the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Planning virtual and hybrid events: steps to improve inclusion and accessibility

Victoria Dutch

Bridget Warren

Robert A. Watson

Kevin Murphy

Angus Aldis

Isabelle Cooper

Charlotte Cockram

Dyess Harp

Morgane Desmau

Lydia Keppler

The past decade has seen a global transformation in how we communicate and connect with one another, making it easier to network and collaborate with colleagues worldwide. The COVID-19 pandemic led to a rapid and unplanned shift toward virtual platforms, resulting in several accessibility challenges that have excluded many people during virtual events. Virtual and hybrid conferences have the potential to present opportunities and collaborations to groups previously excluded from purely in-person conference formats. This can only be achieved through thoughtful and careful planning with inclusion and accessibility in mind, learning lessons from previous events' successes and failures. Without effective planning, virtual and hybrid events will replicate many biases and exclusions inherent to in-person events. This article provides guidance on best practices for making online/virtual and hybrid events more accessible based on the combined experiences of diverse groups and individuals who have planned and run such events.

Our suggestions focus on the accessibility considerations of three event planning stages: (1) pre-event planning, (2) on the day/during the event, and (3) after the event. Ensuring accessibility and inclusivity in designing and running virtual events can help everyone engage more meaningfully, resulting in more impactful discussions that will more fully include contributions from the many groups with limited access to in-person events. However, while this article is intended to act as a starting place for inclusion and accessibility in online and hybrid event planning, it is not a fully comprehensive guide. As more events are run, it is expected that new insights and experiences will be gained, helping to continually update standards.

- Article

(787 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(565 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Diversity leads to better research and work outputs, helping to generate novel findings and perspectives (e.g. Beilock, 2019; Gomez and Bernet, 2019; Swartz et al., 2019; Hundschell et al., 2021). While diversity movements have historically focused on gender (typically binary) and ethnic background (see Golden, 2024), the more recent move to virtual platforms in 2020 has facilitated people connecting in a way that was never possible before. This also led to discussions on barriers to inclusion within geoscience, including consideration of fieldwork accessibility (Giles et al., 2020; Stokes et al., 2019; Greene et al., 2021; Pickering and Khosa, 2023), financial barriers (Abeyta et al., 2021), and parachute science, where international scientists conduct research without meaningfully engaging local communities and researchers (Ekandjo and Belgrano, 2022; Stefanoudis et al., 2021). These discussions have helped create new ideas and actions to overcome geosciences' historical lack of diversity (Dowey et al., 2021; Huntoon et al., 2015; Marín-Spiotta et al., 2020), creating a more inclusive and equitable field. However, one persistent challenge, impacting many people from different countries and backgrounds, has been accessing and attending international in-person conferences, which are fundamental opportunities to network and connect with other researchers from beyond typical geographic and disciplinary boundaries (Fleming, 2020). The dominance of purely in-person events has often resulted in the exclusion of historically marginalized groups from these spaces. As such, the recent evolution in virtual, online, and hybrid (events with both in-person and online elements) conferencing, as well as its impact upon accessibility and inclusivity in geoscience, merits renewed discussion.

While traditional in-person conferences offer many opportunities, they often present physical and mental challenges to participation for a wide range of people, including, but not limited to, those who are neurodivergent, have disabilities or chronic conditions, caring responsibilities, or family commitments (Chautard, 2019). For many researchers, events are too expensive to attend in person when registration fees, accommodation, transport, and other costs are taken into consideration (Sang, 2017; Vasquez, 2021; Wu et al., 2022; Amarante and Haag, 2024). Moreover, the predominance of in-person events held in the Global North increases the costs for many from the Global South and also reduces the opportunities and career progression options for many marginalized groups (Talavera-Soza, 2023). Researchers from the Global South often require visas to attend in-person conferences, which are often difficult and costly to obtain and require significant time in advance to arrange. Indeed, there have been numerous reported cases of researchers who were unable to attend in-person conferences to present their work simply because a request for a visa was either rejected or ignored completely (Chatterjee, 2022). Furthermore, cultural and political factors can also act to make in-person conferences inaccessible for minoritized researchers. Transgender and non-binary researchers may have problems travelling with a passport that does not align with their gender expression (Savage and Banerji, 2022). Additionally, using a passport with a neutral gender-marker (e.g. “X” on US passports) may cause issues if they are not accepted in the conference host country (Quinan and Hunt, 2021). The political and cultural climate of many countries is not one of inclusion for LGBTQIA+ people, with a lack of legal support creating unsafe environments for the community (Gibson et al., 2021; Olcott and Downen, 2020). In-person events may also lead to experiences of isolation, discrimination, and sexual harassment (Edig, 2020). Alcohol-focused social events may further exclude people from full participation and cause increased occurrences of sexual harassment and other inappropriate behaviours in professional settings (GRL, 2020). Consequently, virtual and hybrid events can provide advantages to foster more inclusive and accessible environments, encouraging participation from more diverse audiences and promoting a greater sense of belonging for all (Foramitti, 2021; Wu et al., 2022). Further, as many geoscientists are striving to travel less for environmental reasons, virtual options offer a potential alternative to reduce high carbon footprints associated with in-person attendance (Allen, 2022; Tao et al., 2021; Periyasamy et al., 2022).

