the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Assessment of a youth climate empowerment program: Climate READY

Anne Henderson

Ray Coleman

Christopher Hill

Bradford T. Davey

This article presents an in-depth assessment of a youth, climate empowerment program, called Climate READY – Climate Resilience Education and Action for Dedicated Youth. It was developed by the Florida Atlantic University Pine Jog Environmental Education Center (FAU Pine Jog) and funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Environmental Literacy Program. The program built climate literacy and community resilience through a three-semester dual-enrollment program (financed by grant no. NOAA-SEC-OED-2020-2006190). Most student participants (∼80 %) were from Title 1 high schools in low socio-economic communities vulnerable to extreme weather and environmental hazards in Palm Beach County, Florida (see definition in Appendix A). The main objectives of this program were to

-

increase knowledge of south Florida's changing climate systems;

-

teach and promote environmentally responsible behavior, which results in the stewardship of healthy ecosystems and a reduction in carbon consumption to mitigate future environmental risks; and

-

empower students to act as agents of change within the community by teaching community members about local climate impacts and resilience strategies for extreme weather events.

Important characteristics of the program included the following:

-

Students ages 15 to 17 years old registered for the Climate READY Ambassador Institute (summer semester 1) built climate knowledge, explored NOAA Science on a Sphere technology, engaged with scientists and resilience experts, developed communication and advocacy skills, and learned about local resilience solutions. At the end of the course, these students were given completion certificates and the title Climate READY Ambassadors (CRAs).

-

An after-school mentorship (fall semester 2) component paired new Climate READY Ambassadors with fourth- and fifth-grade after-school students ages 9 to 11 years old to build community resilience awareness through four structured lessons and the creation of storybooks. Lastly, community outreach (spring semester 3) provided ways for Climate READY Ambassadors to share local resilience strategies at public events and promoted civic engagement in climate solutions.

Data were collected from all students in the form of pre- and post-assessment questionnaires during the 2022–2023 academic year. Summative statistics were analyzed for climate science knowledge, self-identity, self-efficacy, and sense of place. Climate READY Ambassadors felt more prepared, confident, and able to communicate within their communities about climate change, and many demonstrated a significantly better understanding of climate science concepts. After-school students showed a better understanding of climate change and were able to identify ways to help reduce the effects of climate change. Both groups of students benefitted from the Climate READY Ambassador mentorship, demonstrating learning by doing and learning by storytelling.

- Article

(10154 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) provides evidence that climate change is certain to unleash serious impacts globally, including an increase in the exposure of coastal areas to natural disasters (IPCC, 2023). A community's vulnerability to natural disasters is a combination of the exposure to the risk that the community faces coupled with the community's available social, economic, political, and institutional resources that allow them to adapt (IPCC, 2023; Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact, 2022). To prepare for a future of increasing hazards, communities will need an informed public that is willing to act on decisions at a personal and civic level. How people prepare for, respond to, and cope with natural disasters is linked to community resilience, – in other words, how well a community can bounce back when a natural disaster occurs (Ronan and Johnston, 2005). This kind of preparedness requires a minimal level of environmental literacy, by which we mean the possession of knowledge and understanding of a wide range of environmental concepts, problems, skills, and abilities. A more environmentally literate public makes more informed decisions and is more involved on a community level, which contributes to community resilience. The complexity of climate change science often makes it difficult for a less climate-literate general public to gain a thorough understanding, severely impeding their ability to make informed decisions for themselves, their families, and their communities.

A solution to this lack of understanding is education, particularly in schools. A survey in 2012 by Florida Atlantic University (FAU) revealed that over 67 % of respondents in south Florida felt that the causes, consequences, and solutions to climate change should be taught in K-12 (youth ages 5 to 18 years old) classrooms (Lambert et al., 2012). According to a series of surveys conducted by Florida Atlantic University's Center for Environmental Studies (CES), the percentage of Floridians that believe climate change is occurring and that it is caused by human activities has increased from 56 % to 64 % over a 5-year period (Florida Climate Resilience Survey, 2019, 2024). The latest CES survey also indicated that 69 % of Floridians support the statement that ”Florida schools should teach the causes, consequences, and solutions to climate change in our K-12 classrooms” and that ”more than two-thirds of respondents have supported climate education in schools in 10 of the 11 surveys since October 2019” (The Invading Sea Florida Climate Survey, 2024). This data indicate an improvement in public perception of climate change education in Florida, yet it and the science of evolution remain a topic of debate among Florida legislature (Haught and Austin, 2018). However, the educational community, particularly in the state of Florida in the United States (US), has yet to embrace climate change as a subject that is routinely taught. One reason may be that many teachers are not comfortable with the subject and lack the confidence to be able to teach it to their students (Lambert et al., 2012). Another survey suggests that negative emotions surrounding the topic are increasing climate anxiety among teachers, which could help explain hesitancy in climate science curriculum delivery to students (Clayton et al., 2023). When compared to other states in the US, the topic of climate change is less prevalent in Florida's classrooms, but the state standards are not currently devoid of statements about climate education (National Center for Science Education and Texas Freedom Network Education Fund, 2020; CPALMS, 2024). Oftentimes, a standard will cover relevant lessons without specifically mentioning climate change, while at other times, the issue is combined with other subjects (Sabella, 2019). Without some kind of professional development, teacher support, or ability to devote time to subjects such as climate change and environmental sustainability, teachers are unlikely to approach these topics with their students. As a result, climate change has yet to make it into mainstream education in the Florida classroom.

1.1 Climate change education and youth empowerment in the US

Many resources and effective strategies that teach climate change science and to some extent climate advocacy to youth-based audiences and beyond are available to teachers in the United States (Busch, 2016; Drewes et al., 2018; Filho and Hemstock, 2019; Ledley et al., 2014; Monroe et al., 2019; Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020; Zabel et al., 2017). In addition, youth voices and their call for climate action have been of particular note to improve accessibility to factual information that increases climate change knowledge and, perhaps more importantly, provide avenues to actively and effectively participate in real solutions for society, including youth involvement in public discussions and planning processes (Busch et al., 2019; Kretser and Chandler, 2020). Organizations such as The Climate Reality Project based in Washington, DC (2006); The Wild Center Youth Climate Program in Tupper Lake, New York (2008); The Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network (CLEAN) based in Boulder, Colorado (2010); and FXB Climate Advocates based in New York, NY (FXB Climate Advocates, 2019) have all made considerable efforts to improve climate change education, information, and youth involvement within the United States. Of particular note, CLEAN developed a “rigorous iterative peer-review process” to curate digital content such as videos and visualizations that address climate and energy literacy principals (Gold et al., 2012). Using geospatial visual tools to display complex data such as climate, weather, and currents has been an important aspect of teaching climate change (Hestness et al., 2014; Niepold et al., 2008; Wolf-Jacobs et al., 2024).

Locally in Florida, The Climate Leadership Engagement Opportunities (CLEO) Institute based in Miami (2010), led by former science teacher and educational administrator Caroline Lewis, provides a curriculum, training, webinars, and more to foster climate literacy and support action-based resources. In addition, the authors of this paper from the FAU Pine Jog Environmental Educational Center (FAU Pine Jog) have experience in teaching climate change and supporting teachers and youth action in Florida prior to this research (Wellman and Henderson, 2022). However, few Florida teachers will address the topic of climate change without administrative support or time to prepare for those lessons unless the topic is clearly aligned with state standards.

Content standards in the United States (US) are determined by individual states. As of 2020, Florida uses Benchmarks for Excellent Student Thinking (B.E.S.T) for Math and English Language Arts (ELA), which has had mixed reviews (Berner and Steiner, 2020; Friedberg et al., 2020; Wurman et al., 2020). In 2008, Florida adopted The Next Generation Sunshine State Standards for Science (NGSSS) (Florida Department of Education, 2008). This is not to be confused with the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) that was adopted by at least 20 US states or used as a framework by at least another 20 US states (Bybee, 2014; Next Generation Science Standards For States, 2013; OpenSciEd, 2024). All of Florida's standards can be reviewed using their portal provided by Florida State University (CPALMS, 2024). These standards are used to guide teachers through lessons and provide a source of information for Florida's K-12 statewide assessment program, which measures student success (Florida Department of Education, 2024). Therefore, teachers are expected to teach lessons with specific learning goals that target a state standard. If activities and materials do not align with a standard, then teachers are not going to be encouraged to use them. The curriculum for climate change education in Florida is written with target standards from institutions such as The CLEO Institute and FAU Pine Jog, so there seems to be more to the story.

Interestingly, a study conducted in North Carolina indicated that teachers simply did not have the time to participate in climate change professional development (Ennes et al., 2021). As a public-school teacher in Florida from 2014 to 2022, author Rachel Wellman can relate.

Teachers are given many tasks throughout each school day and every minute counts. We are not paid for overtime, so any prep, grading, lesson researching, and even communications with students and their parents are often outside of a contracted paid time. Workdays can be 12 to 16 h long for duties to be performed at high quality. Designated professional development days are often pre-planned by school districts or individual school administrators. It is difficult to balance work and home life during a school year and most teachers need their time off to recharge, so the last thing they want to do is extra professional development.

Teacher burnout is a well-documented issue in the profession (Chang, 2009; Ghanizadeh and Jahedizadeh, 2015), and stress and anxiety from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic only amplified the problem from 2020 to 2022 (Pressley et al., 2021). Therefore, teachers rarely seek out extra professional development beyond the requirements given by school districts and administrators in Florida.

Financial incentives can also be a factor in gaining teacher participation. Investigative reporting on the issue suggested that many curriculum materials available on the topic of climate change in the US are generated by the energy industry. Wealthy companies will often produce and distribute curriculum materials and sponsor groups/teachers to use their materials while teaching subjects such as climate change. These messages can confuse the cause and effects of the phenomena, increasing uncertainty, confusion, and distrust about climate science (Worth, 2021).

