (2019) state that “impacts refer to the effects that any organization, such as a [Higher Education Institution], has outside its organizational or academic boundaries on its stakeholders, the natural environment, the economy, and society in general”. Moreover, impact can concretize in different areas, from economy to policy making, and it can be directly or indirectly attributed to a project or institution (Findler et al., 2019). However, why is it important to keep track of a research project's impact and provide measurable assessments to evaluate it? For Upton et al. (2014), impact assessment serves a double function: it provides proof of the success of an initiative, project, or institution, and it works also to incentivize future endeavors towards enhancing this impact.

There are many examples that present different strategies and approaches to assessing the impact of research initiatives or institutions. However, a generalized assessment of how to tackle this key aspect when applied to the evaluation of the performance of knowledge transfer (KT) activities is still lacking. We refer here to the definition provided by the University of Cambridge (2009), which defines KT as “the transfer of tangible and intellectual property, expertise, learning and skills between academia and the non-academic community”. Some contributions dealing with measuring the impact of KT efforts have looked, for example, into the impact of single dissemination practices, such as the use of posters, on the success of KT (Rowe and Ilic, 2009) or have discussed the evaluation of KT activities and their impact on larger policies involving the agricultural sector and public funding (Hill et al., 2017), but there is no comprehensive attempt to present a fully developed methodology for the evaluation of KT actions in research. Especially in the panorama of research funding and science projects, guidelines on the matter are often unclear and are largely based on the application of a set of quantitative metrics known as key performance indicators (KPIs), which often provide insightful knowledge on the reach of each activity, e.g., the number of people who view a post or attend a talk but who are not always adequate to measure the uptake of this activity, meaning, for example, the number of people that make use of that knowledge (Morton, 2015). Moreover, different requirements to assess impact in KT initiatives might be subjective to the project advisers overseeing the performance of the individual projects and therefore might differ among advisers, even within the same funding agency. Finally, the impact assessment of KT aspects does not play a defining role in the conceptualization of communication and dissemination strategies, as they are usually relegated to being a collection of numerical indicators during the reporting phase.

With this paper, we aim to address this issue and present a road map for the development of a successful impact plan for research projects. We will outline our methodology as it was implemented in the APPLICATE project, present the outcomes and the strengths of this method, and discuss some lessons learned from the project.

To do so, in the following sections we will describe the APPLICATE project, its purpose, and its messages to outline the context in which this work came about. An overview of APPLICATE's knowledge transfer strategy will follow as applied in four different aspects: communication and dissemination, user and stakeholder engagement, training, and clustering. In the fourth section of the paper, we will present the project's methodology to monitor and report impact in a quantitative and qualitative manner and close with key lessons learned and recommendations and some conclusive remarks.

APPLICATE is a European project funded through the Horizon 2020 Research Programme, involving 15 research institutions, universities, and national weather centers from eight European countries and Russia. The project, which ran over 4.5 years and ended in April 2021, brought together expertise from scientific communities working with weather and climate models to assess the impact of Arctic changes at mid latitudes and to respond to specific stakeholder needs for enhanced predictive capacity in the Arctic region from weather to climate timescales. A wide range of stakeholders and users was therefore included in the project through the User Group and other project outreach activities. They were regularly consulted to effectively exchange knowledge on the latest science and user needs.

Throughout the project lifetime, the APPLICATE community has

-

developed and advanced cutting-edge numerical models and produced climate assessments which contribute to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Report 6 (AR6). APPLICATE has contributed to the assessment of weather and climate models (including models participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6, CMIP6) in the Arctic (Notz and SIMIP Community, 2020). This, along with the availability of new freely available software, will result in critical recommendations for future model development efforts, leading to better forecasts and projections (Blockley and Peterson, 2018).

-

It has delivered novel datasets contributing to the World Meteorological Organisation's Year of Polar Prediction (YOPP) (Bauer et al., 2020) to assess the impact of Arctic climate change on the rest of the Northern Hemisphere (Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project, PAMIP) (Smith et al., 2019) and provided a consolidated view of the underlying mechanisms and sources of uncertainty.

-

It has provided detailed recommendations for an optimized Arctic observing system taking into account different needs such as forecasting and monitoring (Ponsoni et al., 2020; Keen et al., 2021; Lawrence et al., 2019).

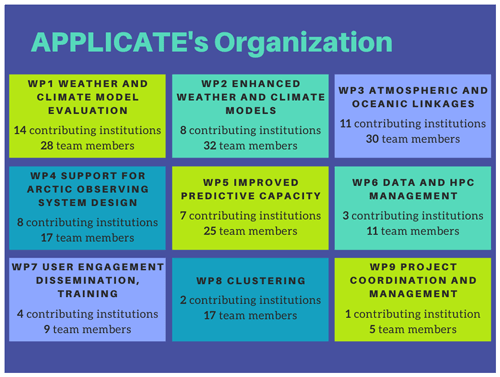

The project researched Arctic transformations and their impact on lower latitudes by approaching the issues from different sides: nine work packages were established to answer and find solutions to critical questions related to, among others, model evaluation and development, predictive capacity, and the Arctic observing system. The graphic below illustrates the topics and composition of the various work packages.

It is important to point out, however, that for Work Packages 7 and 8, although the coordinating aspects were curated by the members and institutions illustrated in the graphic, every person participating in any form in the project was asked to contribute to the KT and clustering efforts of APPLICATE.

In APPLICATE, knowledge transfer (KT) is intended as the process through which the knowledge and results produced within the project are shared with relevant groups and individuals within and outside the project to help them address the challenges of climate change while also fostering innovation and economic and societal growth. KT within APPLICATE focused on four main (groups of) activities: (1) outreach, communication, and dissemination, (2) stakeholder engagement, (3) training, and (4) clustering. These activities were carried out within Work Package 7 (WP7), although each work package was required to contribute to the efforts of disseminating results and engage in outreach and education efforts. The team of WP7 included both social and natural scientists, with expertise in communication and outreach strategies, co-production of climate services, and training in research.

