the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Students' sense of belonging and its impact on effectively teaching about environmental changes in high latitudes during a master's programme

Karoliina Särkelä

Janne J. Salovaara

Veli-Matti Vesterinen

Joula Siponen

Katariina Salmela-Aro

Laura Riuttanen

Katja Anniina Lauri

Sense of belonging plays a significant role in students' academic success. For the “Environmental Changes at Higher Latitudes” master's programme, success is effectively communicating geoscience research and ideas to the students. This study explores students' perceived sense of belonging, the conditions for belonging among master's students of this particular programme, and the impact of belonging on educational effectiveness in a climate change context. This programme is organised jointly between universities of three Nordic nations and for it – and for the multilocality of the geoscience themes – has a particularly high degree of mobility. Therefore, the programme lacks elements present in a typical higher education experience, such as on-site attendance in a physically shared space with a relatively stable group of peers and instructors which are thought significant for the students' feelings of belongingness. Based on 15 interviews, we elaborate on the findings of the students' motivation, ability and opportunities to belong and on the construct of their perceived belonging. Emerging from this study, these constructs for sense of belonging consist of the students' sense of familiarity – familiar elements in the place, surroundings and culture; sense of recognition – recognised by oneself and others as a peer and a member of the knowledge community; and last, sense of relevance – finding their studies relevant and interesting. Due to the unique set-up of the programme, the study reveals insight into elements that support the sense of belonging, crucial especially in such geoscience and climate education and communication that might lack the typical shared physical space of a programme, but applicable to curriculum design and development of any programme with high degree of mobility.

- Article

(2977 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Environmental changes and the discourse surrounding climate change have become ubiquitous in global society (e.g., Dryzek, 2022). Among the various approaches aimed at mitigating and adapting to both anticipated and ongoing changes, education has long been proposed as a seemingly reliable strategy (e.g., Wamsler, 2020). Education on climate change and sustainability issues is often characterised by its interdisciplinary and problem-based nature (McCright et al., 2013) to emphasise the development of practicable skills to tackle global problems. Various approaches can be taken in this endeavour. Climate science education focuses on teaching the scientific basis of the Earth's climate system and the factors affecting it, focusing on atmospheric, oceanic and terrestrial interactions (e.g., Monroe et al., 2019). It is a subset of geoscience education, which covers the Earth's physical systems beyond climate. On the other hand, climate science education is also a subset of climate education, which involves a broad understanding of the climate system, human impacts, and policy responses, thus addressing also climate change impacts, mitigation, and adaptation. Education with such importance yet with such demanding dispositions has been the subject of extensive research and development, encompassing pedagogical methodologies (Perkins et al., 2018), educational outcomes (Kubisch et al., 2022), global implementation (Molthan-Hill et al., 2019) and professional practices (Salovaara and Soini, 2021). Similarly to sustainability, geoscience education as well is thought to require proper contextualisation – of being engaged with relevant locations (King, 2008). To continue, organising geoscience education as situated learning would also suggest that such elements as the learning community and development of professional identity are to be given more attention (Donaldson et al., 2020) and that feelings coming from the exposure to various contexts, cultures and communities ought to be better managed in geoscience education (Hall et al., 2022; Todd et al., 2023). More generally, according to Delors (1996), education of people to manage in the rapid societal changes, the four pillars of learning should be considered: first, learning to know; second, learning to do; third, learning to live together; and fourth, learning to be. The third pillar, inherently connected to sense of belonging and involving the creation of a new spirit based on understanding and recognising others' history, traditions, and spiritual values, is highlighted as vitally important. However, the research on the impact and conditions leading to better communication of geoscience in climate education (e.g., King, 2008) seems to seldomly address a sense of belonging, which centres many of the aforementioned topics.

In higher education, a sense of belonging among students is widely acknowledged for its influence on academic performance and overall success within the university environment. Students with a high sense of belonging tend to have high motivation and enjoyment in their studies (Pedler et al., 2022), self-worth (Pittman and Richmond, 2007) and high academic achievement (Edwards et al., 2022, Pittman and Richmond, 2007), both in online and traditional education set-ups (Edwards et al., 2022; Thomas et al., 2014). Sense of belonging is widely recognised as essential for fostering student engagement in their studies (Thomas, 2012). Previous studies have examined how various domains contribute to students' sense of belonging, including social relationships, academic environments, physical places and overall surroundings, encompassing the entirety of the higher education experience (e.g., Ahn and Davis, 2020). However, it is evident that sense of belonging remains highly personal, with no one-size-fits-all solution (Cohen and Viola, 2022), and ultimately, a student's sense of belonging is grounded in their perception of their connection to a chosen group, place or other entity (Allen et al., 2021; Mahar et al., 2013). Therefore, it is essential to understand the underlying constructs of belonging, independent of specific contexts. This entails understanding the emotional responses and interpretations that lead to both high and low feelings of belonging. By uncovering these fundamental elements, we can gain insights into how to effectively nurture and support students' sense of belonging across diverse educational settings.

This study examines the factors that foster and cultivate a sense of belonging within a particular, interdisciplinary master's programme on environmental changes at high latitudes; operates across multiple universities; and involves students attending courses in different countries and institutions. Studying geosciences in a student group dispersed across various institutes and countries can appear more challenging than a typical graduate student experience consisting mostly of on-site attendance with a relatively stable group of peers and instructors. The master's programme has a unique theme and setup, which impacts the students' sense of belonging. By looking at how their sense of belonging develops and what helps it in this special setting, we learn which conditions are important for belonging. The programme's constantly changing environment – lacking a permanent location or familiar people – makes it even more difficult for students to feel like they fit in. How does a sense of belonging evolve in students who are subject to constantly shifting teaching methods and ever-changing surroundings? In this study, we focus on aspects relevant to sense of belonging, adapting the Allen et al. (2021) framework to emphasise the students' perceptions of their belongingness. Thus, we ask the following questions: what conditions support and foster a sense of belonging in highly dynamic climate education?, and: what attributes do students perceive in their experiences to affect their belongingness?