The good news is that we still have hope for our youth and for the future of climate change education in the US. In addition to programs already mentioned here, some success in teacher professional development has been noted at FAU Pine Jog through collaborations with Earth Force, where teachers were given stipends to develop, implement, and document lesson plans that focused on student action civics related to climate change, and a teacher collaborative network was formed (Environmental Action Civics, 2024; Wellman and Henderson, 2022). Students within these classrooms are using place-based and/or project-based learning to help them be part of the solution (Sobel, 2006). More success seems to come from providing services that support the students directly. Many students are motivated, dedicated, reaching out for resources and information, and developing their own programs (Youth Climate Summits) through the support of science and education centers (Han and Ahn, 2020; Kretser and Griffin, 2020; McDonnell et al., 2011). Others are engaging in local and international meetings, designing solutions, conducting experiments, and completing petitions for local governments to take action (Climate Change Education.Org, 2024; Parker, 2020; The Sink or Swim Project, 2016). This type of learning through experience creates engaged citizens as students see their visions through successful outcomes (Burke et al., 2020). As an added result, intergenerational learning seems to be occurring where actions and attitudes coming from our students and children can and have influenced climate change perceptions among their parents, teachers, and other adults (Lawson et al. 2019). Empowering students, giving them hope for positive change in light of an otherwise dreary outlook of climate change, and allowing them to investigate and provide service through action in the community will foster a stronger community for a better tomorrow (Li and Monroe, 2019). The best thing we can do as mentors, parents, and teachers is support them throughout the process.

1.2 Program overview and theoretical framework

This 3-year program, entitled Climate Resilience Education and Action for Dedicated Youth program (Climate READY program), was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Environmental Literacy Program grant (grant no. NOAA-SEC-OED-2020-2006190). Using the Design and Development research model (Earle et al., 2013), the program provided the opportunity to use an original curriculum developed by FAU Pine Jog and NOAA assets to strengthen community resilience and adaptive capacity of participants. Specifically, these students were in grades 4 through 12 (youth ages 9 to 17 years old), with recruitment priority given to underrepresented schools and residents of the larger community in Palm Beach County, Florida. Participants learned the scientific principles behind the global and local changes in climate and studied the relationships and power dynamics of nature, self, and community, which enabled them to become agents in protecting resources and building greater resilience against extreme weather events. Participants also studied the Regional Climate Action Plan (RCAP), which is a guiding tool for coordinated climate action in southeast Florida to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and build climate resilience (Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact, 2022). The RCAP provided a set of over 100 recommendations and guidelines for implementation and shared best practices for local entities to align with the regional agenda. The Climate READY program was delivered over 3 years as described in our methods. The three main components were the (1) Climate READY Ambassador Institute, (2) Climate READY After-school Program, and (3) Climate READY Community Outreach.

The design of this program was informed by the NOAA Community Resilience Education Theory of Change theoretical framework, which outlines the goals of community resilience education (Bey et al., 2020) as a means to develop environmental literacy to understand threats and implement solutions that build resilience to extreme weather, climate change, and other environmental hazards, including the knowledge, skills, and confidence to

-

reason about the ways that human and natural systems interact globally and locally, including the acknowledgement of disproportionately distributed vulnerabilities;

-

participate in civic processes; and

-

incorporate scientific information, cultural knowledge, and diverse community values when taking action to anticipate, prepare for, and respond to hazards.

1.3 Geographic location and hazard identification

The implementation of all three components of the Climate READY program occurred in six specific regions within Palm Beach County in the southeastern region of Florida. These included Boca Raton, Boynton Beach/Delray Beach, Lake Worth Beach, Riviera Beach, West Palm Beach, and the Glades areas (Pahokee/Belle Glade) located near the Everglades Agricultural Area (Fig. 1). For south Florida, the dense population, low-lying coasts, porous geology, and distinctive hydrology characterize it as one of the world's most vulnerable areas to the impacts of climate change. In fact, south Florida could be the next environmental “ground zero” (University of Miami Frost Institute for Data Science and Computing, 2015; see definition in Appendix A). Sea level rise, threatening water and air quality, saltwater intrusion, and destruction of the Everglades are some of Florida's most pressing challenges. South Florida is exposed to nearly all of the nationally identified risks of climate change, including urban infrastructure and health risks, increasing flood risks in coastal and low-lying regions, transformation of natural ecosystems, economic and health risks for agricultural communities, increased prevalence of disease-carrying insects, increased frequency of hot-weather temperatures, hurricane and storm intensification, risks associated with sea level rise and storm surge, increase in invasive species, and threatened freshwater quantity and quality (U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2016). The short-term projections for sea level rise in southeastern Florida are between 6 and 10 in. (15 and 25 cm) by 2030 and 14 to 26 in. (35 to 66 cm) by 2060. In the longer term, sea level rise is projected to be between 31 and 61 in. (78 and 155 cm) by 2100. This rise is due to increasing ocean volume caused by the thermal expansion of water, groundwater losses, glacier mass loss, and discharge from land-based ice sheets (Heimlich et al., 2009). According to a study by Hauer et al. (2016), a sea level rise at this level would affect between 24 000 and 57 000 people in Palm Beach County alone. Additionally, according to the NOAA Theory of Change, “societal processes have created unequal exposures to environmental threats and access to solutions within a community” (Bey et al., 2020). This is certainly true in Palm Beach County. The Social Equity Key to Southeast Florida RCAP 2.0 fact sheet highlights the growing concern for low-income areas and communities of color (Center for American Progress et al., 2018):

Communities of color and low-income areas are disproportionately exposed to heat, flooding, and pollution risks – meaning extreme weather events often hit them hardest. In a region where city streets flood even on sunny days, and in the wake of the record-breaking 2017 hurricane season, local leaders recognize that they have little time to waste (p. 1).

Climate change threats exacerbate and multiply historic inequities that exist in low-income areas and communities of color…. Many communities of color were purposefully sidelined by 20th-century development decisions resulting in economic and racial segregation, making it particularly difficult for communities without targeted policies and resources to build local economies that are just and resilient to climate change (p. 1).

Low-income areas and communities of color are particularly vulnerable to the effects of extreme weather because they are often located in or near flood-prone areas, heat islands – urban neighborhoods where concrete and asphalt surfaces absorb and radiate heat, producing temperatures that are warmer than average – or toxic waste sites. They are also often overburdened by disproportionately high air and water pollution (p. 1).

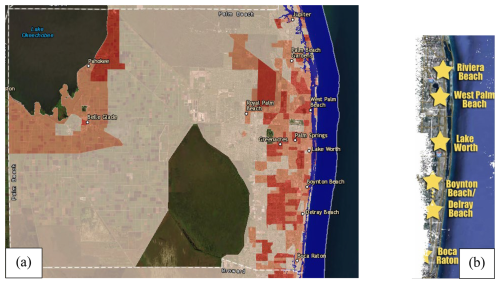

Figure 1Palm Beach County vulnerability (NOAA's Office for Coastal Management Sea Level Rise Viewer, https://coast.noaa.gov/digitalcoast/tools/slr.html, last access: September 2023). Zones in red represent high vulnerability, personal disruption, and risk, and pink zones demonstrate medium indicators of risk and social vulnerability (a). Map of coastal communities targeted in the Climate READY program that was used as part of FAU Pine Jog presentation template (b).

In looking at the Glades areas of Pahokee and Belle Glade (Fig. 1) as an example, the demographics reveal some of the most challenging conditions that exist in the state of Florida and most likely the nation, compounding the struggle that educators have in making climate education a priority. For example, the following is true for this area:

-

72 % of people live in single-parent or nontraditional households;

-

74 % of people live in households earning less than USD 29 999 a year;

-

93 % of students receive free or reduced lunch;

-

35 % of people live in households earning less than USD 11 999 a year;

-

crime rates place Belle Glade as safer than only 4 % of US cities and Pahokee safer than only 10 % (Belle Grade, 2022; Pahokee FL Crime Rates, 2022; Badcock, 2018);

-

78 % are Black/African American, 5 % are Hispanic, 4 % are multiracial, 12 % are undeclared, 1 % are White.

Other targeted areas in Florida are equally dangerous and highly affected by poverty. In 2018, two of the target cities, Riviera Beach and Lake Worth Beach, ranked 30th and 31st as the most dangerous cities in the United States (Todaro, 2018). Complicating Florida's climate and human challenges is Florida's growing population. The US census data indicate that approximately 960 people relocate to Florida each day. Given Florida's population growth, which is expected to grow to 33.7 million by 2070, and development trends, new community-based approaches to conservation education and restoration are imperative (Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services et al., 2017). Florida is now the third-most-populous state, and by 2030, 5 million more residents will call Florida home, and 1.7 million more jobs will be needed (Florida Chamber Foundation, 2017). In 2018, Florida's population of people of color under the age of 70 became a majority at 53.5 % of the population (Taylor, 2019).

1.4 Program objectives and hypothesis

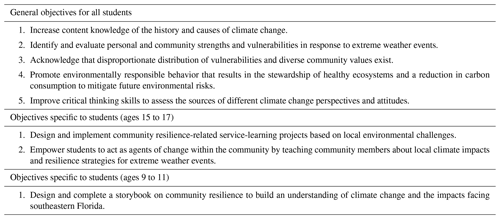

The main goal of the Climate READY program was to increase the environmental literacy of 4th- through 12th-grade students in Palm Beach County, Florida, and the general community that they live in so that they can become more resilient to extreme weather and/or other environmental hazards, thus empowering them to become involved in achieving that resilience. Therefore, our research hypothesis for the program was that participants in Climate READY will better understand their community strengths and vulnerabilities to a changing climate and that they will feel empowered to participate on both a personal and a civic level to take action, minimize risks, adapt, and weigh the potential impacts of their decisions. This goal and hypothesis are in keeping with the NOAA Resilience Theory of Change theoretical framework, which theorizes that “environmental literacy, along with community health, civic engagement, social cohesion, and equity, enhance resilience” (Bey et al., 2020; see Sect. 1.2). Objectives for this program are included in Table 1.

