the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Forum theatre as a tool for unveiling gender issues in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) working environments

Susanne Taina Ramalho Maciel

Caroline Siqueira Gomide

Thatianny Alves de Lima Silva

Gustavo Braga Alcântara

Cynara Kern

Elisabeth Andreoli

Lyvian Senna

Leandro de Oliveira Evangelista

Gender affects all aspects of life, and the working and learning environments of science, technology, engineering and geosciences present no exception. Gender issues concerning the access, permanence and ascension of women in exact sciences and Earth sciences careers in general are related to a variety of causes. The underrepresentation of women in science communications, sexual or moral harassment caused by professors and colleagues during undergraduate and graduate ages or the overloading of girls, when compared to boys, with housework during early school ages are some examples mentioned in the literature. In other words, the gender imbalance in science and technology careers may be seen as the result of a series of structured oppression suffered by women of all ages. In this context, we propose the development of an education package that is designed to understand these processes at different levels. One of the tools of this package is known as the “Theatre of the Oppressed”. Elaborated on by Augusto Boal in the 1970s, the Theatre of the Oppressed uses theatre techniques as a means of promoting social and political changes. Usually, a scene takes place that reveals a situation of oppression. The audience become what is called “spect-actors”, where they become active by exploring, showing and transforming the reality in which they are living. In the context of gender issues in exact sciences careers, the students can stage situations that reveal the subtle actions of power relations that usually put women in subservient positions. Our experience showed that, even though the acting is based on fiction, the spectators learn a great deal from the enactment because the simulation of real-life situations, problems and solutions stimulates the practice of resisting oppression in reality from within a setting that offers a safe space to practise making a change.

- Article

(1029 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The academic and pedagogical scenarios related to STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fields still present asymmetries when observing gender issues. Science represents a field of disputes in which different axes of subordination intertwine (Crenshaw, 1991; Minella, 2013), and the experiences of subjects termed women are distinct from those experienced by subjects termed men. Studies that highlighted the theme of gender and science in Brazil began in the mid-1970s with the second feminist wave. The relevance attributed to this theme was made remarkable in 1990, when de Melo and Oliveira (2006) pointed out the absence of women throughout the history of science in the country. Currently, research and actions related to gender and STEM have the collaboration of different institutions (academia, government, non-governmental organisations and spaces of formal education) to problematise, analyse and propose actions that can restructure and assign new meanings to science.

STEM fields, in particular the geosciences, are relevant fields in the environment and economy, from local to global scales, from which research results may affect a variety of bodies and lives. But, in contrast, STEM fields are some of the least diverse fields (Holmes, 2008; Nentwich, 2010; Marín-Spiotta et al., 2020). To better understand the existing asymmetries within important science disciplines related to gender, one might refer to issues regarding the distinctions between taste and learning throughout basic education, the insertion of women in science courses, persistence in academia and the professional advancement of men and women.

The worldwide scenario analysed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2017) highlights significant advances in girls' participation in education, with emphasis on higher education. In assessing the presence and permanence of girls in primary education, and despite increased access in many contexts, socioeconomic and cultural barriers still make it difficult or impossible for female students to complete and benefit fully from the good educational quality of their choice. During primary education, when children are already exposed to science and mathematics content, gender role stereotypes are already present (Leslie et al., 2015; Dickhäuser and Meyer, 2006). Teachers report that, in evaluations, they have different expectations regarding learning in science and mathematics for girls and boys (Dickhäuser and Meyer, 2006). The boundaries imposed by stereotypes are widened during adolescence, when gender roles become more entrenched for girls, including domestic and care responsibilities, the possibility of early marriage and pregnancy and cultural norms that prioritise boys' education. These boundaries result in higher rates of girls losing interest in STEM subjects with age (UNESCO, 2017; Hewlett et al., 2008).

When analysing the situation with respect to adults, women leave the STEM sector at much higher rates than men. Women represent 30 % of researchers in STEM around the world, despite being 53 % of the world's bachelor's and master's graduates in the field. This gap varies from country to country due to different sociocultural facts (UNESCO, 2017). The leaky pipeline phenomenon (see below for more detail) in STEM careers represents a waste of social investment and individual effort and suggests that there are structural problems around this scenario. The gender gap in STEM fields is undoubtedly a complex issue, especially when considering intersectionality aspects such as race, class or global-scale cultural variations (Crenshaw, 1991). These data, while considering the specificities of each country and region, still show the persistence of a pattern – men are destined for areas popularly known as challenging or difficult within STEM. The entrance and perseverance of women in geosciences are permeated by multiple symbolic references that, implicit or not, mark the limits of how far it is possible to go within the power structure represented by science.

The underrepresentation of girls and women in STEM fields is a complex (Reinking and Martin, 2018) and worldwide phenomenon (Stoet and Geary, 2018). The subject is divided into vertical and horizontal aspects, where vertical refers to the steps in career advancement, while horizontal aspects represent the societal structural constructions. Vertical segregation is usually represented by some metaphors, such as the leaky pipeline (Lima, 2013; Grogan, 2019), which depict women passively leaking out of STEM careers, revealing a waste of feminine potential and public resources. Another famous metaphor is the scissors diagram (Neugebauer, 2006), which is a plot of the percentage of men and women holding predoctoral, postdoctoral, junior group leader and professor positions. In most countries, this diagram shows a steady decline in the number of women as career stages advance, while the corresponding curve for men arises. The intersection between the lines generates a figure similar to a pair of scissors, which refers to the effect of women being cut out of STEM careers. Finally, the glass ceiling, (Rosser, 2004; Amon, 2017) or crystal maze (Lima, 2013), metaphor refers to the specific obstacles faced by women along their career paths. Lima (2013) argues that the image of the maze marks the diverse and multiple barriers along the female trajectory, and the crystal transparency refers us to the obstacles faced by these women that, at least in Brazil, are not formal but exist.