Sense of belonging is a fundamental human need (Maslow, 1943), and feeling relatedness to other people is crucial for all human motivation (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Sense of belonging can be defined as the emotional attachment that individuals feel towards specific groups, systems or environments (Maestas et al., 2007) and their perception that their personal attributes fit with these entities (Hagerty and Patusky, 1995). Recent re-conceptualisations suggest that belongingness is a dynamic and non-static process that is dependent on situational factors and that the sense of belonging fluctuates over time (e.g. Guyotte et al., 2019). Rather than focusing merely on social connections, belongingness is proposed to be seen as a “situated practice” that is rooted in place (Gravett and Ajjawi, 2022). To continue, state belonging, referring to a sense of belonging that fluctuates over time and is context-dependent, is distinguishable from trait belonging, referring to an individual's inherent tendency to feel belonging irrespective of context (Allen et al., 2021). In geoscience education – also as a practice of communicating geoscience and its ideas further – belongingness has been recognised, predominantly implicitly, as a relevant element. Situated learning has been suggested as a potential key direction of pedagogical development in geoscience education, which has thematic ties to a sense of belonging by its suggested three core components: community of practice – relating to for example social belongingness, authentic context – relating to for example cultural belongingness, and embodiment – relating to for example academic belongingness (Donaldson et al., 2020).

Numerous factors contribute to shaping higher education students' sense of belonging, including peer relationships, engagement and activities with and within the academic community, personal well-being and connection to physical and cultural environments (Ahn and Davis, 2020). Overall, students' sense of belonging in higher education is heavily influenced by the quality of relationships they form with their peers and faculty members (Thomas, 2012). Recent studies have also highlighted the role of place and surroundings as key elements in shaping one's belongingness (Abu et al., 2021; Ahn and Davis, 2020). As higher education becomes increasingly mobile and organised online, belongingness too gets cultivated less in fixed times and spaces (Gravett and Ajjawi, 2022). The rapid shift to online education due to COVID-19, although improved flexibility and accessibility, had a trade-off; challenges arose in maintaining and altogether having a lower sense of belonging among students who were no longer anchored to the physical and temporal boundaries of traditional educational settings (Abu et al., 2021). To continue, geoscience students can also experience a low sense of confidence, which is tied to poorer academic performance (Heron and Williams, 2022) and coincidentally relevant to feelings of belonging. Belongingness, thus, is an outcome of a process of complex experiences in multiple spaces and places (Guyotte et al., 2019, after Braidotti, 2006).

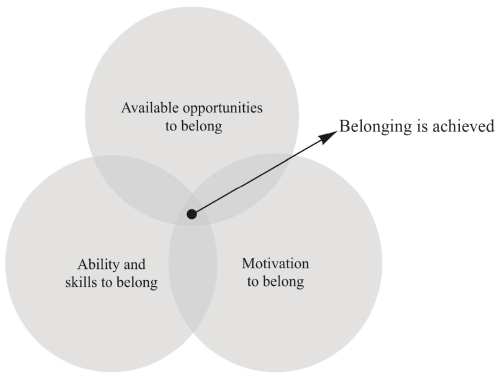

In higher education research, a sense of belonging has been suggested to be composed of feelings associated with various domains, such as the academic environment and community, institutes, people and places, with their cultural significance (Ahn and Davis, 2020; Thomas, 2012). The importance of these elements in contributing to students' sense of belonging varies depending on the individual, thus making belonging a highly personal experience (Cohen and Viola, 2022) contingent upon individuals' perceptions of their belongingness (Allen et al., 2021). To operationalise the theory, we adopt the framing by Allen et al. (2021) on elements that build belonging. Belongingness requires an opportunity to belong, such as an available social, cultural and environmental context to interact with; a motivation to belong to that context; and an ability (necessary resources and skills) to interact with it. However, ultimately, the feeling of belonging is based on the perception of belonging (Allen et al., 2021). In our analysis, we examine how opportunities, motivation and ability to belong serve as conditional factors that facilitate the development of perceived belonging (Fig. 1). Our focus is on understanding the emotional responses and interpretations that contribute to shaping this perception.

3.1 Case programme

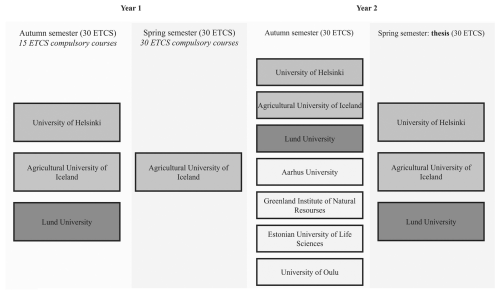

The joint Nordic master programme in Environmental Changes at Higher Latitudes (EnCHiL) is a two-year 120 ECTS Master's programme that is offered by University of Helsinki (UH), Lund University (LU), and the Agricultural University of Iceland (AUI) together with four supporting partner institutes: Aarhus University (Denmark), Greenland Institute for Natural Resources (Greenland), Estonian University of Life Sciences (Estonia) and University of Oulu (Finland). The first cohort of students started their studies in the autumn of 2020. The programme offers education in multidisciplinary environmental/geosciences with a focus on high latitude ecosystems and societies. The aim is to communicate “the underlying processes responsible for environmental changes at higher latitudes (Antarctic, Arctic and sub-Arctic areas)” and to educate to the students with a natural science or engineering background a “deep multidisciplinary knowledge on the past, ongoing and predicted environmental changes at higher latitudes” (The Nordic Master in Environmental Changes at Higher Latitudes, 2024). In addition to the programme's academic goals, it aims to build a strong Nordic contact network for the students.

Students will study in at least two of the degree-awarding institutes (AUI, UH and LU) in which they are expected to spend a minimum of one semester each (Fig. 2). However, all the students spend the spring semester of their first year at AUI where they study compulsory courses together on campus. In addition to the degree-awarding institutes, students can enrol in courses from the partnering institutes listed in the paragraph above.

Figure 2Structure of the EnCHiL programme. Students study the first autumn semester at either the University of Helsinki (UH), Agricultural University of Iceland (AUI) or Lund University (LU). For the first spring semester, all of the students in the cohort study at AUI. During the second autumn semester, the students are free to choose courses from all the degree-awarding and partnering universities and institutions. The second spring semester typically consists of the 30-credit thesis, which the students can submit to any of the degree-awarding universities.