The specific objectives of knowledge transfer were to

-

increase public awareness about the impact of Arctic changes on the weather and climate of the Northern Hemisphere (outreach),

-

develop relevant forms of communication within and outside the EU to adequately convey the results and recommendations to inform policy and socioeconomic actions (communication),

-

maximize exposure of the science produced to end-users, stakeholders, and the public at large and communicate project results in order to ensure knowledge sharing and knowledge exchange with stakeholders (dissemination),

-

contribute to servicing those socioeconomic sectors in the Northern Hemisphere that benefit from improved forecasting capacity (e.g., shipping and energy generation) at a range of timescales as well as enhancing their capacity to adapt to long-term climate change (stakeholder engagement),

-

improve the professional skills and competencies for those working and being trained to work within this subject area (training), and

-

ensure effective collaboration with partners from Europe and the wider international community (clustering).

In the following, we summarize the main points of the APPLICATE outreach, communication and dissemination plan, user engagement plan, training plan, and clustering plan. For each plan we describe

-

the goal of the KT activity,

-

the target audience, and

-

the team or person in charge of coordinating the KT activity.

3.1 Outreach, communication, and dissemination

As APPLICATE scientists strove to understand the linkages between changes in the Arctic climate and weather and climate at the mid latitudes, the communication team of the project sought to increase awareness of these linkages as well as the policy relevance of the research and aimed to maximize the impact of scientific findings for end-users and stakeholders. The terms “stakeholder” and “user” are used interchangeably and include all those that can be interested in and/or can benefit from better knowledge of the weather and climate in the Arctic and the Northern Hemisphere. Through targeted activities directed at different partners from the scientific community, industry, as well as local and indigenous communities, APPLICATE's communication and dissemination team sought to establish and maintain an effective dialog with a network of key stakeholders for a mutual exchange of information on the project and feedback on its activities. Targeted activities included dedicated meetings and workshops with users to update on the progress and results of the project, policy events to engage with policymakers within EU institutions, and press releases to appear in news outlets addressing the non-scientific public. Thus, communication efforts within the project were essential not only to produce an “outbound” of information (from the project scientists to the broader community), but also for an “inbound” to collect feedback and valuable impressions from the users of weather and climate services as well as stakeholders in the Arctic region and beyond.

In order to fulfill these objectives, the communication team identified key tools and platforms (some of which are shortly explained below) to strengthen the project results while keeping open the information flow from the public. Each of the activities was dedicated to convey specific messages and information to determined target groups.

The first, most prominent channel of communication was the project website1. It served as an “entry-level user interface” (Hewitt et al., 2017), central server for materials, information, and activities carried out in the framework of APPLICATE. In the information infrastructure of the project, the website represents the central hub: all the side activities pass through the website, which functions as a re-directory platform for more specific communication activities. The project website is designed to attract all audiences, each of which will then navigate it in different ways to find the information relevant for them.

Publications are the primary channel for scientific findings and thus key instruments for the broad dissemination of the project and its relevance, particularly among the scientific community. They are indicators of the scientific excellence of the project and provide the “manifesto” of the APPLICATE research for other scientists and projects.

Other fundamental tools for the dissemination of project results and research were conferences and meetings. These occasions represented opportunities that were essential for the presentation of the work carried out in APPLICATE to various audiences and groups, from fellow scientists to industry and policy makers. As Hewitt et al. (2017) describe in their paper, “such activities enabl[e] co-learning and co-development of products and services”. This is an aspect of the communication strategy that heavily relies on the involvement of scientists and researchers to present their studies and connect with the community.

The project has also established its presence on social media: the APPLICATE Twitter profile has been set up with the objective of communicating in a quick and relatable way the events, activities, and progress of the project to relate to a broader public that goes beyond the academic, political, or industrial frameworks and ultimately to maintain an easier contact with projects and institutes that carry out similar studies.

Other information materials have then been produced to convey specific information to targeted audiences, often in institutional frameworks. These documents include, e.g., policy briefs, which summarize valuable information presented in a way that would especially target policy makers and governmental officials, presented during policy events and workshops.

At the beginning of the project a list of target stakeholders addressed by the APPLICATE project and their communication requirements was developed which included the target audience of the communication, objective, and content of the communication, the type of language (e.g., technical, functional, industry-dependent, non-specialist), the primary mean of the communication along with the timing and the responsible team member to guide all the team members and especially the Executive Board, the coordination team, and the communication and dissemination teams (Johannsson et al., 2019).

3.2 Stakeholder engagement

The stakeholder and user engagement activities of the APPLICATE project were described in the Deliverable 7.3 User Engagement Plan (Bojovic et al., 2019). By pro-actively engaging users and involving them in feedback exchanges and in contributing to the development of climate products and services that respond to the actual needs of the community, the latest advances in forecasting system development can be effectively communicated to and benefit those economic sectors and social aspects that rely on improved forecasting capacity.

To develop and conduct targeted user engagement activities and foster co-production of knowledge in the project, we have divided users into three categories.

-

Key users – business and governmental stakeholders in the Arctic, within and outside the EU

-

Primary users – the scientific community, meteorological and climate national services, NGOs, and local and indigenous communities

-

Secondary users – business stakeholders from mid latitudes.

The APPLICATE community increased the stakeholder relevance of its research by applying a co-production approach (Bojovic et al., 2021) that continuously took into account user needs and feedback to the APPLICATE results via the User Group, workshops, meetings, interviews with key stakeholders, virtual consultations, and development of case studies and policy briefs, hence directly impact by improving stakeholders' capacity to adapt to climate change.

A group of stakeholder representatives and users of climate information (User Group) was set up at the beginning of the project, including Arctic stakeholders and rights holders (e.g., businesses, research organizations, and local and indigenous communities). The User Group acted as an advisory board external to the project that through the stakeholder engagement team could counsel the scientists on their information needs, existing gaps in data, and more widely the issues they encountered in adapting to climate change and where the project could provide results. User Group members also learned directly from the project the latest information available on Arctic climate change, thereby serving as “ambassadors” of the project team to their respective communities of practice by involving them in defining which environmental parameters (e.g., sea ice extent, number of frost days) would be useful for them to know in advance to plan business operations (e.g., shipping, reindeer herding).