The literature on the causalities of the STEM gender gap today is large and growing. Well-known issues that constrain women's participation in science, such as housekeeping and motherhood, are largely documented. An interesting study from Abouzahr et al. (2017) showed that having children does not make women less ambitious with respect to career achievements. Instead, they demonstrated that women start their careers with as much (or more) ambition as men, but an ambition gap occurs when women work in companies where employees of both genders report low progress in diversity values. More and more research reveals that the subtle ways of privileging a certain body in a devaluation of another make up an important structure of the gender imbalance scenario. Women are also less likely to receive prizes and awards and are invited less to conferences (Holmes et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2019; Holmes et al., 2020). Besides, King et al. (2018) have shown that women and other minorities often experience a feeling of not belonging when attending scientific conferences, due to the accumulation of largely subtle behaviour and interactions during their talks and due to an established behaviour code that often privileges white researchers and men. In the geosciences, the fieldwork culture usually extols masculine strength and resistance (Carey et al., 2016), and it is not uncommon to find a lack of infrastructure for women on ships or suitable accommodation for women during field trips (Holmes, 2008), which promotes a feeling of being unwelcome. Chilly climates are frequently reported in some departments and institutions (Holmes, 2008; Amon, 2017; Marín-Spiotta et al., 2020). In trajectories analysed by physics students, for example, they emphasised the solitary path within the academic life (Lima, 2013), and Amon (2017) highlights the importance of spaces for socialisation among women.

It is a common sense in the literature that education is crucial for reducing gender inequality, but the strategies may vary. We consider that an emphasis on reducing the gender gap in strategic areas, such as geoscience courses, is crucial. The gender gap is measured globally by the World Economic Forum in the following four key areas: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival and political empowerment (World Economic Forum, 2020). According to the 2020 Global Gender Gap index (Black, 2020), it will take us nearly 100 years to achieve gender parity. Today, 55 % of working-age women are in the labour market, against 78 % of men. This gap has been narrowed in the last decades, and having more women exerting economic activities outside the home usually translates into improved health, reduced domestic violence for girls and women and more significant economic growth for the society as a whole. But, according to the World Economic Forum's report (World Economic Forum, 2020), if we consider the fastest-growing professions of the future, critical data reveal the following problematic situation: women represent only 26 % of people with artificial intelligence and data skills, 15 % of people with engineering skills and 12 % of those with cloud computing skills. The inclusion of young girls in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) courses is thus an important key for embedding gender parity and preventing a setback in women's access to the labour market.

While some works show that there are no gender differences between girls' and boys' skills in mathematics (Kersey et al., 2018), it is widely investigated that girls and women are more concerned than boys about their teachers, parents and mentors evaluation (Aiken and Dreger, 1957; Dickhäuser and Meyer, 2006; Ginther and Kahn, 2015). Some elements can influence the permanence of women in STEM courses, including the inspiration and support of close and influential people such as family members and teachers (de Amorim et al., 2017). By staying on the chosen academic path, the construction of the career is also permeated by systems of oppression and power (Marín-Spiotta et al., 2020). Factors that influence women's permanence in careers in STEM include the compatibility that is perceived between specific STEM fields with female identity, compatibility with family obligations and compatibility with the environment and working conditions. In short, it seems settled that subtle issues and structured behaviours matter concerning gender gaps in the STEM field.

On the other hand, it is not straightforward to deal with emotional aspects, such as low self-esteem or pointing out a particular behaviour. According to Renki (2018), communicating to someone that they are sexist usually does not work. Besides, there are multiple ways to stereotype different social groups, and tracing how someone is treated based on particular characteristics is a tricky task.

Bleuer et al. (2018) argue that the capacity of the theatre to capture and communicate relational aspects is beneficial for knowledge mobilisation. From a psychological point of view, theatre enables audience members to cultivate greater empathy for the issues witnessed on the stage. The usage of verbal and nonverbal communication allows a level of engagement with the cognitive and emotional aspects of the audience, which promotes the perfect environment for understanding the complex dynamics that permeate gender issues in academia. Forum theatre (Boal and McBride, 2013) is historically used by social movements. Still, it is also being used by researchers and policymakers to communicate science and to discuss problems in a contextualised way (Burgoyne et al., 2007; Shanley and López, 2009; Strickert and Bradford, 2015). In particular, theatre is an incredible tool for gender issues in science mobilisation. Taking into account that, beyond explicit violence and harassment against women, subtle violence (and legal violent acts) is understood with empathy through theatrical shows, which does not necessarily happen through direct presentations or reports.

The present study applies a method designed to promote a positive environment towards gender diversity in the various contexts that permeate the university, including the access and permanence of graduate and undergraduate students, the gender-biased relations between professors, students and technicians and the superior management policies. We adapted an arts-based mobilisation tool to educational contexts to overcome self-expression barriers and focused on a highly diverse public, including high school students from public schools, natural sciences students from the University of Brasília, professors and researchers. We perceived that political theatre, in combination with mainstream communication strategies, has the capacity to attract the attention of the university top management to gender issues within all the discussed sectors. As per the following list, the goals of this article, then, are to describe one method of:

-

communicating about university access among different groups by focusing on gender issues;

-

bringing gender issues discussions into the university community (faculty, staff and students) while avoiding direct conflicts;

-

publicising the work of female scientists; and

-

providing a safe place to promote discussions and to empower female students.