During the first autumn semester of the programme, students start their studies in either AUI, UH or LU. Half of the ECTS credits in the autumn semester are from optional courses, and the other half are from compulsory courses that are offered online for the whole cohort. In the spring, the whole cohort studies in AUI and lives on the campus in Hvanneyri, Iceland. All the spring courses are compulsory. During this semester, the cohort has a field course in Greenland. The second year consists of a 30-ECTS thesis and 30-ECTS optional courses from any of the degree-awarding or partnering institutes. The programme is rather small as the first three cohorts had 5, 10 and 6 students, respectively. Due to the small size of the cohort and the fact that the student body is dispersed among the institutes, only a few students study at the same place at the same time. In the first three cohorts, only 6 out of 21 students were local students from Finland, Iceland and Sweden. Therefore, the majority of the students move from their home country in the beginning of their studies and, due to the mobility scheme, move again to another country at least for one semester. It is to be noted that the main author of this paper is also a graduate of the programme. Thus, this study can be considered to be an insider study (Mercer, 2007) as well, granting the author in question both familiarity to the research case and credibility among the interviewees.

3.2 Interviews and analysis

As we were specifically interested in the empirical reflections and expressions of the students (e.g., Cohen et al. 2018), we adopted a qualitative methodology – typical to education research – also for our exploration. To understand the lived experience of the students, we conducted 15 semi-structured interviews with both current and graduated participants of the programme. The relatively small size of programme cohorts and particular intensive teaching periods can also influence group dynamics and interpersonal relationships, thereby shaping students' experiences of belonging. This led us to mitigate the limitation by interviewing individuals from different cohorts. The interviewees were approached via direct emails (with messages via phone as reminders) introducing the research themes in general and asking for their interest in participating to this study. Along with the initial email, a Participant Information Letter was sent which also acted as a document of implied consent. The letter informed the participants of the study design, data utilisation, and storage, and explained how their answers and anonymity would be handled in the submission. The primary focus of the interviews was to explore the sense of belonging that evolved and was constructed during their time in the programme and to deepen our understanding of the various factors that contribute to shaping the sense of belonging. To continue, we explored the influence of their peer relationships, staff-student interactions, programme curriculum, personal feelings of achievement and the effect their physical surroundings might have had on their overall sense of belonging. We were also interested in whether certain courses or academic experiences held particular significance to their sense of belonging.

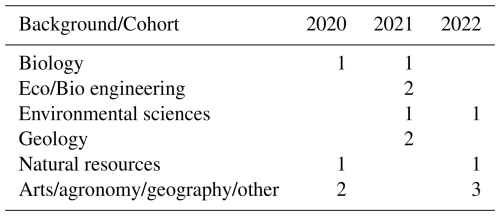

The interviewed 15 students were from the first three cohorts of the programme: four that started their studies in 2020, six in 2021 and five in 2022 (see Table 1). The interviews took place in the summer of 2023. Most interviewees had a bachelor's degree in applied natural or biosciences (e.g. environmental science, geology or biology and related sub-fields), a few had a bachelor's degree in engineering, a few had a bachelor's degree in fields outside natural sciences.

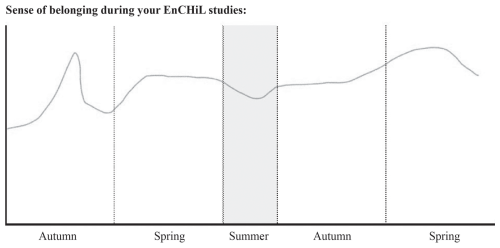

The interviews were conducted as online meetings using the Zoom platform and were between 30 to 75 min in duration. At the start of the interview, we elaborated on the concept of sense of belonging through such descriptions as feelings of attachment to groups, systems or environments, as well as the perception that one's personal characteristics align with those groups, systems or environments. Participants were then provided with a figure schematising a timeline of their studies, on which they were asked to visualise how their sense of belonging changed over time (see Fig. 3). The exercise provided participants with an opportunity to recall and reflect on their experiences during their studies, and the visualisation served as a reference guiding the conversation through periods of varying belonging or shifts in their experiences. Thus, the visualisation served as a concise yet comprehensive overview of the pivotal moments, supporting the verbalisation of their study experience as a whole. The participants had the opportunity to modify and reflect on their visualisations as they continued their musings throughout the interview.

Figure 3Example draft of the drawing exercise that was used to guide the interview. The interviewees were provided with a template representing their timeline in the programme. On the template, they could visualise (e.g. by a line) how their sense of belonging evolved during their studies.

The recorded interviews were later transcribed and subjected to content analysis (Bryman and Burgess, 1994), utilising Atlas.TI for computer-assisted coding. The interviews were initially coded by inductive codes of the interview's key interests, specifically on perceived degrees of belongingness. The initially formed codes were then further grouped into emerging thematic of different types of reappearances (Krippendorff, 2018). A second, confirming round of code grouping was conducted, contrasting the theoretical backgrounds as depicted in Fig. 1 of framing inspired predominantly by Allen et al. (2021). The themes emerged as: ability and skills to belong; motivation to belong; available context to belong to; and emotional responses constructing belonging. Therefore, the results and discussion below are elaborations on these code groups, presented in two main chapters. First, we focus on the theory-backed analysis, describing our empirical insight from the interviewees through the previously theoretically conceptualised sense of belonging. Second, we elaborate on an emerging conceptualisation of sense of belonging, which reveals the construct behind the perceived belongingness rather than describing the conditions of belongingness.

4.1 Necessary conditions to belong

4.1.1 Motivation to belong

Belonging is a basic human need, and motivation is what drives the action to fulfil that need (Ryan and Deci, 2000). In this study, sense of belonging was described to the interviewees as emotional attachment that individuals feel towards specific groups, systems or environments (Maestas et al., 2007). In the academic study setting, the targets of this attachment could be the peer cohort of students, the academic community or institutions representing it, the physical environment, or the scientific content of the study programme, to mention a few. Most students identified the motivation to belong as a necessity. This was specifically true in connection to social interactions within their peer cohort, which is demonstrated by the quotations in this Section. Sense of motivation seemed to coalesce with feelings of responsibility and independence; it was their responsibility to seek opportunities to connect with their peers:

That [activities they did as a group that brought them closer] was all our ideas. There were no teachers telling us to do that; you have to also find it in yourself that you want to do this. So maybe it's hard to organise it also. Interviewee 3

So, it's also up to oneself to kind of make that social network around you, and it's not supposed to be the programme's objective to bring that. Interviewee 6

A few interviewees directly expressed a lack of motivation to belong in their cohort. With these cases, lack of belonging was not explicitly negative, as it was their decision to preclude from such connections:

Sense of belonging to other people [in the cohort] – was not so strong. I don't think it really disturbs my experience overall because I already had a group that I belonged to, so I didn't need another group. It didn't disturb me. Interviewee 11

There are some people with ethics that I will not want to associate myself with. So, I do not feel a sense of belonging to this group. Interviewee 9

In both of the previous cases, interviewees stated to have found other groups of people to interact with, and both attached feelings of belonging to those respective groups. To some extent, the lack of belonging to their peer cohort, even though it was not viewed as negative per se, lowered their sense of attachment to the programme. These results mainly stemmed from the small size of the programme, but were not strongly related to the considerable mobility during the programme, and are thus probably applicable to other small programmes.