2.1 Program description

The 3-year Climate READY program used original lesson plans developed by FAU Pine Jog staff and NOAA assets to strengthen community resilience and the adaptive capacity of participants in six underserved regions in Palm Beach County, Florida, as described in Sect. 1.3. The Sea Level Rise Viewer developed by the NOAA Office for Coastal Management allowed us to add social and economic data overlays (Fig. 1a), which identified three of the target regions (Riviera Beach, Lake Worth Beach, and the Glades) as red zones of high vulnerability, personal disruption, and risk (Sea Level Rise Viewer, 2023). The remaining regions, West Palm Beach, Boynton Beach/Delray Beach, and Boca Raton were highlighted as pink zones, demonstrating medium indicators of risk and social vulnerability. While these areas have undergone gentrification in sections near the Atlantic Ocean, extreme pockets of poverty and vulnerable populations still exist in these boundaries (Sea Level Rise Viewer, 2023). We targeted Title 1 schools in low socio-economic communities as defined by the Bureau of Federal Educational Programs and part of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) which identifies schools that have at least 60 % of their students living in low-income households (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019; Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability, 2021).

The Climate READY program included the development of the following three interconnected components that were divided into three-semester courses at FAU listed here and described in the subsections below:

-

Climate READY Ambassador Institute, offered as EDG 4930: Building Community Climate Resilience;

-

Climate READY After-school Program, offered as EDG 4930: Youth Mentorship in Climate Resilience;

-

Climate READY Community Outreach, offered as EDG 4930: Community Resilience Outreach.

The new three-semester program was implemented over two full cohorts, and a partial third cohort participated in a modified single-semester course in the summer of 2023. An advisory council of local resilience experts was established during the planning phase to provide feedback about the program. Using their advice, FAU Pine Jog staff used the first year of funding from October 2020 to May 2021 to establish an original curriculum for the three-semester dual-enrollment components. However, the global pandemic and temporary freeze of in-person classroom interaction required us to create an online learning approach for the first year of implementation from July 2021 to May 2022 (cohort 1). After restrictions were lifted in 2022, the Climate READY program was implemented with face-to-face interaction as originally designed during the second year of implementation from July 2022 to May 2023 (cohort 2). Using lessons learned from cohort 1, we revised the curriculum for cohort 2 and collected data as described in our “Research methodology” section (Sect. 2.2).

2.1.1 Climate READY Ambassador (CRA) Institute

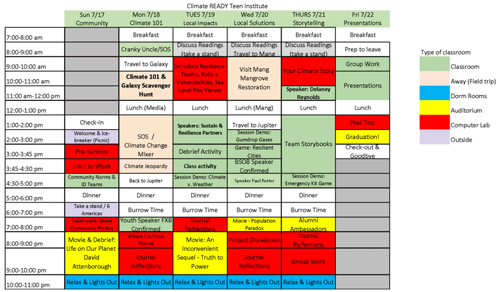

The Climate READY Ambassador (CRA) Institute was for 9th- through 12th-grade students, summer 2021 and 2022; semester 1. The summer course developed foundational climate literacy knowledge focused on current scientific research, implementation practices, and community resilience measures. Students ages 15 to 17 from underserved communities were prioritized in the recruitment process and were offered the opportunity to register as dual-enrolled (high school/university) students under a special topics course in FAU's College of Education. Students that had a strong application for the Climate READY program but did not qualify for dual enrollment at FAU were able to participate on a non-credit basis and received documented community service hours for completing the program. By design, the institute was created as an intensive 5 d residential program at the FAU John D. MacArthur Campus in Jupiter, Florida, which provided the opportunity for a deeper connection and immersion into the climate literacy/resilience content and a peer experience different from a traditional school-based setting. Field trips to Galaxy E3 Elementary School and MANG, a local mangrove nursery, were organized off campus to expose students to hands on experiences. However, due to the global pandemic and COVID concerns during the summer 2021 semester, students in our first cohort of students were not able to participate in the full in-person residential experience. We transitioned from a residential to a hybrid model for the CRA Institute, having planned the first and last Saturdays as extended in-person days at Galaxy E3 Elementary School in Boynton Beach and at FAU Pine Jog in West Palm Beach, respectively. Classes Monday through Friday during that week were shorter virtual days using Webex. With restrictions lifted in summer 2022, student participants in the second cohort, our experimental group, were able to attend the originally designed in-person residential model (Table 2).

Table 2Schedule of activities and lessons implemented during semester 1 of the Climate READY program (July 2022), a week-long residential college course designed for dual-enrolled high school students, the Climate READY Teen Institute. For the exception of two field trips to Galaxy E3 Elementary School and MANG nursery (tan), classrooms (green) were within walking distance to dorms (blue) and dining hall (white) where vegan and vegetarian options were given during all meals (PNG file).

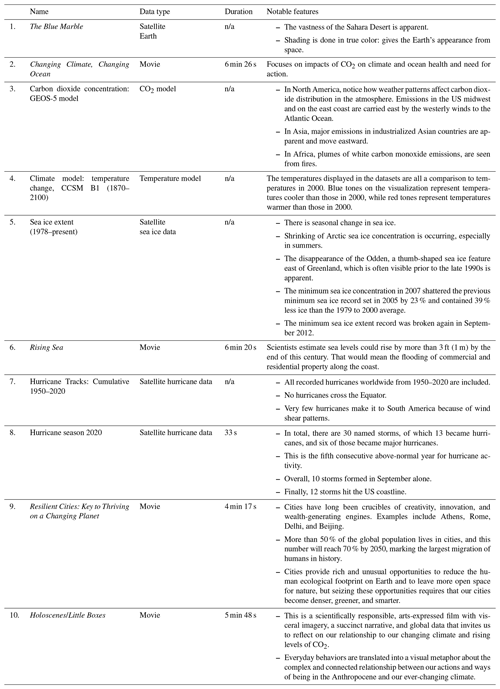

Climate science was taught in part by NOAA's Science on a Sphere (SOS) technology in collaboration with Galaxy E3 Elementary School (Galaxy E3), a Title 1 public school (see definition in Appendix A) with platinum-level LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design; see definition in Appendix A) certification (Kubba, 2009), serving a primarily low socio-economic population in Boynton Beach, Florida, vulnerable to climate change (Fig. 1). Galaxy E3 is a unique school that received generous community donations to rebuild after their old school, which was condemned and demolished (Storyology Studios Presents: Galaxy E3 Elementary School, 2015). The majority of the students in regular attendance at Galaxy E3 are ages 5 to 11 and live at or below the poverty line (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2024; and see definition in Appendix A). The school was specifically chosen to be a partner in the FAU Climate READY program due to its success as a top-tier-rated (platinum) LEED-certified facility that implemented environmentally sustainable methods during construction while also featuring nontraditional teaching tools such as NOAA's SOS technology (U.S. Green Building Council Inc., 2024). In addition, FAU Pine Jog program coordinators and staff have worked with teachers and staff at Galaxy E3 over the years on numerous occasions, and professional connections were in place prior to this project's inception. NOAA's SOS technology was used to help facilitate our Climate 101 lessons. The SOS uniquely projects seamless imagery on a sphere-shaped projection screen that is 6 ft (1.83 m) in diameter and suspended from the ceiling of a dedicated room. It has shown to effectively enhance student learning of weather and climate concepts using global-scale Earth system science (Rowley et al., 2013), which is in line with the concept of using geospatial visualizations to enhance climate science literacy (Hestness et al., 2014; Niepold et al., 2008; Wolf-Jacobs et al., 2024). We created a SOS playlist for the students using data provided by the NOAA SOS datasets (Science on a Sphere Dataset Catalog, 2023; see Appendix B, Table B1). This playlist was an important part of teaching climate change science as it provided visual representations of global carbon dioxide concentrations, global temperature, global hurricane pathways, and changes in Arctic sea ice coverage over time. A few of the video shorts created by NOAA partners that were included in the NOAA SOS datasets were also shared. In using the SOS, students were able to connect what they learned about the causes and effects of climate change with visual global patterns through time, which reinforced concepts such as the difference between climate and weather, patterns of greenhouse gas emissions and temperature changes, and how communities can work together towards a common goal. Teen participants in the CRA Institute would later use the SOS with younger (after-school) students in the fall semester.