Stakeholder engagement was primarily led by the stakeholder engagement team within WP7, who worked at the interface between users of climate data and the scientists within the project. This link worked in both directions: from the project to the users to inform on the scientific results and their applicability in various societal sectors and from the users to the scientists within the project to collect information on the needs and requirements, identify research gaps, and work together to co-produce relevant scientific outcomes.

Early in the project, a list of key stakeholders with whom to interact and to target with tailored communication and dissemination activities had been identified. From EU policy makers to providers of climate services and industry and civil society, the work package leaders have identified possible audience groups that have interests in the research carried out within APPLICATE. Not only the target groups would be end users of products and results developed by the scientists working on the project, but they would also provide feedback on the work done and help design a path for future research and developments.

An example of activity to engage with users of climate information is the blog “Polar Prediction Matters”2 initiated by APPLICATE together with the WMO initiative YOPP and the H2020 project Blue-Action, hosted on the Helmholtz Association website. This platform has been built with the aim of reaching out to end users of weather and climate services in the polar regions and facilitating a dialog between those who research, develop, and provide polar environmental forecasts and those who (could) use these results to guide their decisions. It has been a key tool to gain feedback on the products and services developed by the projects and forecast centers.

3.3 Training

The training activities of the APPLICATE project not only aimed to improve the professional skills and competencies of those working and being trained to work within the project, but it also provided a legacy for future generations of scientists and experts working in the fields of climate and weather prediction and modeling.

As part of WP7, the Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS) in cooperation with APPLICATE scientists and the coordination team developed and conducted comprehensive and targeted in-person and online training events and resources for early-career researchers, addressing a variety of topics and skills, some of which are specific to the subject of polar prediction and some others transferable (e.g., project management, science communication).

To optimize efforts, a training plan had been developed at the beginning of the project with a list of possible training activities along with their timing and modalities of delivery, which was updated throughout the project's lifetime (Fugmann et al., 2019).

Examples of training activities developed and delivered within the APPLICATE project include online seminars, training sessions at the project General Assemblies, a summer school, training workshops, and an online course. All activities were followed by feedback sessions or surveys, and the results were collected in deliverable 7.10 “Assessment of early career researchers training activities” (Schneider and Fugmann, 2020). Among the end results of the courses, participants strongly appreciated the syllabus and content of the training, in particular the combination of theoretical and practical aspects, while lessons learned were mostly of a logistical nature, such as improvements in the organization of the event.

3.4 Clustering

The clustering activities of the APPLICATE project were carried out within Work Package 8 to facilitate coordination and exploit synergies for a number of European and international activities that are related to some of the activities planned in APPLICATE. The strategy employed was to focus on a limited number of clustering activities that were given full attention with the aim of ensuring effective collaboration with partners from Europe, North America, and the wider international community.

A clustering plan has been developed at the beginning of the project to identify major European and international projects and players focused on advancing polar prediction capacity and understanding the impact of climate change in the Arctic (Jung et al., 2019). In the plan, updated throughout the project's lifetime, each target cooperating projects and initiatives is linked with a project team member who is responsible for the collaboration and for reporting to the executive board on clustering activities.

Clustering within APPLICATE has been done on both the scientific and coordination levels. At the scientific level, experiments and publications have been developed together with the international Arctic modeling community (e.g., with the EU Modelling Cluster of projects funded by the European Commission or with projects participating in the CMIP6-endorsed Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project and in the Sea Ice Model Intercomparison Project) and involved primarily the project scientists and task leaders. At the coordination level, clustering was established through organization of events, preparation of documents, and activities with other projects and programs focused on the polar regions but not necessarily on numerical modeling (e.g., the “EU Polar Cluster” of projects funded by the European Commission or activities in cooperation with the WMO's Polar Prediction Project) and involve primarily the coordination team, the stakeholder engagement team, and the communication team.

The main purposes of KT activities in APPLICATE include maximizing exposure, increasing awareness, and conveying key results to the wider community of researchers, policymakers, and businesses. Therefore, we consider “impact” to be any significant advancements in expanding the community awareness related to Arctic–mid-latitude linkages and Arctic weather and climate research, disseminating the results of APPLICATE's research and, in general, enlarging the horizons for knowledge exchange and research uptake. In this section, we list the aspects of the project's KT strategy that were instrumental towards this objective, and we present, for each of them, a set of quantitative and qualitative indicators to assess the impact of the action.

4.1 Outreach and dissemination

In the APPLICATE project, we made use of different tools to measure and assess the impact of our communication activities. Different instruments may be applied to different types of initiatives or actions, and here we illustrate how these have been applied in APPLICATE.

4.1.1 Dissemination and outreach activities

Meetings, conferences and workshops, press releases, webinars, and videos are all fundamental platforms for the dissemination of project results. The impact of these activities cannot only be measured in terms of how many events have been attended or organized by project scientists, but it is also worth considering the nature of the event (i.e., the type of event, size, targeted community, or type of arrangement): for example, an international conference has a higher impact index than a project meeting, considering both the number of people and the variety of audiences and disciplines they may attract. To gather the most information on the reach and uptake of these events, it is recommended to monitor and evaluate meetings and workshops not only after their conclusion, but also during the event itself and before (Hewitt et al., 2017).

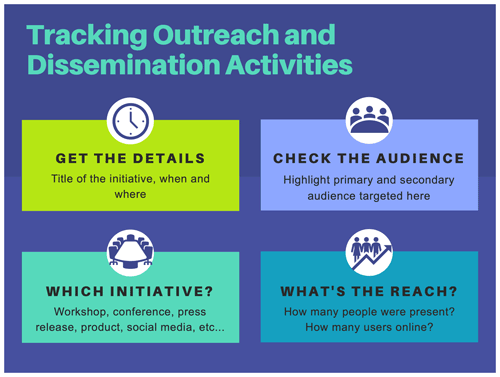

The project has therefore set up a database to collect information about the events or initiatives organized by participants of the project or for which project partners participated and presented the project results. The information requested and collected in the spreadsheet is based on criteria required by the European Commission in its project portal and is graphically summarized in Fig. 2. For each entry, the database shows key identification information, such as

-

the title of the meeting or initiative, together with the date and place of occurrence,

-

the type of action, which can entail participation in the organization of a conference, workshop, or event other than these non-scientific and non-peer-reviewed publications, or press releases, flyers, exhibitions, videos, films, and social media campaigns and other media presences, e.g., radio or TV interviews or participation in or organization of brokerage and pitch events,

-

the primary and secondary audiences attending the event,

-

an estimated number of the people reached during the initiative, and

-

the type of APPLICATE users targeted by the initiative.