We will present the results from the actions promoted in the implementation of an extension project at the University of Brasília. Our analysis is based on qualitative methods for assessing the interactive and political theatre performance's impact. This work has practical implications for companies, schools and universities managers and research coordinators by describing a project that aims to foster gender parity by promoting self-understanding, revealing social structures and unveiling myths.

The University of Brasília is the fourth most prominent university in Brazil (LLC, 2015), and its resources are distributed between four campuses. The Planaltina Campus (FUP) was implemented before the federal government's higher education expansion programme. The Planaltina Campus corresponds to the region that aggregates Planaltina, Sobradinho, Brazlândia, Sobradinho II, Formosa, Buritis, Cabeceiras, Planaltina de Goiás, Vila Boa and Água Fria de Goiás, and it was officially inaugurated on 16 May 2006, with 70 students enrolled in the Natural Sciences Licensing and Bachelor of Agribusiness Management courses, with 10 doctoral professors.

FUP has existed for almost 15 years, having being conceived in a plan of decentralisation of the university infrastructure. The campus is situated 40 km away from the main campus, in a city of a mainly low-income population, and is surrounded by rural areas, including large estates and smallholdings. The city's economy is based on agriculture, and therefore, most of the jobs offered in the region are in some way linked to agribusiness management. This fact led to the opening of four undergraduate courses, namely natural sciences licensing, peasant education, agribusiness and agroecology management, which are somehow related to earth sciences and in which at least an introduction to geosciences is offered regularly as a mandatory course. Together, these courses today provide 420 annual chairs for higher education, including diurnal, nocturnal and full-time courses. The campus also houses seven graduate courses, including Environmental Sciences (master's and doctoral degrees), Materials Science, Science Teaching, Public Management, Water Resources Management and Regulation, Environment and Rural Development and Sustainability with Traditional Peoples and Territories (master's degree).

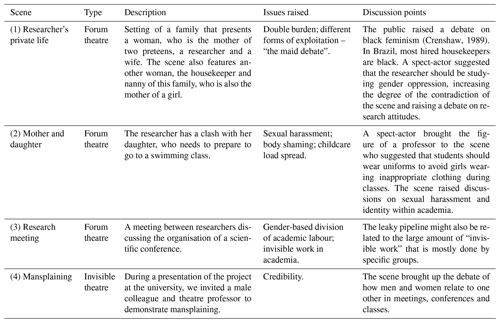

Table 1Proportion of male and female entrance and graduation at Planaltina campus, divided as follows for each undergraduate course: natural sciences licensing daytime (CNN) and nighttime (CND), teaching degree in peasant education (LEDOC), environmental management (GAM) and agribusiness management (GEAGRO).

According to data extracted at the beginning of 2020, we can see that the Planaltina campus follows the gender gap found in the literature from data on student enrolment and graduation in all courses. Table 1 shows that in three courses offered at FUP – natural sciences licensing daytime (CNN) and nighttime (CND), and the teaching degree in peasant education (LEDOC) – the entry of female students is higher. These courses are degree courses for teacher training, which is a profession usually attached to women. Therefore, the enrolment of 54 % women is expected. In the other two courses, environmental management (GAM) and agribusiness management (GEAGRO), we observe a slight male dominance at the enrolment and a reversal of the pattern for graduation rates. Women are the ones who graduate most in all FUP courses, with a total of 60.3 %, but in the peasant education course it reaches 69.8 %, and in the courses with the highest number of men, the index graduation rates for women reaches 56.9 % and 52.9 %, increasing the proportionality with the entrance and raising the total graduation rate. The economic reports, though, show that these women do not achieve visibility, even with higher graduation rates.

These data follow the studies made by Pereira and Favaro (2015), who affirms that women are the majority at all education levels in Brazil, including undergraduate levels. Even though the courses in which there is a dominance of women are those considered as being studies that are typically for females, they are, in total, still the majority. Guedes (2008) did a study on the female presence in university graduate and undergraduate courses. She affirms that an analysis of the last IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) census studies reveals that, in 30 years, women succeeded in reversing the historical inequality and consolidated a new reality in which they are the majority (60 %) of the graduates among the youngest, which is consistent with Planaltina Campus numbers.

The Brazilian Federal Constitution states that the university is characterised by the inseparability of teaching, research and extension. Here, we refer to the university extension as an interdisciplinary, educational, cultural, scientific and political process that promotes transformative interactions between the university and other sectors of society. Through extension actions, it is possible to promote social inclusion and to promote a wider dissemination of knowledge.

Planaltina Campus is the campus that is the most engaged with the population that surrounds the university. It has more than 60 extension projects and programmes, led by campus professors, staff and students, which promote social activities, engaging the population and academia research. Of those, at least three projects use political theatre as a tool to disseminate research findings, organise groups and capture and communicate knowledge about social relationships. The Terra em Cena programme is one of FUP's extension programmes to promote articulated actions between teaching, extension and research (Boas et al., 2019). The programme has existed since 2010 with the scope of theatrical and audiovisual language, working mainly with students from the Peasant Education course. Thus, all the participants of the programme are deeply involved with peasant communities and settlements, often linked to social movements, or are part of the Kalunga Quilombola territory (Gomide et al., 2019).