4.1.2 Opportunities to belong

Sense of belonging is predicated by concrete opportunities to form relationships with groups, systems or environments (Allen et al., 2021). The accessibility of these opportunities was stated as an important factor governing belongingness. Most opportunities that the interviewees recalled were either intrinsically or instrumentally related to conditions that allowed or restricted social interaction. Social interaction has been consistently found to be the most important aspect affecting student belonging (Thomas, 2012).

The students spent their first spring semester in a small rural town called Hvanneyri in Iceland. For many of the interviewees, their stay in a small seclusive place was seen as a catalyst to heightened sense of belonging to their peer group. The small group, with almost all students accommodated at the campus, made them more dependent on each other and thus created a tighter network of the group:

[It helped with] that sense of belonging because it's a very small community. Everybody, I mean, my dear, everybody knew almost everybody there and the professors. I mean everything was near, like the houses, the campus and everything. So it was like easier to, you know, talk and communicate. So it helped the sense of belonging to not only to the master's [programme] but to the community, to the campus, to the country. Interviewee 7

You also need to be more, not friendly, but patient, with other people. Because if we were just a tiny community and you're always with the same people, you don't want to look for trouble. You just want everyone to be happy. You just see the things in a completely different way. I guess in Helsinki you could meet all the time people, so you don't really care about the personal well-being of everyone because there are so many people […] rather than in Iceland, since we were just a very small community, and there is no one else. You kind of want to know that everyone is feeling great. Interviewee 12

For some, the lack of opportunities to interact with other people outside the programme and the small cohort size were viewed as restrictions to social interaction, as interviewees said:

I was living in the house with just [the programme] students, so you know, taking the courses together and living together really just kind of sucks you into this one place and makes it, yeah, the lack of opportunities to reach out to new people. Interviewee 8

I would have preferred living with other people than who I study with, and I would have preferred also living in a big, or just someplace bigger. But that's just how I get energy from outside my study and the stuff I do outside. Then I tap into university, and I bring in energy from outside, and it was very hard in Iceland to get that of course. Interviewee 6

The importance of having opportunities to spend time together was frequently brought up. Most interviewees preferred informal interaction in regard to building belonging over more formal interaction, such as during classes. For example, interviewee 3 explained that: “only school related [student interaction], feels really professional and distant, and then you don't really get the sense of belonging”. Although courses vitally served as spaces for informal interaction to happen, there was also time for non-curricular activities, particularly during residential and field courses:

Some courses where we are going on trips, so we have to spend time together outside of studying; also that really helps make you feel belonging. Interviewee 3

The strongest sense of belonging arises when you are participating in activities outside of the curriculum, that also involve the local students. So in the case of Helsinki, it is for example going to the sauna, experiencing with everyone. There was a strong sense of belonging. In the case of Iceland, it was the impromptu activities we had. We went cross-logging with the other students. We went to the campfire and things like that. Interviewee 9

[A classmate] and I took methods and measurements and the hydrosphere, geophysics [a course]. So we had a couple of field trips out in the Bay of Helsinki, and so it was very nice to do fieldwork but also to see the city and get to know your teacher and your classmates a lot more closely. For this reason and definitely after that course, I also felt the belongingness and in different ways as well from that experience. […] And you know something like Hyytiälä [a remote forestry research station], that was of course a way to bond with people. We had time to go to the sauna and to swim and to have like lunch time with teachers as well. Interviewee 8

Altogether, engaging in course peer projects was beneficial for belonging, as interviewee 11 explained:

I think in general, group work, trying to figure out things together, sort of makes a group. You know, as we did in Hyytiälä, for example. And so the opposite, I guess you know when you work by yourself, as was my experience mostly in the second year, I was mainly working by myself. Which probably contributed to not feeling as belonging.

Then again, courses with restricted interaction, mostly mentioned as online courses, were consistently thought of as negative for belongingness:

When you don't connect to the people, I think you feel less like you belong. Then you feel like really distant. When I felt the least like belonging [was] probably when we only had online classes, then we were like all really busy just trying to understand this and maybe just the only interaction we were having also was related to school. I really didn't feel good. […] I almost quit the studies, actually. […] I was just also feeling really isolated and yeah, but then I still decided to stay. Interviewee 3

Maybe some of the remote courses that we did kind of in the beginning [decreased the belonging], even though they were interesting […] it feels strange to be working online, like doing a group project with people you've never met and you're just doing it online. And it's very difficult to really kind of connect with the people. Interviewee 10

Many of the answers describing opportunities to belong were strongly connected to very specific features of the programme – online teaching period, field courses, or full semester in a remote location.

4.1.3 Ability to belong

Competency to belong refers to capabilities to connect with other people or environments. Many interviewees brought up how, for example, mental strain decreased their ability to interact with others or to take part in studies, which then affected their sense of belonging. Interviewees explained the linkage between personal well-being and belonging:

If you don't feel good inside, you maybe are not as ready to connect to others. I think, just at least to me, I feel more like I belong to a group if I feel good myself. Interviewee 3

I just struggled with some [psychological challenges] that haven't been diagnosed. […] That's just a personal thing that has been influencing my entire time in this first and second year. Interviewee 6

Related to such strain, some interviewees highlighted how courses with a heavier workload, regardless of if they found the topic interesting, seemed to decrease their sense of belonging. Interviewee 1 said:

So, it was just a lot of workload, so that's the dip [in the belonging in the chart they drew] because it was just like, you had been going on for nine months basically and just no break. I mean I was I was working on Christmas Day even. […] Of course it was a little bit of a dip [in the belonging] because I thought it was difficult to do my master's thesis. You know, it took a lot of me to do it.

Similarly, lacking sufficient readiness (e.g. background information) for a course caused stress and struggles with studies, which again decreased the sense of belonging:

[Low belonging], like when we were doing the statistics and stuff. Then it really like affected my self-esteem. Interviewee 3

Maybe the Greenland course [decreased my sense of belonging] because I don't have a very solid like science background. So, it was like all these measurements and things like that. Interviewee 5

Mental well-being and life satisfaction thus seem to influence the students' sense of belonging, as also noted by Ahn and Davis (2020). Essentially, fostering a sense of belonging in higher education is not isolated from other aspects of life, as, for some interviewees, struggles in personal life decreased their capability to belong – to feel belongingness overall. Studies-related stress can be a significant contributor to students' distress and consequently impair their sense of belonging.