Figure 2Schematic summary of the most relevant aspects to track and evaluate the performance of outreach and dissemination activities.

The main objective of this database is to have a comprehensive overview of the places and audiences reached by APPLICATE initiatives to be able to assess the scope of these efforts on the one hand and to evaluate the pertinence with the communication strategy and its objectives on the other. The latest point would include an evaluation of the target audience, i.e., if the events organized or attended reached out to the intended target group and if there are groups that these initiative fail to engage, thereby opening the path towards a correction of the strategy and the development of an ameliorated plan.

4.1.2 Zenodo and Google Scholar: the publication archives

In academic research, peer-reviewed publications are fundamental indicators of scientific impact. The number of publications released in the framework of the project as well as their reach (“How many citations did they generate? Which journals have we published in?”) make up a significant part of the puzzle when discussing communication impact.

The APPLICATE project collects all its relevant published and unpublished work in the online repository Zenodo. This online platform developed by CERN and OpenAIRE provides a community space where publications, conference proceedings such as abstracts, presentations, and posters as well as project documents like deliverables are streamed into a collective space. All participants in the APPLICATE project may upload directly their contributions to the platform.

The use of Zenodo makes it easier for everyone who has interest in the work of the project to see the concrete results of our research, but it is also an important tool for monitoring and retrieving important analytical information that relates to scientific publications within the project. It is easy, for example, to evaluate the stream of publications and their trend throughout the project duration or to retrieve information regarding paper impact and metrics.

Since January 2021 and in view of the final phase of the project, the management team has set up a project profile on Google Scholar, a platform commonly used by researchers to retrieve publication information about colleagues but not widely used for institutions or single initiatives. The advantage we found in using this method is primarily the automatization in measuring key figures such as citations, which helps greatly in having a quantitative overview of the reach and impact of the single publication as well as of the project in general. Indicators like the h index give a solid benchmark for evaluation and comparison with the rest of the community.

4.1.3 Twitter and website data

A significant part of the communication efforts of the APPLICATE team passes through the project website and its Twitter account. Both these spaces provide insightful analytics data that show the activity of the two platforms, its reception among the users and public, and the trend of this presence overtime. Indicators such as the engagement rate, the number of visits, and geographical access and reactions to posts and campaigns can give a rather accurate description of how the project's channels of communication are working and how well they are serving the overall communication strategy.

While Twitter makes its analytics available through the embedded service Twitter Analytics, each website can measure traffic and other data through various tools, which may come directly with the enabling platform like WordPress or via external providers. For APPLICATE, the chosen platforms to collect said data are Google Analytics and Matomo.

4.2 Stakeholder engagement

Stakeholder engagement activities are particularly important for assessing the impact an initiative or a project has on the broader community and for understanding the capacity of the project's team to interact across disciplines and topics. It is therefore key to finding efficient ways to measure quantitatively and qualitatively the impact that these activities have.

4.2.1 Case studies

The APPLICATE case studies are a series of self-explaining short documents (with a maximum of nine pages) covering a wide range of relevant topics in Arctic research and polar prediction, including the effects of Arctic environmental changes at mid latitudes. APPLICATE develops case studies to show the use of weather, climate, and sea ice information in the case of specific events with a significant impact on certain sectors or communities. The events analyzed in the case studies are selected together with users in User Group meetings, in thematic workshops, or through interviews.

The Stakeholder Engagement team in APPLICATE developed four case studies, a number that in itself can provide an indication of the level of involvement and influence the team in its users of reference. The impact of the case studies has been assessed also by checking the amount of downloads through the website and the other distribution channels (e.g., Zenodo), the number of contributors that helped develop the studies, the number of channels in which they have been featured, the events and meetings in which these documents have been presented, as well as how the information of the case studies have been used and applied in other contexts (see more about this under “Survey on knowledge transfer”).

4.2.2 Blog articles on Polar Prediction Matters

Polar Prediction Matters is a dialog platform developed by the Polar Prediction Project that serves to enable exchanges between providers of polar weather and sea ice prediction products and the users of forecasts in the polar regions. As an important player in the field of polar weather and climate prediction and in an effort to enhance the reach of its stakeholder interactions, the APPLICATE team and its stakeholders contributed three articles to the platform (Octenjak et al., 2020; Ross, 2020; Gößling, 2017), collaborating with users and presenting its own research dealing with applications of numerical predictions in the Arctic. The impact of these has been assessed through the evaluation of analytics from the website, online interactions on social media and other APPLICATE spaces, as well as evaluation of the number of collaborators involved in the articles.

4.2.3 Policy briefs

One of the objectives of European projects is to provide expertise and knowledge to inform policy-making bodies regarding compelling issues and to shape the future of research, directing science and policy towards new frontiers and relevant paths. While the relation between science and policy is not easy, many examples confirm the importance of scientific projects in shaping European and global policy (Lövbrand, 2011). In this perspective, the stakeholder engagement team has developed a series of policy briefs (Terrado et al., 2021), with the intention of summarizing some of the key findings of APPLICATE's scientific efforts and translating them into accessible and useful information that could direct and inform policy makers. To assess how impactful these documents will be, a look at the citations, especially in institutional documents and papers aimed at informing and shaping the future of research programs, is fundamental, as well as an analysis of access data from analytics provided by website traffic and downloads. It is important to state here that, due to the publication of these briefs being so close to that of this paper, a full and comprehensive analysis of the documents' impact is still to be made.