The present work describes the results achieved with the project “Mulheres cientistas: desafios, mitos e resistência cotidiana” (“Women in science: challenges, myths and daily resistance”). The project has existed since the beginning of 2019 and is focused on teaching and communicating activities. In this manner, we offer a set of laboratory routines for high school students, with activities based on women's work, to promote representativeness and to rescue the hidden figures of science history. The project also facilitates a regular study group that asks the participants to think about data, structural issues and to study feminist texts. And finally, we invite the public to feel how a scientist feels, how a woman feels and how relations are posed, using strategies from popular theatre. The theatre-based activities are co-conducted with the extension programme of Terra em Cena.

Part of Terra em Cena's activities involve action in the Brazilian capital which is equivalent to what is being done in the capitals of Argentina and Uruguay. The orientation of the International Network of Theatre and Society (Boas et al., 2019) is to open new training schools in political, audiovisual and arts settings and to offer political formation in the countryside and the city that is articulated with social movements.

The provision of the politicisation of the experience through the Theatre of the Oppressed and the contact with Brazilian dramaturgy that addresses issues of interest to the rural population enables the nexus between aesthetic and political formation and the community's social organisation process. In the teaching degree programme in Peasant Education, the work of the Terra em Cena programme collaborates with programme to promote multiple literacies (Freire and Macedo, 1987) by adding linguistic studies, written literacy, grammar and literature to theatrical and audiovisual languages.

The ability of the theatre to capture and communicate knowledge about social relationships in ways that are not always possible through texts (Bleuer et al., 2018) makes the Terra em Cena programme an articulator of interdisciplinary activities.

Throughout the Terra em Cena experience, the theme of patriarchy and feminism has been one of the main topics in the theatre plays and audiovisual products of the groups that emerged from their performances. In this context, the participants of the project “Mulheres cientistas” approximated activities in the theatre that were promoted by Terra em Cena. To explain and discuss ways of demonstrating gender imbalance in its most diverse perspectives, with an emphasis on the particularities of exact and Earth sciences, we put on a set of theatrical and/or audiovisual sketches based on commonly identified situations of harassment in this environment.

The Theatre of the Oppressed is the name that Augusto Boal gave to his systematisation of theatre techniques as means of promoting social and political changes (Boal and McBride, 2013). The scenes usually aim to reveal oppression situations, and the audience participates in the scene in active ways, becoming what is called “spect-actors”. The spect-actors transform the reality in which they are living by exploring and changing the scene. A major concept of the Theatre of the Oppressed is that it is not enough to interpret the reality; it is necessary to transform it. We used two techniques from the Theatre of the Oppressed in the project, namely the invisible theatre and the forum theatre.

The invisible theatre is a form of acting in which the audience does not necessarily know that a scene is taking place. It is possible to present an invisible show anywhere where the drama could really happen or has already occurred (for example, in a laboratory, a meeting, a conference presentation or a cafe). It is an interesting form of organisation since there are no explicit spatial (auditorium and stage) or personal (actors and audience) hierarchic configurations. The key to an invisible theatre intervention is its political effectiveness, by revealing contradictory dynamics through a scene represented with reality. To this end, it is necessary to develop the aesthetic effect of the scene.

According to Boas (2019), a successful invisible show must follow some basic rules, such as “Actors should never commit any act of violence against or intimidate spectators – their actions must always be peaceful, as they are revealing the violence of society as it exists, not duplicating it”, “the scene must be as theatrical as possible, and must be able to unfold even without the participation of the spectators” and “One should never perform an illegal act since the aim of the invisible theatre is precisely to question and challenge the legitimacy of legality”. The invisible theatre demands particular efforts in rehearsing not only the predicted scene but also any possible or predictable interventions by future spectators.

As with the invisible theatre, the forum theatre also aims to make oppression visible, but in this arrangement, the scene is explicit, and the show acts as a forum to help people understand how they can change their world. Audience members become actors in crucial moments of the proposed scene, directing the way the play reaches its climax through changes to the specific behaviour of a character or by modifying a given configuration.

In this sense, our group developed some scenes, based on the invisible theatre that are performed during public talks at the university or during our science labs with students, to reveal micro and macro sexist situations – especially in academic environments. The performances usually have a silent impact that can be noticed by a general change in the behaviour of participants and spectators, which reveals a level of empathy that stems from the scenes. We also developed forum theatre scenes, and we noticed particular challenges that come from the fact that forum theatre deals with an immediate intervention from the audience.

A known example of feminist theatre is the group led by Muriel Naessens, in France, called Féminisme-Enjeux (Ferré, 2019). What we learn from our experience and the Ferré (2019) report on Féminisme-Enjeux issues is that violence against women, especially subtle violence which is socially accepted and demonstrated in forum theatre experiences, means that it is not uncommon for the spect-actor to bring solutions to the stage based solely on the empowerment of the oppressed woman – almost as if the victim were also responsible for her own oppression. Thus, some interventions are necessary to guarantee that the concept of private violence is a public concern is well understood by all participants. In other words, the participants must be aware that only collective action, legislative innovations and public policies truly transform reality.

4.1 Creating the play

In the scope of the project “Mulheres cientistas”, we used forum or invisible theatre for each presented context. For school activities and workshops offered at the university, we used forum theatre schemes to promote particular discussions brought up by the workshop participants. We used invisible theatre in public situations at the university, such as presentations of projects to colleagues or management meetings. The scenes were elaborated on and performed by professors and students. The study groups were useful for collecting data, information and thoughts on which to base the script and predict possible reactions.