Although diverse learning needs were not specifically in the scope of this study, it is worth mentioning that there are students who experience extra barriers because of neurodiversity or physical disabilities. Importance of adaptive education practices have been highlighted e.g. by Spaeth and Pearson (2023) and Heron et al. (2025).

The results concerning ability to belong are quite general in nature, and thus applicable to different kinds of degree programmes.

4.2 Constructs of belonging

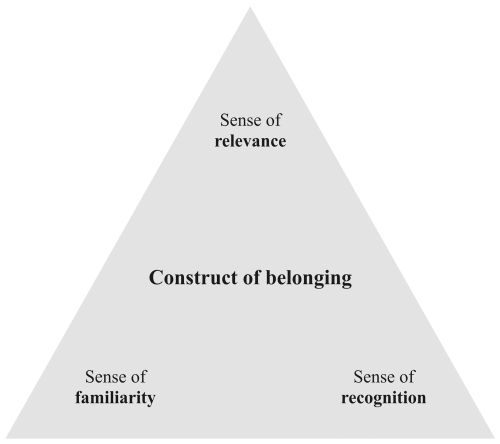

From our analysis of the students' perceived belonging, three dimensions of a sense of belonging construct were identified: sense of familiarity, sense of recognition and sense of relevance. These significantly contributed to the students' feelings of connection, acceptance and engagement with the academic environment. This construct emerged from the interviews as emotional and/or perception dimensions that take part in creating belongingness (Fig. 4). These dimensions were associated with a high sense of belonging in the complex and dynamic educational context that enveloped the students' whole education experience with the EnCHiL programme.

Figure 4The construct of sense of belonging. Based on the content analysis of the interviewees' experiences, three main dimensions were identified by the interviewed students: sense of familiarity, sense of relevance and sense of recognition.

4.2.1 Sense of familiarity

Sense of familiarity was often associated with various elements supporting belonging. Especially in a new environment, encountering something familiar created a sense of comfort and ease that assisted the creation of attachment to new places, countries and institutions. Familiar elements, e.g. in the landscape or in the culture, created a feeling of being “at home”. Interviewee 2 explained how they found the Icelandic landscape familiar: “for me, it was like coming home”. Interviewee 13 explained how, at their apartment in Iceland, they had a mountain view, which reminded them of home: “I belong to the mountains in [my home country]”. To continue, agriculture-related study activities at the campus were familiar to interviewee 2 because of their background, which therefore supported their sense of belonging:

So, I felt like I fit in right away there. […] So I actually think, from the get-go, I really felt like I belonged. But I think it's a combination of the rurality being very familiar to me and the kind of vibe of the campus being familiar for me as well.

Knowing the local language and culture also made it easier to adapt to new settings. Some interviewees had previously spent time in their new place of residence, which they expressed as helpful for feeling belonging:

Well, I mean, for me it was very nice. I already went to Finland that year before Iceland, so I knew the city and I knew, I mean, how everything works. Interviewee 7

I would say that I had a pretty strong sense of belonging just because I knew a little bit of the area and the language and the culture of people. Interviewee 8

Prior knowledge of language and some local customs were important aspects in creating a sense of ease for belongingness, as interviewee 14 elaborated:

So, I think the combination of knowing the physical environment, like knowing the almost bureaucratic processes, but also having a community was kind of crucial to the very stabilised sense of belonging.

Familiarity associated with study topics was also important, as interviewee 5 explained:

The [course about the] geology in Iceland. […] So I mean that was something I was very familiar with, so I've had strong belonging there as well.

Familiarity in course topics indicated competency in the topic in question or a connection to their disciplinary identity. Familiarity with study topics was seen as positive also because of emotional attachment to certain topics.

With my thesis work, I think it makes me more connected, more enthusiastic about it because this is something that I've seen, and I've walked up on this glacier. You know, I've been there and I've seen this my whole life. Interviewee 10

In a study conducted by Kahu et al. (2022), the authors investigated students' sense of belonging during their first year of higher education studies, highlighting the significance of familiarity, particularly during the orientation phase when students acquaint themselves with their studies, surroundings and peers. To continue, according to Antonsich (2010), sense of belonging, marked by a sense of comfort and safety, is highly relevant to one's attachment to a particular place. Given that the programme's students switch their study locations, institutes and social circles at least twice throughout their studies, the importance of familiarity is heightened when they orientate themselves and create a sense of place periodically.

4.2.2 Sense of relevance

Perceiving the programme as academically relevant for the student was beneficial for their sense of belonging. Especially courses that resonated with their future goals, hoped career paths and direction in life in general enhanced the experienced belongingness.

I did some courses here that I was super happy with, and I was like, OK, I'm on the right side of life. This is what I should be doing. […] Yeah, I was working on my master's thesis, and I was also doing research […], and I just really sense that this is what I want to do. I want to be out in the field doing some research, making some papers out of the research that I do, testing things out in nature. Interviewee 1

[When asked which courses increased their sense of belonging] Actually, like the ecosystem ecology [course]. I think that's the one course that stood out for me because it was something a bit new. It was a big course, and I learned so much, and that's the lead into what I'm doing today. Interviewee 5

Coincidentally, studying courses outside their interest areas lowered the sense of belonging for some students. For some, the multidisciplinary nature of the programme was challenging as it led to studying topics outside of their main discipline of interest. For instance, Interviewee 7 described feeling a low sense of belonging during a semester focused on social science subjects, which were perceived as unrelated to their own disciplinary expertise.

For me it was like it was very messy like. I was like not fully understanding […] what was the programme about [when] the second semester was like more like philosophy or environmental values or anthropology or something like that.

Despite integration and a sense of belonging in social relationships, the lack of alignment with their academic interests left them feeling disconnected from the programme.

One interviewee had doubts in their interest in the programme in general. However, they noted that their sense of belonging improved when they enrolled in courses more closely related to their personal interests during the spring semester.