4.2.4 Survey User Group

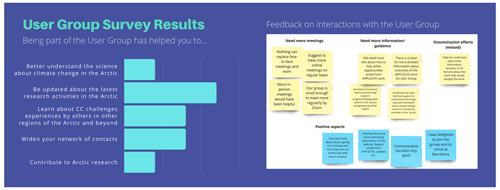

Members of the APPLICATE User Group (UG) participated in a survey that aimed to collect their feedback and assess their perception of how they have benefitted from being part of the APPLICATE UG and how the interaction with them has been conducted during the past 4 years (Fig. 3). UG members indicated that they benefitted from participating in the project in a variety of ways, including being regularly updated on the latest research in Arctic climate, learning about climate change issues and challenges faced by others in the Arctic, and also widening their professional networks.

4.3 Training

Educating the next generation of polar researchers has been one of the core aspects of the dissemination efforts within APPLICATE. The transfer of knowledge from mid-level and senior scientists to early-career researchers has great potential for transmitting and spreading not only scientific results, but also research approaches and methodologies that have been developed within the project beyond the framework of the initiative. When measuring the reach of a project, its efforts in organizing training events are important aspects to evaluate and assess.

The APPLICATE Education Team has organized three main activities:

-

the APPLICATE webinar series, a video collection outlining three of the main topics of the APPLICATE project;

-

the Polar Prediction School, in 2018 (in collaboration with the Polar Prediction Project and the Association of Polar Early Career Scientists – APECS) (Tummon et al., 2018);

-

the APPLICATE–YOPP–APECS online course, held in 2019 to provide an overview of the state-of-the-art knowledge of northern high-latitude weather and climate predictions.

By-products resulting from some of these initiatives are video recordings (called “FrostBytes”) illustrating research topics and questions on which early career researchers are focusing, which are also used to determine the influence of the project on the community at large. Ways to evaluate training activities include, among others, a quantitative assessment of the students attending these initiatives, which gives a good understanding of the breadth of the community that could be impacted and the monitoring of online performances of videos and materials produced during these activities. From a qualitative approach, the APPLICATE team has used feedback surveys to evaluate the quality of the initiatives along with the effects that teaching and training had on the research of the students or the likelihood of using the knowledge they gained in other applications. A summary of these evaluations and of the impact of the training events in APPLICATE has been reported in one of the project's deliverables (Schneider and Fugmann, 2020). The results of these surveys highlight, among other aspects, a general appreciation for the content tackled during the training and emphasized a need for more occasions to confront senior scientists in addition to evaluation of more organizational aspects.

4.4 Clustering

Evaluating the results of a project's clustering engagements can provide a useful insight into how the project was able to establish connections beyond its consortium boundaries and, therefore, can draw a picture of the spread of the scientific results and methodologies of the project.

APPLICATE researchers have been involved in collaborations and cooperation with different actors and initiatives on multiple levels. The partners actively participating in the project have developed national links with key stakeholders or institutes contributing to APPLICATE's research interests. The Clustering Team was particularly involved in engaging and strengthening collaborations with other H2020 projects in Europe, participating in events and initiating clustering opportunities like the EU Polar Cluster and the EU Modelling Cluster. Several scientific collaborations were supported by APPLICATE research, in particular the Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP) (Smith et al., 2019) and the Sea Ice Model Intercomparison Project (SIMIP) (Notz et al., 2016). Strong ties have also been established with partners in North America and with the endorsing Polar Prediction Project, the framework of YOPP (Jung et al., 2016).

All these initiatives have the potential to create not only a stronger modeling and polar community, but also a set of concrete outcomes that can be presented as producing project impact. Among others, we measured the number of publications resulting from the interaction with external partners (i.e., institutes and universities that were not receiving funds directly from an APPLICATE grant agreement) and the number of events and workshops organized with fellow projects thanks to the communication and dissemination spreadsheet outlined in previous paragraphs, with an estimation of the number of people reached by the event.

4.5 Survey on knowledge transfer

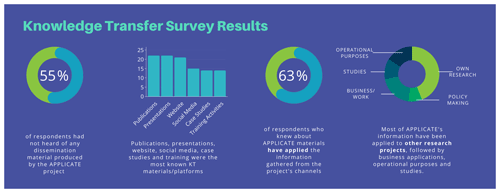

In order to implement a holistic evaluation of APPLICATE's efforts in KT, in particular to acquire insights into qualitative aspects of the activities that could not be represented by analytics and quantitative figures, in May 2021 the team distributed an evaluation survey to APPLICATE's User Group. These included some established relationships (i.e., the User Group that supported APPLICATE in its stakeholder interactions) as well as external projects and communities with which the project only partially interacted. The survey, shared through APPLICATE's online channels, was meant to assess the knowledge of the community regarding materials and information disseminated through APPLICATE and understand the breadth of applications of the knowledge generated through the project in other initiatives, studies, and policies. The questionnaire was created using Google Forms and was adapted to fit the knowledge of the respondents. Alternating yes–no questions with multiple-choice and open questions, the respondents could give feedback based on their knowledge of the projects' dissemination efforts. The first question aimed to discern the respondents who were already familiar with APPLICATE and its information from those who did not know about the project's dissemination channels. The second question asked specifically which of the KT materials (research publications, case studies, or social media accounts) the respondents knew and whether they had the chance to apply the information gathered from APPLICATE's KT activities in any other way. The third part of the survey assessed the main applications from external partners of APPLICATE's information, applications that went from research, to policy making, and to operational purposes and studies. One final question asked to briefly explain how the information acquired from APPLICATE was applied in any of the above-mentioned fields.

In total, 63 people took part in the survey. The results of this questionnaire highlight that the majority of the respondents did not know about APPLICATE's KT efforts and that the KT activities with which people were most familiar are those involving the project's researchers, i.e., research publications and presentations. Moreover, according to the responses, the knowledge disseminated through APPLICATE's KT channels has been applied mostly to other research efforts, followed by business applications, as graphically summarized in Fig. 4.