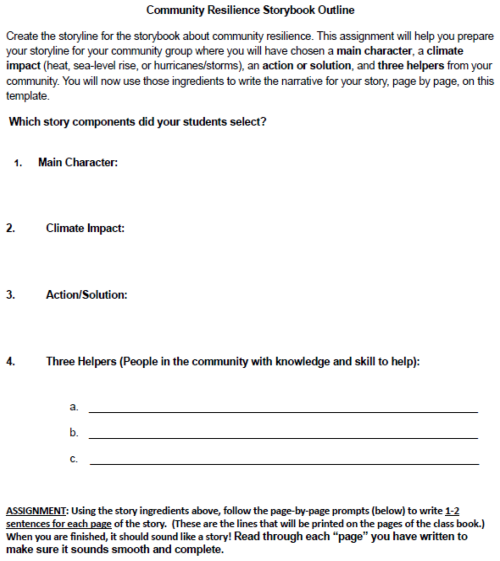

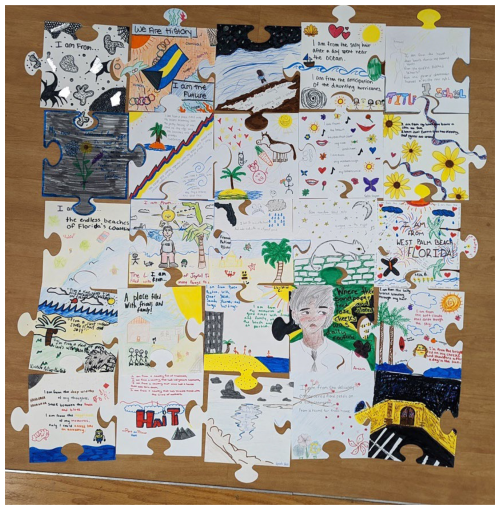

Throughout the week-long summer course, CRA Institute students connected with sustainability officers, scientists, researchers, and representatives from the local government and the RCAP community. Using place-based active learning strategies, this institute focused on anthropogenic issues impacting south Florida, such as sea level rise and extreme weather events. Lessons delivered included using a case study approach, where participants evaluated the risks, assets, and vulnerabilities of their local municipality and explored inequities produced by current systems. Major assignments for students during the summer component included a Photovoice project to help students connect with their communities (Photovoice, 2023; Science, Camera, Action!, 2023), a poem titled Where I'm From and puzzle piece class project (Christensen, 2001; see Appendix B, Fig. B1), the creation of their own “climate story” (Discover Your Climate Story, 2006; example in Fig. 8b), and a team assignment to create a storybook using an original template created by FAU Pine Jog (see Appendix B, Fig. B2). The storybook lesson was important to help connect with the younger students in the after-school component during semester 2. In both cohorts, students that had completed the 80 h program were equipped as Climate READY Ambassadors (CRAs) that were responsible for delivering the second component, the Climate READY After-school Program.

2.1.2 Climate READY After-school Program – youth mentorship

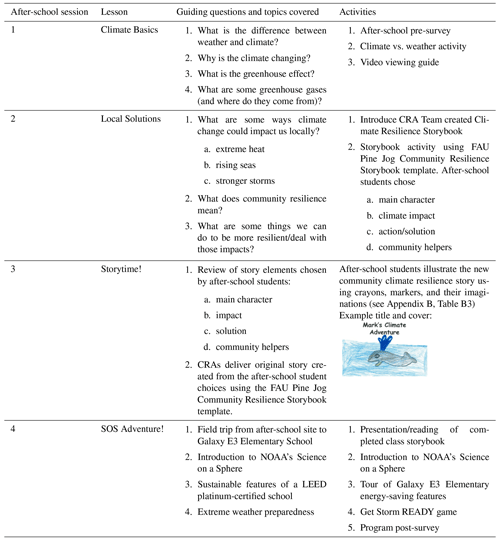

The Climate READY After-school Program was designed for the 9th- to 12th-grade students (ages 15–17) that completed the CRA Institute the previous summer, naming them CRAs, in semester 2. These students worked as mentors to fourth- through fifth-grade after-school students (ages 9 to 11) while enrolled in FAU College of Education's Youth Mentorship in Climate Resilience in the fall semester immediately following the summer semester for each cohort. Students were given the option to take the course as a dual-enrolled student or for community service hours as a non-credit course. FAU Pine Jog staff met with the class during five 4 h online classes using Webex or Google Meets on Saturday mornings throughout the semester and a final all-day in-person class to conclude the course and participate in a field experience. The CRAs were also required to meet with their after-school groups. This course was created as the second part of the three-semester Climate READY Program to connect with local elementary after-school programs where students delivered grade-level-appropriate climate resilience activities using four detailed 60 min sessions aligning with Florida State standards (CPALMS, 2024); Session 1‚, Climate Basics; Session 2, Local Solutions; Session 3, Storytime!; and Session 4, SOS Adventure! (Table 3).

Table 3Climate READY after-school lessons and activities implemented by the cohort 2 CRAs during the fall semester (2022).

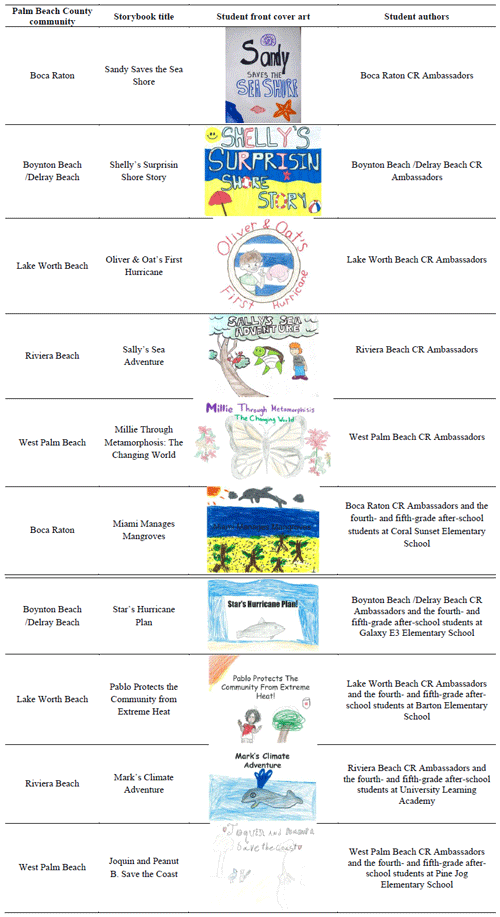

Guided by educational professionals from FAU Pine Jog, CRAs worked in teams of four to five to deliver over 4 h of programming to up to six after-school sites in Palm Beach County during each program cycle. After-school programs that targeted underserved communities were given priority in the recruitment process. Activities focused on gaining a conceptual understanding of basic climate processes, potential impacts, and local resilience initiatives that are already in place and empowering all students through action by creating a storybook focused on community-specific needs (Table 3). The CRAs used an original template created by FAU Pine Jog to assist the fourth- and fifth-grade after-school students ages 9 to 11 in developing an illustrated storybook of their own, which highlighted how their community could be resilient to climate change (see Appendix B, Fig. B2). The original storybooks were printed and bound through an online company, DiggyPOD (DiggyPOD, 2004; see Appendix B, Table B3), and distributed to the after-school students and CRAs that participated in the program to take home and share with their families. Any extra books were given to the participating school to share in their school or classroom libraries. The culminating Lesson 4 provided transportation for all students to visit Galaxy E3 Elementary School in Boynton Beach, Florida, to learn about how the school achieved platinum-level LEED certification and for the students to experience standards-based content on NOAA's SOS technology. Lastly, a FAU Pine Jog original game called Get Storm READY was used to help teach students the importance of preparing for a hurricane and gave them time to think about what items may be important when creating a hurricane preparedness kit for their families (Fig. 7c).

2.1.3 Climate READY Community Outreach

The final semester of the Climate READY program was for the community at large and delivered by CRAs in the spring of 2022 and 2023, i.e., semester 3. It included the FAU College of Education's Community Resilience Outreach course. Similarly to previous semesters, the CRAs were given the choice to take the course for dual-enrollment credit or for no credits and receive community service hours. FAU Pine Jog staff met with the class during five 4 h online classes using Google Meets on Saturday mornings throughout the semester and a final all-day in-person class to conclude the Climate READY program and participate in a field experience. This component of the program emphasized building knowledge and skills to implement the climate resilience education curriculum and activities within local communities (Table 1). The design of this course was informed by the NOAA Community Resilience Education Theory of Change, which outlines the goals of community resilience education (Bey et al., 2020; see Sect. 1.2).

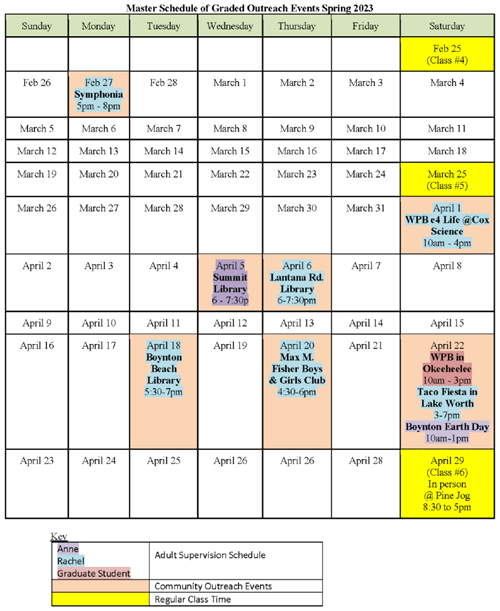

Lessons also addressed social emotional learning as well as time management practice to help better prepare our youth for public speaking and to help them with time commitments (see Appendix B, Fig. B2). The Climate READY Ambassador teams were required to create a community resilience plan tailored to their assigned communities. The CRAs researched their assigned community's assets, strengths, and vulnerabilities and then recommended at least three possible solutions to help solve the issues their communities are facing with the threat of climate change. Each team was then required to present their resilience plan by participating in two presentations to members of their respective communities. One presentation needed to be a formal lecture and discussion-style presentation using the PowerPoint or Google Slides format, while the second presentation could be a table event at a festival or fair. Each presentation focused on a community resilience plan that included CRA research on place-based needs to achieve climate resilience throughout the three-semester program. In their presentations, CRAs outlined how their communities could be more resilient to the impacts of climate change, strengths of their respective communities, and potential solutions to help mitigate and/or adapt to impacts. FAU Pine Jog instructors coordinated the outreach events for cohort 2 in the spring semester (see Appendix B, Table B2). Graded time management lessons were designed and implemented during class time for the dual-enrolled students to teach them the importance of scheduling and keeping commitments.

Overall, 4 of the 13 graded outreach events during cohort 2 were not on this student schedule. These events were planned and implemented prior to this time management assignment (see Appendix B, Table B2). Events included three Urban Sustainability Directors Network (USDN) grant collaborations with the Palm Beach County Office of Resilience, where students interacted with members of the community in Pahokee, Belle Glade, and West Palm Beach (Amplifying Impact Community Partners of South Florida, 2023; Fig. 8a–c). The fourth event, Climate and Art, was coordinated by the Delray Beach Office of Sustainability and Resilience. Students in the Boynton Beach/Delray Beach Team shared the storybook they created during the summer CRA Institute with the Delray community (Climate and Art Delray Beach, 2022).