One of the ways of achieving the project's objectives is to reveal structural gender oppression, which is not necessarily directly connected to the academy but which necessarily influences academic paths. The intrinsic culture of paternalism makes it difficult to perceive harassment situations to which all women are subjected in their daily life and that can happen in a simple trip to the supermarket, during a business meeting, in a college class or a in domestic situation. The idea of portraying some scenes was to connect with these situations and reveal different scales and levels of the consequences of this social structure.

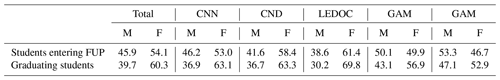

The first elaborated scene brings a setting of a family that presents a woman who is a mother of two preteens, a researcher and a wife. The scene also features another woman, the housekeeper and nanny of this family, who is also the mother of a girl.

The scene begins with the tired researcher, on a sleepless night, working on a project and dealing with two children who use their mobile phones all the time and argue tirelessly. At that time, the housekeeper arrives, but she was late because she was not able to take the transport on time due to the precarious conditions of public transportation.

At this point, the housekeeper reported that the only alternative she had to come to work after a long wait was to take crowded transport and that she felt intimidated and afraid of suffering sexual harassment on the bus, which is a common situation when the bus is crowded.

The scene continues with the housekeeper taking care of the house and dealing with the chaos with the children while the researcher finishes her project with a new cup of coffee. Then the housekeeper's daughter calls her and asks for materials for school, and she responds, saying that there is no way to buy it because she will come home late from work. The scene has the intention of showing the contradictions in the relations of these two women. They confide in each other about their difficulties at work and in life. One has spent all night working on the project that has not even finished, and the children do not rest until the housekeeper arrives and takes care of them. The housekeeper, on the other hand, is barely able to come to work because of the stress caused by the transportation in which she is likely to be harassed, and she works all day, caring for her mistress's things and children, but will not have time to take care of her own daughter's needs. It is a relationship that could, for some, be seen as a complicated relationship in which there is some complicity on the part of the researcher and the housekeeper but which, in many ways, shows contradictions.

In another part of the scene, the researcher clashes with her daughter, who needs to prepare to go to a swimming class. The mother asks her daughter to wear a more less revealing outfit because the girl is wearing shorts and a low-cut tank top and could be inadvertently inviting someone to harass her. The fight revolves around the mother wanting to protect the daughter from harassment and the daughter defending her right to dress like that because it is sweltering outside (Minella, 2013; Lima, 2013).

The second part of the scene shows the researcher talking on the phone with her husband. In the call, he says that he can pick the girl up from the swimming class that day, which makes her feels relieved and grateful that he will be able to finish the work she was doing. For a moment, within the reflection of the character, she is extremely grateful to have a good husband who helps her with her children when she needs it. In the next instant, she realises that it is actually his job to take care of the children, thus ending the first scene and starting the discussions.

The third scene features a meeting between researchers discussing the organisation of a scientific conference. In this scene, we have three female researchers and three male researchers who present themselves as invisible men (the actors are not on the scene). The scene begins with one of the female researchers reading the agenda and being constantly interrupted by one of the researchers until one colleague interferes and asks him to stop so that the other can continue.

Then meeting turns to the agenda point of discussing the role of the event coordinator. The male researchers propose a senior researcher who has coordinated previous events but is never present in any meeting, and the female researchers advocate the name of a woman who is genuinely involved with the event to coordinate it. She accepts the nomination as coordinator, suggesting that the senior researcher should be invited as support because joint work will be necessary due to her experience and network. At this point, the women in this group show how they prefer to work in a collaborative and supportive network, and they bring up a matter from the scientific committee where the men only promote other men. The last agenda item is the responsibility of the local organising committee, which none of the men present wants to coordinate. It is stated that all the women at the table have already played this role and that they are neither secretaries nor party organisers, yet the men are reluctant to take on secretarial roles or secondary activities.

Before the meeting is over, one of the invisible male researchers gets up to leave, saying he needs to pick up his son from school. Two of the women find the attitude of a good father beautiful, as he takes good care of his son, and they compliment him. The third is not moved by the scene because when a woman plays the same role, the scene is not touching and a negative judgement of her usually takes place.

These scenes, which sought to show how patriarchy affects professional roles between men and women, bring exciting discussions on why women still have to impose themselves to not always be subdued or how the system is set up so that women depend on other women to take care of their children and houses.

(Crenshaw, 1989)Another act that the “Mulheres cientistas” group performed was an invisible theatre scene. During a presentation of the project at the university, a male colleague, and theatre professor, was invited to promote the term of “mansplaining” in the recent feminist literature (Solnit, 2014), which means that a man keeps explaining what a woman has just explained as if the way she communicates in a group is not sufficiently clear. So, during the explanation of the project, the professor would continuously interrupt the talk to congratulate the project and to re-explain what was already explained. This is a prevailing situation that is often uncomfortable because it steals the limelight from the woman speaking. On the other hand, it can be very subtle oppression, since all the comments were favourable and sweet. When the scene was revealed at the end of the presentation, a big contradiction was set. The vast majority of the audience did not realise that a scene was taking place because they perceived it to be normal to have a person in the audience re-explaining the talk. A small survey after the scene revealed that only women said they felt uncomfortable with the constant interruptions. Table 2 summarises the scenes constructed and the debates raised in each piece.