When asked about the purposes of the applications of APPLICATE's information, most of the answers referred to the implementation of data or results from the project to answer different research questions, to guide operational developments and needs to inform and contribute to the future research programs. Moreover, many respondents declared to have used APPLICATE's KT materials in their own outreach efforts and to interact with policy.

Monitoring the trends and performance of online platforms and activities, documents, events, and collaborations is helpful not only for assessing the ultimate results of these activities, but it is also fundamental for evaluating whether the tools and strategies used for KT are adequate and fit with the overall purpose of the dissemination plan and the project itself. It is helpful for establishing an internal calendar to control the quantitative analytics and therefore assessing the numerical performance of the activities. In the case of APPLICATE, the project has been asked to complete three periodic reports, which were sent to the project officer at the European Commission as well as to two external reviewers. The reporting periods, which happened in intervals of 18 months from one another, provided a good occasion to run a general check on KT efforts, looking at, e.g., the evolution in the number of followers on Twitter, the new events and documents developed since the last report, the results achieved compared to the plan, and the grant agreement. Additional occasions for review have also been presentations and internal evaluation documents where the project and its work had to be outlined, happening once or twice a year. The benchmarks used to compare the performances were the measurements from previous recordings and figures from the project itself, given that the dissemination plan did not include either quantitative or qualitative objectives against which to analyze the activities. As will be seen, this has been a setback in accurately measuring the impact of KT within APPLICATE.

APPLICATE's methodology to develop and monitor its KT strategy was based on common practices implemented by the H2020 community as well as on requirements and recommendations coming from the funding agency, the European Commission (European Commission, 2015). This paper has been developed based on the experience of one single project, following the necessity to set a reference for future discussions and practices related to KT and scientific research. In this section, we will present what have been the strongest and weakest points in our implementation of the methodology described in the previous paragraphs, the lessons learned from the project, and some recommendations for other project and communication managers dealing with KT in their projects.

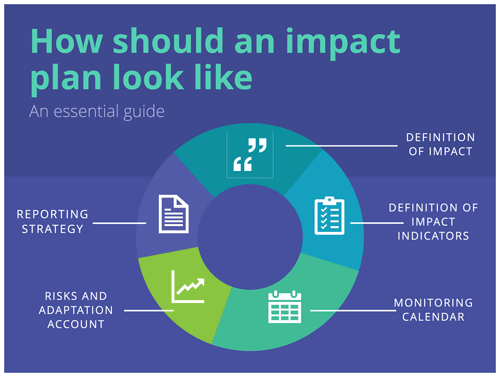

6.1 Clear goals go a long way

Each project, however similar to others, has its own, unique set of objectives and purposes. Similarly, impact can be measured differently according to the project's ultimate goals. For this purpose, it is recommendable to start developing an impact strategy at the beginning of the project outlining clear definitions for what is meant by and how to measure impact, setting clear impact indicators. As clearly put in Jensen (2014), “Good impact evaluation requires upstream planning and clear objectives from practitioners”, and the outcomes of this evaluation “should inform science communication practice”. One risk when developing and using an impact tracking strategy is to end up with a set of quantitative and qualitative information that may mean little by itself. Are 400 followers on Twitter half-way into the project a good number, or are two case studies too little? Measurements and assessments acquire more meaning when related to a standard. This standard can be an external factor, for example, common practices and measures from the funding agencies or a comparison with similarly organized projects, or it could be an internal scale, such as objectives outlined in the project's dissemination plan. When developing an impact plan for a research project, it is important to include some practical objectives to work as a benchmark for evaluating the performance of the initiative's KT efforts, as outlined in Fig. 5. This way, quantitative analytics assume a clearer value: to expand on the Twitter example, 400 followers might indicate a successful strategy if the plan is expected to reach ±50 profiles, but it might indicate a less strong impact if the team foresaw approaching 1000 individuals on that platform. For APPLICATE, a set of clear objectives was not set up in the first draft of the Dissemination Plan, thus making it harder to evaluate the development of the KT strategies throughout the project.

It is also important to underline, as mentioned, that some aspects of a KT strategy cannot be evaluated in a quantitative manner and might and therefore be less obvious and more challenging to measure. Depending on the project's idea of impact and impact objectives, each KT activity should actively contribute to the overall dissemination impact and serve a specific purpose, thereby describing how these actions fit into the overall strategy, to which target they aim, and what scenario would be considered an impactful result key to monitoring and evaluating KT efforts.

6.2 Monitoring as the first step to reaching the goal

The natural structure of any European project, such as APPLICATE, requires periodic assessments of the progress made by the team, including dissemination activities. This structure, in combination with an agile project management approach (Cristini and Walter, 2019), was instrumental in following on the development and performance of the KT activities in APPLICATE with regularity and constance to foresee possible issues and to act timely on them. In the case of online outreach campaigns, monitoring the development on a regular basis allowed the team to make internal evaluations of the individual activities, highlighting patterns (when and to whom is it best to address the campaigns) and correcting practices. This is crucial to be able to change or adapt the strategy to meet the objectives of the communication plan and to avoid reaching the end of reporting periods or the project itself with unaccomplished goals.

6.3 Involving researchers

Most of these tracking methods described in this paper require the involvement of project partners, and leaving the planning and implementation of an impact strategy to the management or dissemination team may be not only an organizational burden, but also a strategic misstep. In the experience of the APPLICATE project, the involvement of project partners in tracking and evaluating KT activities has been fundamental. Particularly with respect to scientific publications and conference proceedings, the active participation of each scientist in maintaining the internal tracking instruments such as the project's Zenodo archive and the table of dissemination and outreach activities allowed for a comprehensive and exhaustive assessment of the project's dissemination reach. Involving each project partner in all stages of the development of an impact plan is key to elaborating a strategic plan truly tailored to the needs and the capacities of a project.