2.2 Research methodology

Using lessons learned from cohort 1, we revised the curriculum for cohort 2 and collected data using a pre-questionnaire in the beginning of the Climate READY Institute (July 2022) and a post-questionnaire after the Climate READY Institute in July 2022 (Post 1), and we repeated the post-questionnaire at the end of the last-semester course that focused on community outreach in May 2023 (Post 2). The three data points were used to assess learning outcomes and retention of content throughout the three-semester program and to test our hypothesis in this study.

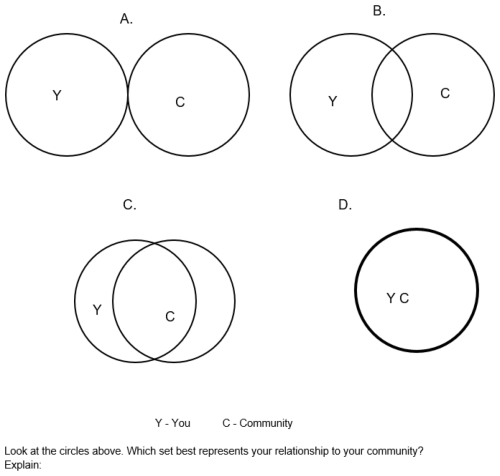

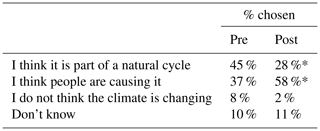

The CRAs were also given pre- and post-assessment questionnaires where they were asked to describe the degree of their connection with their communities using circles to represent their sense of place within a community (Fig. 2) and to evaluate self-efficacy. The circle labeled Y represents the student, and the circle labeled C represents their community. These circles were shown in four different settings, representing the degree of closeness between self and the community. The CRAs were asked to indicate which setting best represented them followed by space for the student to explain why they chose that setting.

Figure 2Survey question using circles to represent sense of place within a community. The circle labeled Y represents the student, and the circle labeled C represents their community. Adapted from Petersen et al. (2020).

2.2.1 Curriculum evaluation

The evaluation utilized a mixed-method approach focused on measuring changes to participant behaviors, attitudes, skills, interests, and knowledge (BASIK) (Creswell, 2015; Davis et al., 2019; Frechtling et al., 2010). Participants within this study included the cohort 2 CRAs that completed the three-semester dual-enrollment program with FAU Pine Jog during the academic year from July 2022 to May 2023. Summary reports as well as an annual report were filed after each phase of the program presenting both formative and summative findings and offering recommendations to the NOAA grant co-principle investigators to FAU Pine Jog program coordinators and supporting staff.

2.2.2 Pre- and post-assessment questionnaires and surveys

A questionnaire was created by the writers of this paper with 32 content knowledge questions to assess CRA awareness of climate change science. Many of the questions came from the Climate Literacy Quiz published by the Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network (Climate Literacy Quiz, 2018). Additional resources for content knowledge questions included texts used in high-school- and college-level environmental science and management courses (Butz, 2008; Myers and Spoolman, 2014; Friedland and Relyea, 2015). Using Global Warming's Six Americas as a gauge, CRAs were asked to share their perception of climate change ranging from dismissive to alarmed (Maibach et al., 2011). Pre- and post-assessment surveys were also used to ask CRAs to describe their connection with their communities using circles to represent their sense of place within a community (Fig. 2) and to evaluate self-efficacy. We collected information on the demographics of student participants, such as age, gender, race, and grade level.

A modified pre- and post-assessment questionnaire was also created for the after-school students; one pre-assessment questionnaire was given before Lesson 1 in the after-school mentorship component, and an identical post-questionnaire was given at the end of Lesson 4. This survey contained fewer questions with simpler language to target after-school student learners. It was given anonymously, so no identifiers of name or location were asked.

2.2.3 Data analysis

Climate READY Ambassador (CRA) responses to pre- and post-assessment questionnaires were categorized into appropriate groups based on individual responses to each question, and the responses were then summarized (N=22 matched pairs). The CRA numeric responses were summarized, and appropriate matched-pair statistical analysis (Student's t test) was applied. The CRAs' scored responses to pre- and post-assessment questions were then analyzed for comparison using a two-sample t test when data followed the normal probability distribution and the non-parametric Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test when the probability distributions were non-normal. Open response items were analyzed with kernal analysis and summarized. The significance level (α value) was set to 0.05, and results were considered statistically significant if p<0.05.

In a separate analysis, the after-school student responses were anonymous and the mean values for the pre- and post-assessment questionnaire followed the normal probability distribution. Mean values for pre- (N=60) and post-assessment (N=52) questionnaire were analyzed for differences using Student's t test (p<0.05).

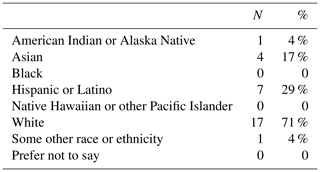

Data were collected and analyzed using the methods as described in Sect. 2 for cohort 2 (July 2022 to May 2023). Although FAU Pine Jog staff spent time recruiting students in the Pahokee/Belle Glade area for cohort 2, no student from that area completed the application process. This contrasted with cohort 1, where six students from Pahokee/Belle Glade were active CRAs. Therefore, for cohort 2, we focused on the five remaining communities of Boca Raton, Boynton Beach/Delray Beach, Lake Worth Beach, West Palm Beach, and Riviera Beach (see Fig. 1b). A total of 22 matched-pair responses were summarized for the Pre and Post 1 data. In total, 20 responses were summarized for the Post 2 data. Most CRAs (96 %) were between 15 and 16 years of age and female (72 %), 55 % of the CRAs described themselves as White, 36 % as Hispanic or Latino, and 18 % as Black. The CRAs were going to be in 10th (32 %), 11th (41 %), and 12th grades (27 %), and they reported learning about climate change from school (), internet and social media (), and television () primarily.

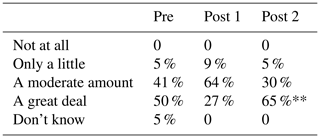

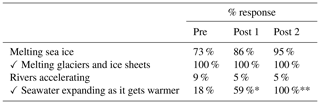

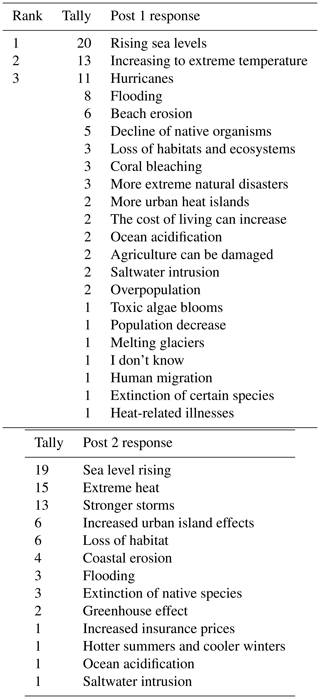

Upon the completion of the three-semester course experience with FAU Pine Jog, CRAs felt significantly more connected with their communities and more confident in communicating their knowledge to public groups (Table 4). After their experience, they were statistically more likely to feel alarmed about climate change (Table 5), and significantly fewer CRAs reported that they do not question climate change (see Appendix C, Table C3). The CRAs showed significant improvements on 23 of 32 content knowledge items from Pre to Post 1 with high pre-assessment questionnaire scores on seven items leaving no room for significant improvement (see Appendix C, Tables C4–C16). When asked to identify some of the impacts of climate change affecting south Florida, after the experience, CRA responses were more detailed and factual and considered multiple areas of impact (see Appendix C, Tables C15 and C16).

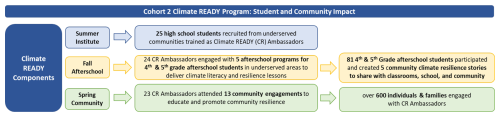

3.1 Community impact and student perception of climate change

Over 700 community members were impacted during cohort 2 (Fig. 3). In total, 25 high school students were recruited for the dual-enrollment summer session Climate READY Teen Ambassador Institute to become Climate READY Ambassadors (CRAs). Furthermore, 24 of the CRAs returned for the fall-semester after-school mentorship course where CRAs led five after-school programs located in underserved communities and designated as Title 1 (Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability, 2021). Furthermore, 81 after-school students ages 9 to 11 participated in the CRA led climate change resilience lessons and produced five community resilience stories. These stories were made into printed books and given to all student authors (CRAs and after-school students) and school administrators for classroom distribution as described in our methods (see Appendix C, Table B3). Also, 23 CRAs returned for the final spring-semester course and led a total of 13 community outreach engagement events, impacting over 600 individuals and families within their communities.

Figure 3Over 700 community members including high school and elementary school students were impacted during cohort 2 of the Climate READY program between July 2021 and May 2022.

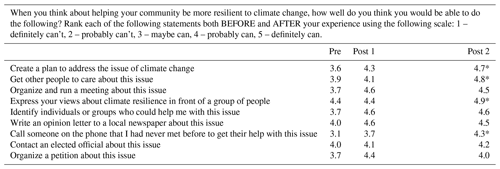

When CRAs were asked to describe their connection with their communities using circles to represent their sense of place within a community (Fig. 2) they detected a significant (p<0.05) increase between pre- and post-assessment survey responses, indicating that CRAs felt closer to their communities after the three-semester Climate READY Program. Space was given for a written explanation (Fig. 2), and one CRA stated, “I believe C best represents my relationship with my community, which has changed as it was originally B. I feel a lot more involved with my community after all the civic engagement projects I did with Climate READY and at school.” Another CRA reported, “I believe that C best represents my relationship to my community since I did many events that built the relationship. For example, the climate presentation I did over at the Lantana Road Library allowed me to connect to the fellow residents of Lake Worth as I got to share [with] them my experience with climate change.” The CRAs also reported feeling their community was very special to them, that they like to visit places in their community, and that their community means a lot to them. By the end of the three-semester program, more CRAs felt confident in helping their communities be more resilient to climate change (Table 4).