4.2 Action

The study was conducted with four focus groups, composed by high school students, university students or faculty members. During the second semester of 2019, the project's female actors performed four times, using different Theatre of the Oppressed techniques. Our research instruments are documented speeches by spect-actors of the plays, photographic records and analysis by four focus groups. Some images from the performances are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1Images from the performances. (a) The scene of a mother with her children. The man in blue is a spect-actor who proposed changes to the way the others should act. (b) Theatre exercise during a workshop at Planaltina Campus. (c) Workshop at a high school. (d) An invisible theatre scene; the presenter was constantly being interrupted, and the audience was not aware that a scene was taking place. The scene was supposed to represent a common situation at the university, so we did not record the event with good quality cameras. Photographs were taken by the authors.

The first performance occurred during a workshop at the university for the public. A total of 30 people participated and were between 19 and 50 years old and comprised 40 % university rural students, 30 % university urban students and 20 % external (from the university) public participants. After a discussion about the gender imbalance in science, the workshop participants were divided into four subgroups, where each group constructed a scene. Despite the fact that the focus of the workshops was always clearly on gender imbalance in STEM, all the small groups constructed scenes about private life situations such as child care, domestic violence or gender-based division of domestic work.

The second focus group was also comprised of university students, but no workshops were offered. During that opportunity, the actresses performed the first three scenes from Table 2. Some spect-actors proposed changes to the scenes, and the proposals were mainly related to the housekeeper and researcher relationship (scene no. 1). There was an explicit discomfort with the settled structure in which a set of gender-oriented, layered oppression is imposed while a cruel class division also takes place. Once more, the private life aspects received more attention, and it was interesting to notice that the audience proposed no interferences to the meeting configuration (scene no. 3).

Our third performance was the invisible theatre scene that happened at the campus, during a public presentation, where we simulated a mansplaining situation (scene no. 4). Once again, no workshops were offered, and in this case, no direct interventions were made due to the nature of the invisible theatre. We evaluated that invisible theatre has a great potential to promote silent self-reflection in which people consider their own behaviour. Although we still do not have the means to present a quantitative result of the impact of the scene, we would like to register that the experience positively reverberated in our community. We received accounts from male professors that, after the scene, they have started to police themselves to avoid such undesirable situations. We also argue that this kind of theatre is suitable for mitigating university dropouts. To illustrate the theatre's potential in this regard, a student related to us that she decided against dropping out of the university when she realised, while watching one of the project presentations, she was “not the only girl who had the feeling that university was not designed for her, or that she should be at home, taking care of her brother”.

Finally, we promoted a workshop in a public high school, with 70 students aged 15 to 16 years old. The students were divided into seven groups, and after a discussion on gender imbalances in STEM, they proposed their sketches. This time, the sketches were centred on university access. The groups performed situations that they believed limited their admission to a public university. They created scenes about police violence in front of the school, drug dealing at school, precarious public transport, lack of suitable places to study at home and the absence of good public libraries near their houses. It was interesting to notice how different but relevant topics appeared in each time a workshop was promoted with a different public. Theatre allows personal experiences to be discussed in an organised and systematised way, without exposing intimacies. The mixture of real facts with theatrical elements makes the actor or actress feel comfortable enough to expose intimate feelings or nuisances.

Our first goal was to bring the discussion about the gender gap in STEM careers into the university. We tried two different approaches, namely promoting public talks and debates and creating a group of studies with students from three different courses. The discussions were interesting, but the activities were short and did not reverberate within the entire campus community. The idea of the study groups was to give continuity to the debates. The bibliography of the study group was vast, and the students were engaged with the theme. The most interesting part of the study group, though, happened when students brought their personal experiences into the discussion because it was at this point that the participants incorporated the debate. However, talking about personal experiences is usually delicate, and it demands a lot of time from the entire group through listening and promoting a safe place to share confidences. Thus, we noticed that we had to choose a methodology that was capable of systematising all the exposed experiences, without exposing intimacies, and that could be performed in an organised amount of time. At the same time, we wanted to propose a method that could inspire changes to the reality that was being described by the participants. The experience with political theatre from other projects, such as Terra em Cena programme, inspired us to adopt the drama into our practice. We used the data collected from the study groups to create the characters, the forum theatre components and the invisible theatre sketches.

One approach to increasing the effectiveness of forum theatre for gender issues debates would be presenting sketches in which known challenges in women's daily life are posed. These kinds of scenes appear to elicit two kinds of undesired reactions from spect-actors, namely the absence of interaction, given that the audience might not recognise themselves in the scene, or any type of intervention that suggests that the woman is responsible for her own oppression. It is common to observe that, following scenes of harassment, the interventions from spect-actors assume the place of the victim and solve the problem by reporting the harassment to someone in a position of superiority. As pointed out by Naessens, interventions should always suggest collective solutions. Focus groups in which theatre workshops took place and participants were given time to build their own scenes presented more elaborate interventions than those in which only the forum theatre was performed.