6.4 The best comparison is with oneself

When developing an internal toolbox for the assessment of APPLICATE KT's impact, the project's team considered comparing some chosen indicators like the number of publications and citations and the size of the social media following with those of similarly structured projects. While a project-to-project comparison could provide a seemingly objective benchmark to evaluate one's performance, we argue this is still a partial assessment of a project's impact. As mentioned, the impact evaluation strategy of each project can (and should) take into account different aspects, which might differ greatly between two initiatives even if they are conceived around similar foundations, topics, or purposes. Two projects working to understand similar topics might want to address their impact in different ways; e.g., one could be interested in expanding the community of researchers dealing with the topic and direct its KT towards clustering a new network of research, while the other could invest in influencing the development of new policy and research programs. For this reason, we also recommend developing internal benchmarks of impact assessment and comparing the performance of KT activities with these values.

In this paper, we summarized the efforts carried out within the APPLICATE project to disseminate and transfer knowledge on weather and climate modeling in the Arctic and mid latitudes along with the strategy developed by the project management and communication team to measure the impact of its KT efforts during the project's lifetime. Developing an impact plan for communication, dissemination, stakeholder engagement, training, and clustering activities is a required, important step in the reporting process of a research project, but, as we argue in this paper, it is an essential instrument to frame the whole KT strategy of an initiative, helps to set clear objectives, and gives direction to the actions undertaken in this framework.

The methodology presented here, albeit with some limitations as highlighted in the previous discussion, has proven itself very helpful for keeping track of the team's efforts in KT, monitoring the evolution of APPLICATE's activities towards the fulfillment of the overall goals, and being able to respond and adjust the strategy when this was not the case. In particular, the instruments and approaches described here were developed following the project's needs and capacities and were adequate in providing the required insights into the funding agency during the reporting phases. What the experience with the APPLICATE project taught us is, above everything else, the importance of defining clear goals and indicators for impact assessment during the initial phase of developing a project's KT strategy, setting monitoring and reporting time frames, and involving the consortium in KT endeavors and tracking.

Although we argue in the previous paragraph against comparing the performance of different projects when it comes to KT results and activities, future actions from the funding agencies should include the development of a common set of criteria to help project officers and managers to set up an adequate impact assessment plan for their projects that comprehensively reflects not only the ambitions of their members, but also the capacities of the team and the objectives of the research program. In particular, the implementation of a monitoring strategy that captures the impact of a project beyond its lifetime is highly valuable and urgent. In addition, project and communication managers should try to develop best practices within their community, for example, by sharing lessons learned in their projects through publications and presentations at conferences and events.

Sources describing the dissemination and communication efforts in the APPLICATE project can be retrieved on the project's page on the online repository Zenodo https://zenodo.org/communities/applicate/?page=1&size=20 (last access: 7 February 2022, APPLICATE Repository, 2020), or go to the project's website: https://applicate-h2020.eu/ (last access: 7 February 2022; APPLICATE, 2021).

SP summarized the introductory section, the impact tracking methods in Sect. 4, and the discussion and conclusions. SP produced the graphics presented in this paper (Fig. 2 data and data visualization have been provided by the Barcelona Supercomputing Center and only adapted to the layout). LC led the writing of Sects. 2 and 3. TJ proofread the whole paper.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors are grateful for the valuable contributions of Dragana Bojovic, Marta Terrado (both Barcelona Supercomputing Center), and Kirstin Werner (Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research) for their friendly reviews during the preparation phase as well as the useful suggestions in making this work better. The data and data visualization for Fig. 2 of this paper have been provided by Marta Terrado and Dragana Bojovic.

This research has been supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant no. 727862).

This paper was edited by Stephanie Zihms and reviewed by Alexey Pavlov and Carmen Boening.

APPLICATE (Advanced Prediction in Polar regions and beyond: modelling, observing system design and LInkages associated with a Changing Arctic climaTE): https://applicate-h2020.eu (last access: 18 March 2022), 2021. a

APPLICATE Repository: Advanced prediction in polar regions and beyond: Modelling, Observing System Design and linkages associated with arctic climate change, Zenodo, CERN, https://zenodo.org/communities/applicate/?page=1&size=20 (last access: 18 March 2022), 2018. a

Bauer, P., Sandu, I., Magnusson, L., Mladek, R., and Fuentes, M.: ECMWF global coupled atmosphere, ocean and sea-ice dataset for the Year of Polar Prediction 2017–2020, Scientific Data, 7, 427, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00765-y, 2020. a

Blockley, E. W. and Peterson, K. A.: Improving Met Office seasonal predictions of Arctic sea ice using assimilation of CryoSat-2 thickness, The Cryosphere, 12, 3419–3438, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-3419-2018, 2018. a

Bojovic, D., Terrado, M., Johannsson, H., Fugmann, G., and Cristini, L.: User Engagement Plan, Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5035997, 2019. a

Bojovic, D., St. Clair, A. L., Christel, I., Terrado, M., Stanzel, P., Gonzalez, P., and Palin, E. J.: Engagement, involvement and empowerment: Three realms of a coproduction framework for climate services, Global Environ. Chang., 68, 102271, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102271, 2021. a

Cristini, L. and Walter, S.: Preface: Implementing project management principles in geosciences, Adv. Geosci., 46, 21–23, https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-46-21-2019, 2019. a

European Commission: Horizon 2020 indicators. Assessing the results and impact of Horizon, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020//en/news/horizon-2020-indicators-assessing-results-and-impact-horizon (last access: 3 June 2021), 2015. a, b

Findler, F., Schönherr, N., Lozano, R., and Stacherl, B.: Assessing the Impacts of Higher Education Institutions on Sustainable Development—An Analysis of Tools and Indicators, Sustainability, 11, 59, https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010059, 2019. a, b

Fugmann, G., Schneider, A., Bojovic, D., Terrado, M., Johannsson, H., and Cristini, L.: Training Plan, Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5036001, 2019. a

Gößling, H.: Welcome to Polar Prediction Matters, Helmholtz Blogs, https://blogs.helmholtz.de/polarpredictionmatters/2017/09/welcome-to-polar-prediction-matters/ (last access: 7 February 2022), 2017. a

Hewitt, C. D., Stone, R. C., and Tait, A. B.: Improving the use of climate information in decision-making, Nat. Clim. Change, 7, 614–616, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3378, 2017. a, b, c