Thinking back, relating to my interest and all, maybe this programme is not the best fit for me because it was maybe more [focused] into another direction [than the interviewee's interests]. But I guess during the spring, I think there I got the belonging, doing two courses that are really fitting my interest. Interviewee 10

4.2.3 Sense of recognition

Recognising oneself as competent and fitting to the study context, and getting external validation for it, was central for supporting belongingness. Several interviewees emphasised the crucial role of supportive teachers in shaping their positive study experience. Specifically, validation and recognition from thesis supervisors was significant for fostering a sense of belonging – potentially because, among all the coursework, thesis work most closely resembles professional research. Interviewee 2 explained that when they were doing their thesis in a research group, being treated as a colleague made them feel like they fit as a “scientist” and into the academic sphere, thus increasing their sense of belonging:

More and more, so kind of in like discussions around like, “have you looked at this paper”, like kind of problem-solving discussions that I really increasingly feel more and more like a scientist, quote, unquote. So that's growing for me [as a domain to feel belonging in].

Interviewee 11 explained how such validation made them feel like they belonged to a research group:

Having had like a successful thesis project has helped me to you know, get a job. So I feel like I belong to that group now. […] You know, doing this stuff well and getting good feedback of course helps in, you know, like establishing yourself in a group context.

As crucial as it was to be recognised for one's competency by others, it was also important to recognise similarities between oneself and others alike – all “fitting in” together:

[Being around] like my kind of people, basically. Yeah, I think that makes you really belong. Like ok, these are the people you want to associate with in the future. Through all of my studies […] I always liked the people I met, there's not often been people that I don't like in this field. […] I mean, like-minded people choose, like, similar paths, basically. Interviewee 1

Evidently, perceived misfitting then led to feelings of loneliness and alienation. Interviewees expressed feelings of detachment from their peers as they perceived themselves to be interested in things different than the majority of their peers:

So, I really felt just on the side and especially because I was doing kind of another thing compared to the others. It was even harder to feel that I belonged there. Interviewee 12

Feeling of being kind of isolated, you know, because I was doing kinds of different things than, you know, you guys and the people around me. I felt like sometimes I was a bit isolated, and [that was] of course affecting my sense of belonging. Interviewee 10

Interviewee 10 explained having missed shared interests with others but managed to find people during some elective courses that better served their interests:

Of course, I missed sometimes like having a chat about what you're doing that is not just me talking about what I'm doing. Actually like somebody giving me feedback or having a discussion on like a deeper level related to the interest. But of course, you know, during the courses I was taking that were really interesting, I had this conversation and I could kind of have this type of, I don't know, feeling I belonged in a group at a certain time, talking about what we are studying and what we are learning.

Recognition, both by oneself and others, plays a central role in fostering feelings of belonging. Being recognised for one's competency by others was also central for the formation of professional identity. For example, Carlone and Johnson (2007) and Hughes et al. (2021) highlight the importance of recognition in a scientist's identity development. Furthermore, Hazari et al. (2020) underscore how sense of belonging contributes to disciplinary identity. Sense of belonging and professional identity development can be thought of as interconnected processes that reinforce each other.

Not being able to share interests or disciplinary identities with other students of the programme was disruptive for some students' sense of belonging. Even though interdisciplinary education is thought of as essential in addressing the complex issues of climate change, it also poses challenges to students with strong disciplinary identities and, consequently, to their sense of belonging. However, some research suggests that exposure to multidisciplinary environments can strengthen disciplinary identities (Geschwind and Melin, 2016).

During master's studies, one's disciplinary identity is still under process. One interviewee explained how learning and engaging with the knowledge community affected their sense of belonging, as it seemingly led to the students to create a shared disciplinary identity:

I think the more you learn about the topic, the more you feel that you belong there. Because the more you know about the topic of your studies, just the more you can connect with other people from your programme. Interviewee 12

4.2.4 Sense of belonging in climate and geoscience education

Effective climate and geoscience communication strategies in education are interconnected with elements that relate to the learner's sense of belonging to their learning community, to the cultures of their study contexts, to the field of experts they are developing to be a part of, and to the interactions with the society around them in their future expert role (Donaldson et al., 2020). In addition, factors that foster a sense of belonging are also recognised as generally effective for climate education (Monroe et al., 2019); paying attention to effective pedagogies and methods of communication ought to heighten the students belongingness and their heightened belongingness ought to strengthen the effect of the education:

“[…] we had a couple of field trips out in the Bay of Helsinki, and so it was very nice to do fieldwork but also to see the city and get to know your teacher and your classmates a lot more closely. For this reason and definitely after that course, I also felt the belongingness and in different ways as well from that experience. Interviewee 8

Familiarity and connection with places and locations are beneficial for belongingness, for example; place attachment can motivate someone to climate action (Devine-Wright, 2013) and is thus a relevant aspect in climate change education. By incorporating local and tangible aspects of climate change and sustainability, educators can foster a deeper connection between students and the subject matter, provide meaningful learning experiences while enhancing their understanding of the topic, and manage a better comprehension of the plurality of perspectives that are attached to geosciences (Hall et al., 2022). Thus, creating a learning environment where students can connect to the subject matter in relevant context – be it socially, culturally, geospatially – appears as a key element for effective climate change education:

[in] Helsinki and Iceland I feel much more like I belong to the whole operation, you know? I feel respected as a contributor, as a collaborator and not just as someone who is only coming to listen and take, but as someone who is contributing. I think this is maybe cultural. […] but then of course, the teachers make a difference, and other people […] made it possible to feel like we belong to this operation – that I felt like I'm welcome there and am accepted. Interviewee 1

While interdisciplinary education is essential for addressing the complexity of climate change (McCright et al., 2013) and geoscience education benefits from happening in relevant locations (King, 2008), high mobility and interdisciplinarity can also pose challenges to students' sense of belonging, learning and professional identity development (Donaldson et al., 2020; Geschwind and Melin, 2016). Support for the students' disciplinary and pre-professional identities is crucial as, for example, directing the students to self-determine the scope of their courses can result in having expertise in the core of geoscience concepts (King, 2008) and through interdisciplinarity of the programme also enhance skills for communication of the science itself – and simultaneously enhance their sense of belonging:

I think as an a graduate from the programme and belonging to that part of the Nordic environmental science academic community – a very small group, but a group who have had very similar experiences – it's been a great way to share knowledge of opportunities and programs and further training and the way that we have kind of connected [on professional social medias] as well to throw that name out there in terms of growing my network in high-latitude environmental science – and connecting to people who are outside of my home country but working in the Nordic area. Interviewee 15

4.3 Limitations and future research

With our study aimed to shed light on students' sense of belonging within a multidisciplinary master's programme, we will address some acknowledged limitations in broader contextualisation of the findings. First, the unique nature of the programme, characterised by its high level of mobility and research orientation, is a potentially limiting factor. The alignment between the programme and career aspirations of the participants could differ for students in other climate science-oriented programmes; most likely making their future prospects in terms of locations and organisations more varied. Second, the language proficiency of interviewees may have caused minor limitations in their ability to articulate their experiences more effectively during interviews. Despite these limitations, our study contributes valuable insights into the multifaceted nature of sense of belonging within the context of higher education, particularly in multidisciplinary programmes focused on climate change and sustainability. With future research, we would address the mentioned limitations in the breadth and width of sample groups, further mitigating any factors influencing the theories and methods employed here. To continue, future research endeavours on students' sense of belonging, its effect on transformative learning and epistemic identity development and, foremost, the effect on the potential of effective impactful geoscience communication and education are surely due.