Political theatre is a source of research for identifying a series of gender inequality boosters in academia. Theatre can unveil the causes of high rates of dropouts, how students perceive gender issues in their personal lives and how several aspects of social relations affect the gender imbalance in academia. Regarding the choices of the scenes of the first focus group, our observations yielded similar results to Boal's statement in that the choices of the topics for the sketches are always related, directly or indirectly, to personal experiences. We expected, initially, that the participants would bring scenes strictly related to gender oppression in academic environments, such as sketches of moral or sexual harassment from professors, but the results showed that the theatre has the potential to deepen the understanding of a concept by connecting real data to personal experiences. The theatre experience made it clear that the gender imbalance in STEM is a socially structured topic, where bridging the gap will only happen with broad public policies for women. We also determined from the first workshop that theatre is a safe place to discuss private issues because the public never knows if the scene is based on real facts or not. In a context of high rates of dropouts and psychological disturbances among students, theatre seems to be an ideal tool to mitigate some relational challenges that are common and also mysterious at the university.

As researchers and professors, it is imperative that, while we advance in our research, we also grow in promoting equality in academic work environments within its all stages. It is clear to us that the gender imbalance in STEM careers affects not only academics but also all societal structures. Having more women studying and working in STEM areas guarantees the future of a society in which men and women have balanced job opportunities and in which technology is developed to promote the interests of both men and women. We plan to assess quantitative results of the forum theatre impact by evaluating the evolution of the perception on gender issues in the high school and university focus groups.

The data used in this work are available in the text.

STRM, CSG, TAdLS, CCKB and EA conceived and directed the project. GBA conducted science workshops and helped with the analysis of the forum theatre results. LS conducted the forum theatre workshops. LdOE helped shape the research and provided data to support forum theatre scenes. STRM, CSG and TAdLS contributed to the analysis of the results and the writing of the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article is part of the special issue “Five years of Earth sciences and art at the EGU (2015–2019)”. It is not associated with a conference.

We would like to express our very great appreciation to the groups Terra em Cena and Cia Burlesca for their valuable and constructive suggestions during the planning and development of the theatre workshops.

This paper was edited by George Sand França and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abouzahr, K., Krentz, M., Taplett, F., Tracey, C., and Tsusaka, M.: Dispelling the myths of the gender “ambition gap”, Boston Consulting Group, availabe at: http://image-src.bcg.com/Images/BCG-Dispelling-Myths-of-Gender- Ambition-Gap-Apr-2017-Revised_tcm9-150012.pdf (last access: 26 February 2021), 2017. a

Aiken, L. R. and Dreger, R. M.: the Effect of Attitudes on Performance, J. Educ. Psychol., 52, 19–24, 1957. a

Amon, M. J.: Looking through the glass ceiling: A qualitative study of STEM women's career narratives, Front. Psychol., 8, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00236, 2017. a, b, c

Black, C. F.: Global Gender Gap Report, Technical Report, World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119085621.wbefs350, 2020. a

Bleuer, J., Chin, M., and Sakamoto, I.: Why theatre-based research works? Psychological theories from behind the curtain, Qual. Res. Psychol., 15, 395–411, https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1430734, 2018. a, b

Boal, A. and McBride, C.: Theatre of the Oppressed, Theatre Communications Group, New York, ISBN 9781559367783, 2013. a, b

Boas, R. L. V.: Invisible theatre: from origins to current uses, in: The Routledge Companion to Theatre of the Oppressed, edited by: Howe, K., Boal, J., and Soeiro, J., Routledge, Abingdon, UK, 162–167, 2019. a

Boas, R. L. V., Pinto, V. C., and Rosa, S. M.: The School of Political Theater and Popular Video of Federal District: formation by praxis, Urdimento, 1, 36–47, https://doi.org/10.5965/1414573101342019036, 2019. a, b

Burgoyne, S., Placier, P., Thomas, M., Welch, S., Ruffin, C., Flores, L. Y., Celebi, E., Azizan-Gardner, N., and Miller, M.: Interactive Theater and Self-Efficacy, New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2007, 21–26, https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.282, 2007. a

Carey, M., Jackson, M., Antonello, A., and Rushing, J.: Glaciers, gender, and science: A feminist glaciology framework for global environmental change research, Prog. Hum. Geog., 40, 770–793, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515623368, 2016. a

Crenshaw, K.: Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, Univ. Chicago Leg. For., 140, 139–167, 1989. a

Crenshaw, K.: Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color, Stanford Law Rev., 43, 1241–1299, 1991. a, b

de Amorim, V., Dantas, M., and de Carvalho, M.: Estratégias De Superação Utilizadas Por Mulheres Recém-Doutoras Em Física, in: Proceedings of the Seminário Internacional Fazendo Gênero 11 and 13th Women's Worlds Congress, 30 July–4 Augst 2017, Florianópolis, Brazil, 1–11, 2017. a

de Melo, H. P. and Oliveira, A. B.: A produção científica brasileira no feminino, Cad. Pagu, 27, 301–331, https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-83332006000200012, 2006. a

Dickhäuser, O. and Meyer, W.-U.: Gender differences in young children's math ability attributions, Psychology Science, 48, 3–16, 2006. a, b, c

Ferré, G.: Féminisme-enjeux: challenges and paradoxes of a feminst Theatre of the Oppressed company, in: The Routledge Companion to Theatre of the Oppressed, edited by: Howe, K., Boal, J., and Soeiro, J., Routledge, Abingdon, UK, 375–380, 2019. a, b

Ford, H. L., Brick, C., Azmitia, M., Blaufuss, K., and Dekens, P.: Women from some minorities get too few talks, Nature, 576, 32–35, 2019. a

World Economic Forum: World Economic Forum Report, available at: http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2020/ (last access: 26 February 2021), 2020. a, b

Freire, P. and Macedo, D. P.: Literacy: reading the word and the world, Bergin and Garvey Publishers, Routledge, Abingdon, UK, 1987. a