Table 4Climate READY Ambassador students (CRAs) felt more confident in communicating climate change and resilience in front of a public group by the end of the three-semester program.

* Indicates a significant difference between Pre and Post (p<0.05).

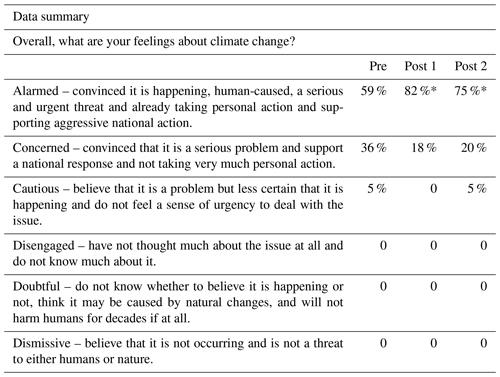

Out of the 23 CRAs in cohort 2, 22 completed all three pre- and post-assessment questionnaires over the course of the three-semester program. To help gauge student perception of climate change, CRAs were asked, “Overall, what are your feelings about climate change?”, and the Global Warming's Six Americas was given as an answer option to choose from (Maibach et al., 2011). Significantly more CRAs (p<0.05) felt alarmed after the week-long CRA Institute in summer 2023 and significantly fewer CRAs (p<0.05) felt alarmed after the completion of the three-semester program (Table 5).

Table 5Significantly more Climate READY Ambassador students felt alarmed about climate change from Pre to Post 1 assessment, with a 7 % decrease in feeling alarmed by the end of the three-semester program.

* Indicates a significant difference between Pre and Post (p<0.05).

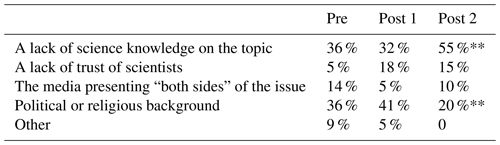

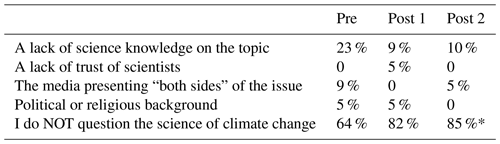

When asked if they think their community is already being affected by climate change, CRAs reported a significantly greater perception of “a great deal” throughout the course of the program. In addition, they thought that a lack of science knowledge on the topic was the main reason that people question climate change and that after completing the three-semester program, 85 % of the CRAs said they “do NOT question the science of climate change” (see Appendix C, Table C3).

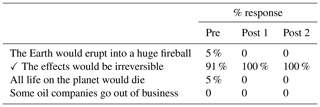

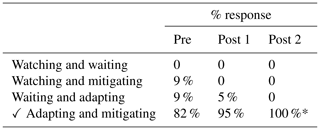

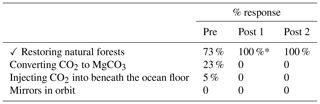

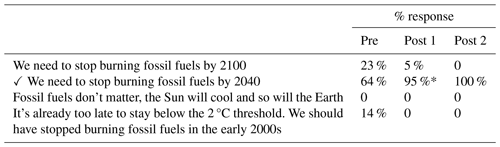

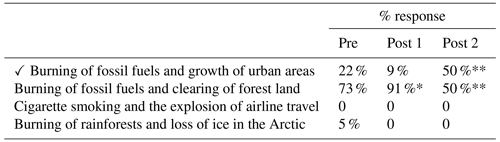

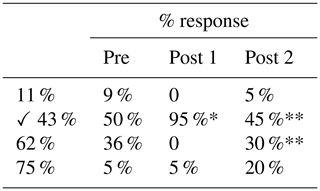

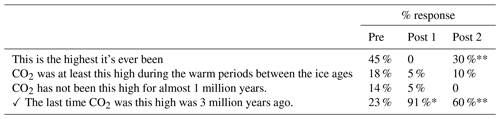

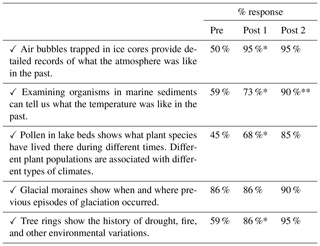

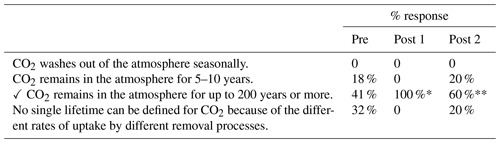

3.2 Climate READY Ambassador student climate change content knowledge Pre, Post 1, and Post 2 questionnaires

The CRAs showed improvement in their understanding of climate change science throughout the three-semester program (see Appendix C, Tables C4–C16). The CRAs were asked the following question: “If the greenhouse effect is natural, then why today's climate change a bad thing? (select all that apply)”, and significantly more (p<0.05) CRAs responded with correct answers during the Post 1 questionnaire (see Appendix C, Table C4). Interestingly, 100 % of CRAs responded correctly to four items of the same question during the Post 2 questionnaire, though it was not a statistically significant difference (see Appendix C, Table C4). More CRAs understood that a major concern about climate change is that if CO2 levels in the atmosphere exceed 450 ppm, the effects would be irreversible (see Appendix C, Table C5). The CRAs also understood that our best approaches to climate change are adapting and mitigating (see Appendix C, Table C6), that restoring natural forests would be the best carbon sequestration strategy with the highest probability of success (see Appendix C, Table C7), and that we need to stop burning fossil fuel before 2040 as research indicates (see Appendix C, Table C8) (Climate Literacy Quiz, 2018; Maniatis et al., 2021).

The CRA responses to six content knowledge items on the Post 2 questionnaire were significantly different from those on Post 1 (p<0.05) (see Appendix C, Tables C9–C13). These changes in responses suggest that the CRAs continued to develop their climate science knowledge throughout the year and their engagement with the Climate READY program. The CRA answers were more detailed and factual during Post 1 and more concise in Post 2, with the top three answers being sea levels rising, extreme heat, and stronger storms/hurricanes in both (see Appendix C, Table C15 for ranked tallies of CRA responses and Table C16 for detailed CRA responses). They also showed a more scientific understanding of climate change in the south Florida area (see Appendix C, Tables C15–C16).

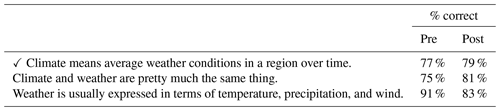

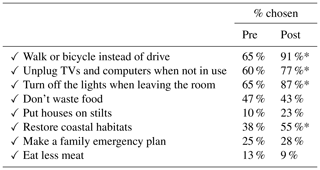

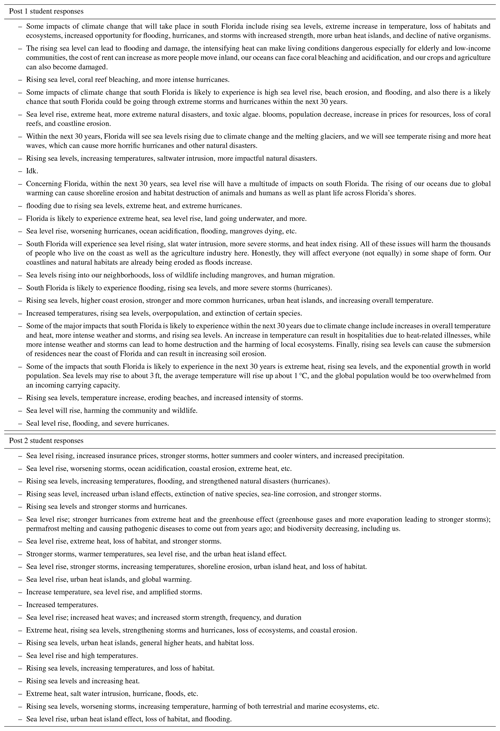

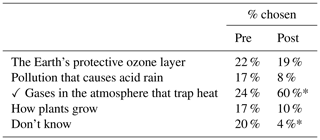

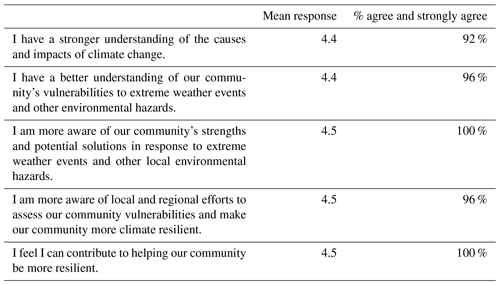

3.3 After-school student pre- and post-assessment questionnaire results

A total of 60 after-school student learners ages 9 to 11 completed the pre-assessment questionnaire before the Climate READY Ambassador-led Lesson 1 and 53 completed the post-assessment questionnaire after Lesson 4 (see methods). Significantly fewer after-school students reported being “not at all” worried about climate change after their experience. Significantly more after-school students felt that people were causing climate change after their experience, with fewer feeling it was part of a natural cycle (see Appendix C, Table C17). Significantly more after-school students correctly identified the greenhouse effect as being gases in the atmosphere that trap heat after their experience (see Appendix C, Table C19). Significantly more after-school students understood that extreme heat and rising seas are ways that climate change could affect south Florida after their experience (see Appendix C, Table C20). After-school students were significantly more able to identify ways to help reduce climate change, including walking or riding a bike in place of driving, unplugging TVs and computers when not in use, turning off lights when leaving a room, and restoring coastal habitats (see Appendix C, Table C21). No significant changes were found in how the after-school students felt about being able to solve problems in their community, knowing how to make their community a better place, feeling like they can make a difference in their community, and feeling like they can make a difference in protecting the environment.