The purpose of this study was to explore students' sense of belonging and the conditions for it in a multidisciplinary master's programme. Our interest in the programme stemmed from its high level of mobility, which poses a challenge to students in forming a sense of belonging compared to a typical educational setting. The chosen theoretical approach and the formulated framings for the interviews and further content analysis seemed to function well for the purpose and led to relevant and original insights. The semi-structured interviews among the purposefully sampled group of 15 students showcased the theory-suggested conditions for sense of belonging, namely motivation, opportunities and the ability to belong, and their empirical appearance among the students. Furthermore, an additional grounded construct of the sense of belonging emerged from the analysis of this specific study. This construct is built on students' sense of familiarity, recognition, and relevance. We believe these feelings can clarify the often unclear role of sense of belonging as an important part of learning. This is crucial for effectively teaching geoscience, considering the discipline's many applicable locations and varied contexts. Considering this sense of belonging construct, we thus suggest that educational planning, curriculum design and professional development in climate change and sustainability-related education at large ought to consider the sense of familiarity, recognition and relevance as utilisable bridges to strengthen the learners' belonging in a given programme, or context, even if in constant flux.

No custom code was used to generate the results in this paper.

Due to the nature of the research, supporting data are not available. The participants of this study, as private individuals, were not asked to share the data related to their participation publicly.

Conceptualisation and methodology by SK, SJJ, VVM, and LKA; investigation by SK and SJ; analysis by SK, SJJ, VVM, SJ, and LKA; original draft preparation by SK; writing by SK and SJJ; reviewing by SK, SJJ, VVM, LKA, SJ, KSA, and RL; and revision editing by SJJ, SK and LKA.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

This study was performed under ethical guidelines from the University of Helsinki. However, explicit review by ethical research board for this study was not mandatory.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

One of the authors, Prof. Katariina Salmela-Aro passed during the review process of this paper. With grief, the other authors wish to express their deep gratitude for her crucial role in the conceptualisation of this study. The authors wish to thank the interview participants who were willing and open to share their lived experiences for the purposes of this research. We also thank the board of the Nordic Master in Environmental Changes at Higher Latitudes, and especially the director of the programme, Prof. Bjarni D. Sigurdsson from the Agricultural University of Iceland for giving insight into the programme and access to programme documents, and for enabling us to reach the past and present students of the programme. In addition, we want to acknowledge the editor and editorial office of this journal and the anonymous reviewers who gave their time and attention to improve the quality of our submission.

This research received funding from The Research Council of Finland, under grant: 340791 (Project: “Learning of the competencies of effective climate change mitigation and adaptation in the education system”) and from the Nordplus programme of the Nordic Council of Ministers, under grant: NPHE-2023/10209 (Network: “ABS – Atmosphere-Biosphere Studies”, Project: “We belong – contributing to a sustainable development of international education”). Open Access funded by Helsinki University Library.

This paper was edited by Stephanie Zihms and reviewed by Fabio Crameri and Maurits Ertsen.

Abu, L., Chipfuwamiti, C., Costea, A.-M., Kelly, A. F., Major, K., and Mulrooney, H. M.: Staff and student perspectives of online teaching and learning; implications for belonging and engagement at university – a qualitative exploration, Compass J. Learn. Teach., 14, https://doi.org/10.21100/compass.v14i3.1219, 2021.

Ahn, M. Y. and Davis, H. H.: Four domains of students' sense of belonging to university, Stud. High. Educ., 45, https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1564902, 2020.

Allen, K.-A., Kern, M. L., Rozek, C. S., McInerney, D. M., and Slavich, G. M.: Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research, Aust. J. Psychol., 73, https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1883409, 2021.

Antonsich, M.: Searching for belonging–An analytical framework, Geogr. Compass, 4, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00317.x, 2010.

Braidotti, R.: TRANSPOSITIONS: ON NOMADIC ETHICS, Malden, MA, Polity Press, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL22720801M/TRANSPOSITIONS_ON_NOMADIC_ETHICS (last access: 11 December 2025), 2006.

Bryman, A. and Burgess, R. G.: Analyzing Qualitative Data, 11, Routledge, London, UK, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL38743815M/Analyzing_Qualitative_Data (last access: 11 December 2025), 1994.

Carlone, H. B. and Johnson, A.: Understanding the science experiences of successful women of color: Science identity as an analytic lens, J. Res. Sci. Teach., 44, 1187–1218, https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20237, 2007.

Cohen, E. and Viola, J.: The role of pedagogy and the curriculum in university students' sense of belonging, J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract., 19, 6, https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.T2024121200020601774838377 (last access: 11 December 2025), 2022.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K.: Research Methods in Education, 8th edn., Routledge, London, UK, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203224342, 2018.

Delors J.: Learning: the treasure within; report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the Twenty-first Century (highlights), UNESCO, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000109590 (last access: 11 December 2025), 1996.

Devine-Wright, P.: Think global, act local? The relevance of place attachments and place identities in a climate-changed world, Glob. Environ. Change, 23, 61–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.08.003, 2013.

Donaldson, T., Fore, G. A., Filippelli, G. M., and Hess, J. L.: A systematic review of the literature on situated learning in the geosciences: Beyond the classroom, Int. J. Sci. Educ., 42, 722–743, https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2020.1727060, 2020.

Dryzek, J. S.: The Politics of the Earth: Environmental discourses, Oxford university press, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL28494236M/Politics_of_the_Earth (last access: 11 December 2025), 2022

Edwards, J. D., Barthelemy, R. S., and Frey, R. F.: Relationship between course-level social belonging (sense of belonging and belonging uncertainty) and academic performance in general chemistry 1, J. Chem. Educ., 99, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00405, 2022.