Ginther, D. K. and Kahn, S.: Comment on “expectations of brilliance underlie gender distributions across academic disciplines”, Science, 349, pp. 391, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa9632, 2015. a

Gomide, C. S., Villas Boas, R. L., Martins, M. L., Gouveia, L. R., and Dias, A. L.: Rural Education and Pedagogy of Alternance: UnB experience in the Kalunga historical site and cultural heritage, Brazilian Scientific Journal of Rural Education, 4, 1–27, https://doi.org/10.20873/uft.rbec.e7187, 2019. a

Grogan, K. E.: How the entire scientific community can confront gender bias in the workplace, Nature Ecology and Evolution, 3, 3–6, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0747-4, 2019. a

Guedes, M.: Women’s presence in undergraduate and graduate courses: deconstructing the idea of university as a male domain, História ciências saúde, 15, 117–132, 2008. a

Hewlett, S. A., Buck Luce, C., Servon, L. J., Sherbin, L., Shiller, P., Sosnovich, E., and Sumberg, K.: The Athena Factor: Reversing the brain drain in science, engineering and technology, Harvard Business Review Research Report, Harvard Business Publishing, Boston, USA, 2008. a

Holmes, M. A.: Gender imbalance in US geoscience academia, Nat. Geosci., 9, 8–82, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo113, 2008. a, b, c

Holmes, M. A., Asher, P., Farrington, J., Fine, R., Leinen, M. S., and LeBoy, P.: Seafloor Seismometers Monitor Does Gender Bias Influence Northern Cascadia Earthquakes Awards Given by Societies?, EOS Trans. AGU, 92, 421–422, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo113, 2011. a

Holmes, M. A., Myles, L., and Schneider, B.: Diversity and equality in honours and awards programs – steps towards a fair representation of membership, Adv. Geosci., 53, 41–51, https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-53-41-2020, 2020. a

Kersey, A. J., Braham, E. J., Csumitta, K. D., Libertus, M. E., and Cantlon, J. F.: No intrinsic gender differences in children's earliest numerical abilities, npj Science of Learning, 3, 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-018-0028-7, 2018. a

King, L., MacKenzie, L., Tadaki, M., Cannon, S., McFarlane, K., Reid, D., and Koppes, M.: Diversity in geoscience: Participation, behaviour, and the division of scientific labour at a Canadian geoscience conference, Facets, 3, 415–440, https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2017-0111, 2018. a

Leslie, S.-J., Cimpian, A., Meyer, M., and Freeland, E.: Expectations of brilliance underlie gender distributions across academic disciplines, Science, 347, 262–265, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483392240.n8, 2015. a

Lima, B. S.: O labirinto de cristal: As trajetórias das cientistas na física, Revista Estudos Feministas, 21, 883–903, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-026X2013000300007, 2013. a, b, c, d, e

LLC: Portal da Transparencia, available at: http://www.portaltransparencia.gov.br/?minifiedPath=%2Fminified&projectVersion=1.16.1 (last access: 31 July 2019), 2015. a

Marín-Spiotta, E., Barnes, R. T., Berhe, A. A., Hastings, M. G., Mattheis, A., Schneider, B., and Williams, B. M.: Hostile climates are barriers to diversifying the geosciences, Adv. Geosci., 53, 117–127, https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-53-117-2020, 2020. a, b, c

Minella, L. S.: Temáticas prioritárias no campo de gênero eciências no Brasil: Raça/etnia, uma lacuna?, Cad. Pagu, 40, 95–140, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-83332013000100003, 2013. a, b

Nentwich, F. W.: Women in the geosciences in Canada and the United States: A comparative study, Geosci. Can., 37, 127–134, 2010. a

Neugebauer, K. M.: Keeping tabs on the women: Life scientists in Europe, PLoS Biol., 4, 494–496, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040097, 2006. a

Pereira, A. C. F. and Favaro, N.: História da mulher no ensino superior e suas condições atuais de acesso e permanência, Seminário Internacional sobre profissionalização docente, 6, 5527–5542, 2015. a

Reinking, A. and Martin, B.: The gender gap in STEM fields: Theories, movements, and ideas to engage girls in STEM, Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 7, 148–153, https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2018.7.271, 2018. a

Renki, M.: Opinion: How to Talk to a Racist, The New York Times, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/30/opinion/how-to-talk-to-a-racist.html, last access: 30 July 2018. a

Rosser, S. V.: The Science Glass Ceiling: Academic Women Scientist and the Struggle to Succeed, 1st edn., Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203337752, 2004. a

Shanley, P. and López, C.: Out of the loop: Why research rarely reaches policy makers and the public and what can be done, Biotropica, 41, 535–544, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7429.2009.00561.x, 2009. a

Solnit, R.: Men explain things to me, Haymarket Books, New York, USA, 2014. a

Stoet, G. and Geary, D. C.: The Gender-Equality Paradox in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Education, Psychol. Sci., 29, 581–593, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617741719, 2018. a

Strickert, G. E. H. and Bradford, L. E. A.: Of Research Pings and Ping-Pong Balls: the use of forum theater for engaged water security research, Int. J. Qual. Meth., 14, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915621409, 2015. a

UNESCO: Measuring Gender Equality in Science and Engineering: the SAGA Toolkit – Working Paper 2, Technical Repoty, UNESCO, Paris, France, available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0025/002597/259766e.pdf (last access: 26 February 2021), 2017. a, b, c