The three-semester model for teaching and training high school dual-enrolled students at FAU Pine Jog to be Climate READY Ambassadors has proven to be an effective way to empower our youth and to engage the community in climate resilience education and action. In its second year of implementation, the Climate READY program was able to provide a pathway for 23 Climate READY Ambassadors ages 15 to 17 to participate in the global youth climate movement (Cloughton, 2021) and reach as many as 700 local south Florida community members of all ages.

4.1 Program objectives

4.1.1 Objectives for all students

The program focus was to build environmental literacy of 4th- through 12th-grade students ages 9 to 17, teachers, and the public so they are knowledgeable about south Florida's changing climate systems, ways in which their community can become more resilient to extreme weather and/or other environmental hazards, and how they can become involved in achieving that resilience (Table 1). The Climate READY program accomplished this by creating and implementing a comprehensive three-semester dual-enrollment opportunity for high school students in Palm Beach County (the CRAs) as described in our methods. The CRA coursework and feedback through pre- and post-assessment survey questionnaires demonstrated an increase in CRA understanding of climate change (see Appendix C, Tables C1–C14; p<0.05), and CRA responses to identifying impacts on Florida were more detailed, factual, and considered multiple areas of impact (see Appendix C, Tables C15–C16). The most significant changes came as CRAs gained more experience as Climate READY Ambassadors (CRAs). From summer to spring, they became more aware of the effects of climate change on their communities, shifted their thinking about the reasons people question climate change to be more focused on the science and less on politics or religion, and increased their knowledge about key concepts associated with climate change and climate resilience.

4.1.2 Objectives – summer 2022 Climate READY Ambassador Institute

The first semester (summer 2022) worked through objectives (Table 1) that increased student content knowledge of the science of climate change (Table 2); improved critical thinking skills to assess the sources of different climate change perspectives and attitudes; highlighted local impacts within south Florida (see Appendix C, Tables C15–C16); explored possible local solutions (i.e., mangrove restoration with MANG; Table 2; Fig. 4); met professionals that work towards equitable solutions, such as those within the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact (2022; Table 2); and provided a starting point for students to communicate this knowledge through creating storybooks (see Appendix B, Table B3).

Figure 4Climate READY Ambassador students participating in a service-learning field activity with MANG nursery in West Palm Beach, Florida, in the summer of 2022. Co-founder Keith Rossin taught students how mangroves are used in coastal restoration and guided them through methods to grow and plant them.

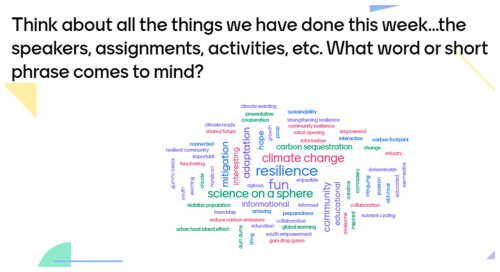

In addition, the Climate READY program successfully established relationships between CRAs across Palm Beach County through the in-person residential summer-semester course. On the last day of the class, CRAs were asked the following in an informal setting: “Think about all the things we have done this week… the speakers, assignments, etc. What word or short phrase comes to mind?” The image was created using a word cloud generator (Mentimeter, 2023) where words become larger when used multiple times. The final image indicated that the largest and most used words were fun, resilience, climate change, and Science on a Sphere followed by community, adaptation, and mitigation (Fig. 5). Many other words were added to create a large word cloud that represented the wealth of information they received from the course and, most importantly, to reinforce the evidence in the survey results that the information was retained. This was all while CRAs reported to have “fun”, indicating that they not only learned through the experience, but that it was also enjoyable. The use of fun activities in the learning environment is often used with younger students, though previous research indicates that it can be used with all age groups and that experiencing fun and enjoyment can be “identified as a proven way to build a socially connected learning environment” (Lucardie, 2014), which can make a lasting impression on a learner and help them retain information. This is also seen in storytelling lessons (Miley, 2009).

Figure 5Word cloud (Mentimeter, 2023) used to generate a visual representation of student perception of the summer semester 2022, the first of the three semesters in the FAU Climate READY program.

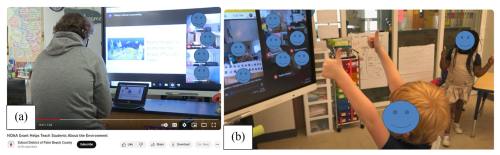

Storytelling has been used in communicating scientific concepts including climate change (Coren, 2020; Moezzi et al., 2017), and research has shown that storybooks can be used to bring communities together (Peters, 2024). For example, one way to teach students how to communicate complex concepts such as climate change is by creating and sharing storybooks with elementary school students. This idea came from a 4-year collaboration with students from Boca Raton Community High School in Boca Raton, Florida, and Galaxy E3 Elementary School in Boynton Beach, Florida, within the Palm Beach County School District, a public school system (Fig. 6) while mentored by retired environmental science teacher Barbara Riley. In 2018, high school students were given an assignment to create a storybook of an ecological issue as part of an Advanced International Certificate of Education (AICE) Environmental Management course (Cambridge International AS Level Environmental Management – (8291), 2022). The purpose of the lesson was for high school students ages 15–18 to research an ecological issue of choice and to identify the main causes, effects, and possible solutions. The exercise required these students to break down complex issues into smaller digestible units that could be easily described to an elementary school student (ages 5 to 11). At the same time, creative freedom was given, which gave the high school students an opportunity to gain confidence in communicating the subject. As part of the course, these high school students took a field trip to share their stories with kindergarten through second-grade students at Galaxy E3 Elementary School, where the high school students became the teachers. While at Galaxy, students were also exposed to another form of storytelling through NOAA's SOS technology to reinforce Earth system science concepts they were teaching earlier that day. Due to a successful first year of implementation, the collaboration continued for an additional 3 years, until spring 2022, with a virtual year in 2020 during the global pandemic (Fig. 6; NOAA Grant Helps Teach Students About the Environment, 2021).

Figure 6AICE Environmental Management student from Boca Raton Community High School (a) sharing their ecological storybook project with kindergartners at Galaxy E3 Elementary School (b) (NOAA Grant Helps Teach Students About the Environment, 2021).

Classroom surveys were conducted to analyze student feedback, and although the results of the 4-year program are not currently published, the testimonials of both elementary and high school students were noted and used to improve the lesson for the AICE course. One student reported, “Whatever you do, keep the storybook activity and field trip to Galaxy. I will never forget my experience with the little kids” after being asked for feedback about the overall course. The storybook lesson impacted everyone involved, including the students, teachers, volunteers, and administrators. One teacher reported, “This experience gave me goosebumps!” and “I even learned something new today.” The storybook lesson brought the community together and it gave them a safe space to talk to each other about environmental issues and solutions. Training teenagers (15 to 18 years old in this case) as teachers can have lasting effects on student confidence and character growth (Worker et al., 2019). The Climate READY program took this idea a step further by creating a unique storybook template that highlights climate change in the local community (see Appendix B, Table B3; Fig. B2). The CRAs created team stories during the first semester to help them understand the meaning of climate change resilience and to help them connect with the issues their communities are facing. It was used as a final project grade. These stories were then shared in the second-semester after-school program as part of the lessons given to after-school students in the same community as described in our Methods section. Similar sentiments from CRAs indicate growth and confidence in communicating climate change, which helped prepare them for the third semester of community resilience outreach.

4.1.3 Objectives – fall 2022 Climate READY After-school Program

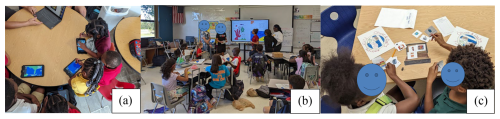

During the fall semester (2022), CRAs learned to teach a four-lesson after-school program that brought students together to investigate the complex issue of climate resilience as a team (Table 3; Fig. 7a–c). This provided a safe space for students to talk about the challenges they face in their own community. For example, the Lake Worth Beach team learned that one of their after-school students at Barton Elementary School experienced a heat stroke during school hours earlier that school year. Although the after-school student was given immediate medical attention and they were alright and able to share their story, this was a traumatic event that affected the entire school population. Our CRAs used this personal story to discuss how climate change effects such as extreme heat can cause health problems like heat exhaustion or heat stroke and that the dangers are real for their community (The Fifth National Climate Assessment, 2023; Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact, 2022; U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2016). When it was time to create a new climate resilience storybook, the Barton Elementary after-school students decided to write a storybook about extreme heat, Pablo Protects the Community from Extreme Heat (see Appendix B, Table B3), which addressed the program objective for fourth- and fifth-grade after-school students to design and complete a storybook on community resilience to build an understanding of climate change and the impacts southeastern Florida is facing (Table 1). The personal experiences from the after-school students helped them consider solutions, and with the help of the CRAs and the training they received through the Climate READY program, after-school students chose to plant trees to create more shade, decreasing the heat island effect and reducing risk of heat-related illnesses. In their storyline, a gardener, a tree caretaker, and everyone from their community worked together to plant trees throughout the community. In the end, they celebrated with an ice cream party, and everyone was protected from the dangers of heat exhaustion and heat stroke. Even though the CRAs were the teachers in this setting, they were also learning from the elementary school students through this student community engagement activity, an important tool in training future leaders (Millican and Burner, 2011).

Figure 7After-school students participating in the Climate READY program. NOAA's Science on a Sphere and mobile application was used to help students understand climate change and how it relates to the effects seen in Florida (a). Climate READY Ambassadors were the teachers of four lessons, including the creation of a storybook (b), and students were given a hurricane resilience game called Get Storm READY to help them decide what might be the best items to pack in preparing for stronger storms (c).