Geschwind, L. and Melin, G.: Stronger disciplinary identities in multidisciplinary research schools, Stud. Contin. Educ., 38, 16–28, https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2014.1000848, 2016.

Gravett, K. and Ajjawi, R.: Belonging as situated practice, Stud. High. Educ., 47, https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1894118, 2022.

Guyotte, K. W., Flint, M. A., and Latopolski, K. S.: Cartographies of belonging: mapping nomadic narratives of first-year students, Crit. Stud. Educ., 62, 543–558, https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1657160, 2019.

Hagerty, B. M. and Patusky, K.: Developing a Measure of Sense of Belonging, Nurs. Res., 44, https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1097/00006199-199501000-00003 (last access: 11 December 2025), 1995.

Hall, C. A., Illingworth, S., Mohadjer, S., Roxy, M. K., Poku, C., Otu-Larbi, F., Reano, D., Freilich, M., Veisaga, M.-L., Valencia, M., and Morales, J.: GC Insights: Diversifying the geosciences in higher education: a manifesto for change, Geosci. Commun., 5, 275–280, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-5-275-2022, 2022.

Hazari, Z., Chari, D., Potvin, G., and Brewe, E.: The context dependence of physics identity: Examining the role of performance/competence, recognition, interest, and sense of belonging for lower and upper female physics undergraduates, J. Res. Sci. Teach., 57, 1583–1607, https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21644, 2020.

Heron, P. J. and Williams, J. A.: Building confidence in STEM students through breaking (unseen) barriers, Geosci. Commun., 5, 355–361, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-5-355-2022, 2022.

Heron, P. J., Crameri, F., Canaletti, E. F., Harrison, D., Hashemi, S., Leigh, P., Narayan, S., Osowski, K., Rantanen, R., and Williams, J. A.: Art, music, and play as a teaching aid: applying creative uses of Universal Design for Learning in a prison science class, Front. Educ., 10, 1524007, https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1524007, 2025.

Hughes, R., Schellinger, J., and Roberts, K.: The role of recognition in disciplinary identity for girls, J. Res. Sci. Teach., 58, 420–455, https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21665, 2021.

Kahu, E. R., Ashley, N., and Picton, C.: Exploring the complexity of first-year student belonging in higher education: Familiarity, interpersonal, and academic belonging, Stud. Success, 13, 10–20, https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.2264, 2022.

King, C.: Geoscience education: an overview, Stud. Sci. Educ., 44, 187–222, https://doi.org/10.1080/03057260802264289, 2008.

Krippendorff, K.: Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, Sage Publications, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781, 2018.

Kubisch, S., Krimm, H., Liebhaber, N., Oberauer, K., Deisenrieder, V., Parth, S., Frick, M., Stötter, J., and Keller, L.: Rethinking quality science education for climate action: Transdisciplinary education for transformative learning and engagement, Frontiers in Education, 7, 838135, https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.838135, 2022.

Maestas, R., Vaquera, G. S., and Zehr, L. M.: Factors impacting sense of belonging at a Hispanic-Serving Institution, J. Hisp. High. Educ., 6, https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192707302801, 2007.

Mahar, A. L., Cobigo, V., and Stuart, H.: Conceptualizing belonging, Disabil. Rehabil., 35, https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.717584, 2013.

Maslow, A. H.: A theory of human motivation, Psychol. Rev., 50, 430–437, 1943.

McCright, A. M., O'shea, B. W., Sweeder, R. D., Urquhart, G. R., and Zeleke, A.: Promoting interdisciplinarity through climate change education, Nat. Clim. Change, 3, 713–716, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1844, 2013.

Mercer, J.: The challenges of insider research in educational institutions: Wielding a double-edged sword and resolving delicate dilemmas, Oxf. Rev. Educ., 33, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980601094651, 2007.

Molthan-Hill, P., Worsfold, N., Nagy, G. J., Leal Filho, W., and Mifsud, M.: Climate change education for universities: A conceptual framework from an international study, J. Clean. Prod., 226, 1092–1101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.053, 2019.

Monroe, M. C., Plate, R. R., Oxarart, A., Bowers, A., and Chaves, W. A.: Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the research, Environ. Educ. Res., 25, 791–812, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842, 2019.

Pedler, M. L., Willis, R., and Nieuwoudt, J. E.: A sense of belonging at university: Student retention, motivation and enjoyment, J. Furth. High. Educ., 46, https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1955844, 2022.

Perkins, K. M., Munguia, N., Moure-Eraso, R., Delakowitz, B., Giannetti, B. F., Liu, G., Nurunnabi, M., Will, M., and Velazquez, L.: International perspectives on the pedagogy of climate change, J. Clean. Prod., 200, 1043–1052, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.296, 2018.

Pittman, L. D. and Richmond, A.: Academic and psychological functioning in late adolescence: The importance of school belonging, J. Exp. Educ., 75, https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.4.270-292, 2007.

Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L.: Self-Determination Theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being, Am. Psychol., https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68, 2000.

Salovaara, J. J. and Soini, K.: Educated professionals of sustainability and the dimensions of practices, Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 22, 69–87, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-09-2020-0327, 2021.

Spaeth, E. and Pearson, A.: A reflective analysis on neurodiversity and student wellbeing: conceptualising practical strategies for inclusive practice, J. Perspect. Appl. Acad. Pract., 11, 109–120, https://doi.org/10.56433/jpaap.v11i2.517, 2023.

The Nordic Master in Environmental Changes at Higher Latitudes (EnCHiL): About Enchil, https://enchil.net/about-enchil/, last access: 2 May 2024.

Thomas, L.: Building student engagement and belonging in Higher Education at a time of change, Higher Education Academy, York, UK, https://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/427066 (last access: 11 December 2025), 2012.

Thomas, L., Herbert, J., and Teras, M.: A sense of belonging to enhance participation, success and retention in online programs, Int. J. First Year High. Educ., 5, https://doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v5i2.233, 2014.

Todd, W. F., Towne, C. E., and Clarke, J. B.: Importance of centering traditional knowledge and Indigenous culture in geoscience education, J. Geosci. Educ., 71, 403–414, https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2023.2172976, 2023.

Wamsler, C.: Education for sustainability: Fostering a more conscious society and transformation towards sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 21, 112–130, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-04-2019-0152, 2020.