Hill, B., Bradley, D., and Williams, E.: Evaluation of knowledge transfer; conceptual and practical problems of impact assessment of Farming Connect in Wales, J. Rural Stud., 49, 41–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.11.003, 2017. a

Jensen, E.: The problems with science communication evaluation, Journal of Science Communication, 13, C04, https://doi.org/10.22323/2.13010304, 2014. a

Johannsson, H., Bojovic, D., Terrado, M., Cristini, L., and Pasqualetto, S.: Communication and Dissemination Plan, Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5035988, 2019. a

Jung, T., Gordon, N. D., Bauer, P., Bromwich, D. H., Chevallier, M., Day, J. J., Dawson, J., Doblas-Reyes, F., Fairall, C., Goessling, H. F., Holland, M., Inoue, J., Iversen, T., Klebe, S., Lemke, P., Losch, M., Makshtas, A., Mills, B., Nurmi, P., Perovich, D., Reid, P., Renfrew, I. A., Smith, G., Svensson, G., Tolstykh, M., and Yang, Q.: Advancing Polar Prediction Capabilities on Daily to Seasonal Time Scales, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 97, 1631–1647, https://doi.org/10.1175/bams-d-14-00246.1, 2016. a

Jung, T., Day, J., and Cristini, L.: Clustering Plan, Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5036011, 2019. a

Keen, A., Blockley, E., Bailey, D. A., Boldingh Debernard, J., Bushuk, M., Delhaye, S., Docquier, D., Feltham, D., Massonnet, F., O'Farrell, S., Ponsoni, L., Rodriguez, J. M., Schroeder, D., Swart, N., Toyoda, T., Tsujino, H., Vancoppenolle, M., and Wyser, K.: An inter-comparison of the mass budget of the Arctic sea ice in CMIP6 models, The Cryosphere, 15, 951–982, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-15-951-2021, 2021. a

Lawrence, H., Bormann, N., Sandu, I., Day, J., Farnan, J., and Bauer, P.: Use and impact of Arctic observations in the ECMWF Numerical Weather Prediction system, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 145, 3432–3454, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3628, 2019. a

Lövbrand, E.: Co-producing European climate science and policy: a cautionary note on the making of useful knowledge, Sci. Publ. Policy, 38, 225–236, https://doi.org/10.3152/030234211X12924093660516, 2011. a

Morton, S.: Progressing research impact assessment: A ‘contributions’ approach, Res. Evaluat., 24, 405–419, https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv016, 2015. a, b

Notz, D. and SIMIP Community: Arctic Sea Ice in CMIP6, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2019GL086749, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086749, 2020. a

Notz, D., Jahn, A., Holland, M., Hunke, E., Massonnet, F., Stroeve, J., Tremblay, B., and Vancoppenolle, M.: The CMIP6 Sea-Ice Model Intercomparison Project (SIMIP): understanding sea ice through climate-model simulations, Geosci. Model Dev., 9, 3427–3446, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-3427-2016, 2016. a

Octenjak, S., Bojović, D., Terrado, M., Cvijanović, I., Magnusson, L., and Vitolo, C.: Is Alaska Prepared For Extreme Wildfires?, https://blogs.helmholtz.de/polarpredictionmatters/2020/11/is-alaska-prepared-for-extreme-wildfires/, (last access: 7 February 2022), 2020. a

Ponsoni, L., Massonnet, F., Docquier, D., Van Achter, G., and Fichefet, T.: Statistical predictability of the Arctic sea ice volume anomaly: identifying predictors and optimal sampling locations, The Cryosphere, 14, 2409–2428, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-14-2409-2020, 2020. a

Ross, J.: Risks and Reward: Assessing the Ocean Risks Associated with a Reducing Greenland Ice Sheet, Helmholtz Blogs, https://blogs.helmholtz.de/polarpredictionmatters/2020/05/risks-and-reward-assessing-the-ocean-risks-associated-with- a-reducing-greenland-ice-sheet/ (last access: 7 February 2022), 2020. a

Rowe, N. and Ilic, D.: What impact do posters have on academic knowledge transfer? A pilot survey on author attitudes and experiences, BMC Med. Educ., 9, 71, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-9-71, 2009. a

Schneider, A. and Fugmann, G.: Assessment of early career researcher training activities, Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4906338, 2020. a, b

Smith, D. M., Screen, J. A., Deser, C., Cohen, J., Fyfe, J. C., García-Serrano, J., Jung, T., Kattsov, V., Matei, D., Msadek, R., Peings, Y., Sigmond, M., Ukita, J., Yoon, J.-H., and Zhang, X.: The Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP) contribution to CMIP6: investigating the causes and consequences of polar amplification, Geosci. Model Dev., 12, 1139–1164, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-1139-2019, 2019. a, b

Terrado, M., Bojovic, D., Ponsoni, L., Massonnet, F., Sandu, I., Pasqualetto, S., and Jung, T.: Strategic placement of in-situ sampling sites to monitor Arctic sea ice, Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4987352, 2021. a

Tummon, F., Day, J., and Svensson, G.: Training Early-Career Polar Weather and Climate Researchers, Eos, 99, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018eo103475, 2018. a

University of Cambridge: What is knowledge transfer?, https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/what-is-knowledge-transfer (last access: 29 June 2021), 2009. a

Upton, S., Vallance, P., and Goddard, J.: From outcomes to process: evidence for a new approach to research impact assessment, Res. Evaluat., 23, 352–365, https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvu021, 2014. a

https://applicate-h2020.eu/ (last access: 7 February 2022)

https://blogs.helmholtz.de/polarpredictionmatters/ (last access: 7 February 2022)

- Abstract

- Introduction

- APPLICATE key messages

- Knowledge transfer activities

- Impact tracking

- Monitoring and reporting impact for the APPLICATE project

- Discussion

- Conclusions and recommendations

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- APPLICATE key messages

- Knowledge transfer activities

- Impact tracking

- Monitoring and reporting impact for the APPLICATE project

- Discussion

- Conclusions and recommendations

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References