Pre- and post-assessment surveys were given to the after-school students before and after the four-lesson program (see Appendix C, Tables C17–C21). In total, 60 learners (N=60) completed the Pre survey, and 53 completed the Post survey. The results indicate that significantly (p<0.05) more learners understood the science of the greenhouse effect, that humans are causing the current climate change we are witnessing, and that extreme heat and rising seas are ways that climate change could affect south Florida, and they were able to identify ways to help reduce climate change (p<0.05), including walking or riding a bike in place of driving, unplugging TVs and computers when not in use, turning off lights when leaving a room, and restoring coastal habitats, the last being somewhat unexpected (see Appendix C, Table C21). From classroom experience, many of our underserved youth in Palm Beach County have claimed to have never been to the ocean, let alone fully understand the dynamics of a coastline. It seems that their interactions with the CRAs helped them explore this ecosystem, and they recognized that ecological restoration projects like planting native mangroves along our coastline would improve community resilience to sea level rise and other effects of climate change (Su et al., 2021). Our CRAs experienced this with the in-service project at the MANG nursery in the summer (Fig. 4), and they communicated their experience with the younger after-school students. These outcomes from both groups of students are seemingly very successful, where students demonstrated learning by doing and/or learning by storytelling (Maccanti et al., 2023; Lawrence and Paige, 2016).

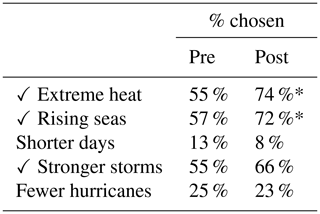

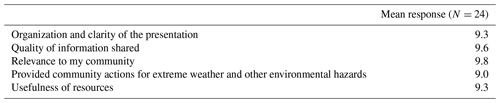

4.1.4 Objectives – spring 2023 Climate READY Community Outreach

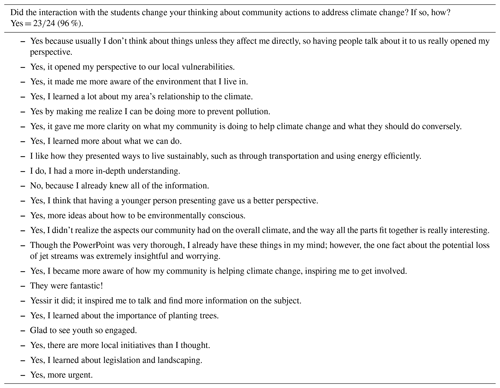

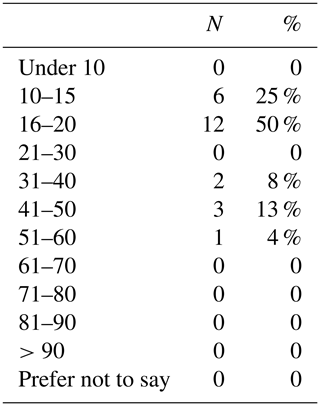

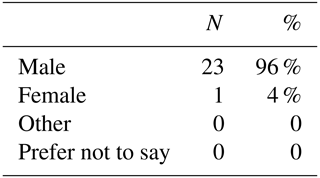

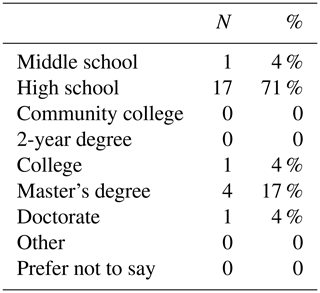

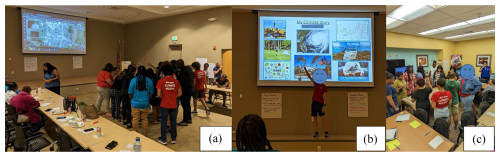

Similar to other community-based approaches to address climate change (Clark et al., 2023; Semmens et al., 2023; McNamara and Buggy, 2017; Uitto and Shaw, 2006), the Climate READY program reached out to the greater community during the spring semester. In the Community Resilience Outreach course, CRAs were given the task to generate a community resilience plan based on what they learned throughout the program and to present their plan during a community event. While targeting the objectives to identify and evaluate personal and community strengths and vulnerabilities in response to extreme weather events, acknowledge that disproportionate distribution of vulnerabilities and diverse community values exist, and design and implement community resilience-related service-learning projects based on local environmental challenges (Table 1), CRAs learned from local professionals throughout the program and developed community-specific resilience plans for each target community (Fig. 1). These plans were then shared with each community in at least two settings, one being a public presentation and another possibly a table event (see Appendix C, Fig. C5). Once again, the CRAs were the teachers for community members, adults, and families, addressing the objective to empower students to act as agents of change within the community by teaching community members about local climate impacts and resilience strategies for extreme weather events (Table 1). An optional survey was conducted for those community members that attended a presentation session with our CRAs, and we received 24 responses ranging from ages 10–15 to 51–60 (see Appendix D, Table D4). Most were male (96 %) and with varying levels of education (middle school to doctorate) (see Appendix D, Tables D5–D6). Community members (N=24) rated the organization, quality, relevance, and usefulness of the presentation with high averages of 9/10 or above (see Appendix D, Table D1). When asked the following: “Did the interaction with the students change your thinking about community actions to address climate change? If so, how?”, 23 out of 24 of the responses were yes (see Appendix D, Table D2). The responses included “usually I don't think about things unless they affect me directly, so having people talk about it to us really opened my perspective”, “I learned about legislation and landscaping”, and “I think that having a younger person presenting gave us a better perspective.”

The CRAs who participated in the table events were also well received, though a survey was not given. For example, our Lake Worth Beach team caught the attention of the current vice mayor, Christopher W. McVoy, a soil scientist and wetland expert, at an Earth Day Taco Fiesta event. Lake Worth Beach has not created an Office of Sustainability and/or Resiliency like the surrounding cities of Boca Raton, Boynton Beach, Delray Beach, and West Palm Beach, so the CRAs were captivated by his attention to climate change education, resilience, and youth involvement in the community. Much of their discussion focused on the need for their community to have a sustainability office in Lake Worth Beach local government and what steps the youth could take to encourage Lake Worth Beach to work towards a more informed community. Christopher W. McVoy shared his contact information, and the CRAs were excited to continue the conversation. Part of the hope for this program was that local governments would give these students (CRAs) a platform to share their perspectives and research on environmental issues much like Boca Raton has done with a youth subcommittee (Youth subcommittee puts words into action in Boca Raton, 2019). The interaction with Christopher W. McVoy was an excellent first step towards involving youth in local government for Lake Worth Beach; therefore, meeting active local government officials proved to be an important aspect of the Climate READY program. Another example where government officials interacted with our CRAs (outside of the course guest speaker encounters during class time) was through the Palm Beach County Office of Resilience (PBCOOR) and the Urban Sustainability Directors Network (USDN). The Director of PBCOOR, Megan Houston, and a Resilience and Sustainability Analyst, Natalie Frendberg, contacted our CRAs to participate in an USDN-funded project Strengthening Frontline Capacity for Climate Resilience Planning in Palm Beach County, Florida (Final Report 2023). Overall, 10 of our CRAs from our Boca Raton, Lake Worth Beach, and Riviera Beach teams represented Palm Beach County Youth in presentations involving community members in Belle Glade, Pahokee, and West Palm Beach (Fig. 8a–c). These CRAs were able to play active roles in climate resilience planning for these communities, further addressing the program objective to empower students to act as agents of change within the community by teaching community members about local climate impacts and resilience strategies for extreme weather events and influencing their sense of community (Table 1; Fig. 8a–c).

Figure 8Climate READY Ambassadors (CRAs) with the Palm Beach County Office of Sustainability participating in the USDN-funded project, Strengthening Frontline Capacity for Climate Resilience Planning in Palm Beach County, Florida (Final Report 2023). Students traveled to Belle Glade and assisted in determining community assets (a) and shared their climate stories with community members (b). The CRAs also interacted with community members in West Palm Beach (c).

4.2 Hypothesis analysis

Our hypothesis for the program was that participants in the Climate READY program will better understand their community strengths and vulnerabilities to a changing climate and that they will feel empowered to participate on both a personal and civic level to take action, minimize risks, adapt, and weigh the potential impacts of their decisions. We tested this hypothesis by designing and implementing a three-semester dual-enrollment program and using pre- and post-assessment questionnaires to compare means and identify significant differences (p<0.05). The mixed-method approach allowed us to focus on measuring changes to participant behaviors, attitudes, skills, interests, and knowledge (BASIK) and proved to be an effective tool in telling our Climate READY story. Through evidence, as discussed in this paper, high school students ages 15 to 17 that completed all three semesters, and all pre- and post-assessment questionnaires (N=23) were effectively taught climate change science and resilience (see Appendix C, Tables C1–C16), engaged in community settings to understand strengths and vulnerabilities (see Appendix C, Tables C1–C3; Figs. 5, 7–8), and felt empowered to take action and be more involved in community decision-making (Table 4; Fig. 8). In addition, the younger after-school students that took part in the four-lesson after-school part of the program and answered pre- (N=60) and post-assessment (N=53) questionnaires demonstrated an increased understanding of climate change, community resilience, and how they could contribute to being an active community member in combatting the effects of climate change (see Appendix C, Tables C17–C21). Although our sample sizes are relatively low (below 100), we feel that our results of this study support our hypothesis. We plan to make efforts to continue testing these hypotheses by providing this three-semester model to more youth in the community if our budget allows for it. We have hopes to extend our dual-enrollment (high school/university) opportunity to surrounding Broward, Miami-Dade, and Monroe counties. Finding funding is always a challenge.

4.3 Program challenges and recommendations