In the last 10 years or so, but especially since the forced virtualization of many research activities during the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of virtual academic events has increased very rapidly (Graham, 2023); however, equity, diversity, inclusivity, and accessibility have, to a large extent, not featured in discussions around this virtualization. Indeed, many events previously hosted online (as a result of the pandemic) are now returning to fully in-person formats, often resulting in the exclusion of historically marginalized groups and many others who benefited from the previous change (Fraser et al., 2017; Niner and Wassermann, 2021). It is our view that (1) for global, interconnected networks to continue to grow and (2) to provide a more inclusive and accessible experience for a wider audience, virtual or hybrid events must continue to play a role in geoscience. Including virtual access to events makes them more inclusive and accessible, helping to share the content with more people, including those who are unable or unwilling to travel or are otherwise unavailable to attend physically. However, while virtual alternatives can be very positive, several challenges remain, including technological fatigue (Wiederhold, 2020), a lack of networking opportunities (King and Kovács, 2021), poor inclusion of the online audience in hybrid events (Eventforce, 2024), or a lack of access to a reliable internet connection (due to remote locations, poor infrastructure, or a lack of finances to purchase internet services; Signé, 2023). To counter these challenges, advanced discussion and consideration of accessibility during the pre-event, event, and post-event planning stages is crucial to avoid the inadvertent exclusion of people. It is not sufficient to simply include a virtual component as an add-on at the end. If we wish to make sure that online and hybrid events are truly inclusive and accessible, structures should be put in place early to ensure equitable experiences between virtual and in-person participants.

Here, we outline suggestions to help make online and hybrid events more accessible to a wider audience, based on the experiences of several groups and people involved with event planning for the virtual landscape as well on a wider search of the literature surrounding virtual events. This article is structured as follows: we first provide a summary of the existing literature surrounding accessibility, inclusion, and online or hybrid conferences; we then provide some guidance for each stage of running an accessible and equitable event, including Stage 1 (pre-event), Stage 2 (during the event), and Stage 3 (after the event). Some of these suggestions will depend on the size and type of event being organized, but they have been merged here to ensure that all elements are considered. While this article focuses on virtual and hybrid conferences specifically, our suggestions may be applicable to other events like seminars, workshops, and panel discussions. Many of us will be involved in organizing a virtual or hybrid event at some point in our careers, and ensuring it is accessible and inclusive for all requires some thought and planning. We acknowledge that this paper cannot give a full and finite description of making online and hybrid events more accessible and inclusive, as new techniques and strategies will evolve. As such, this article is only intended to act as a starting place and does not represent an ultimate guide to the accessibility needs of an event.

2.1 When did the shift to virtual events begin and how has this change manifested over time?

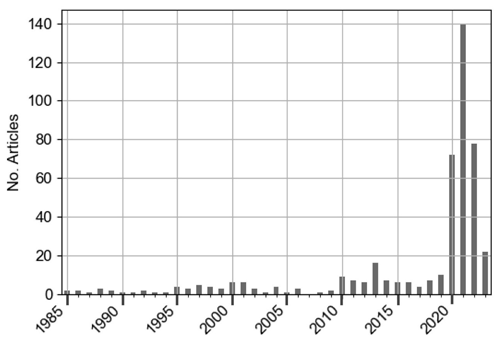

To quantitatively demonstrate changing interest in virtual conferences prior to and following 2020, we analysed records of literature indexed by the Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com/wos/, last access: 29 August 2023). We chose to limit our search to articles with the words “virtual”, “online”, and “conference” specifically in the title, rather than in the abstract text, as these articles are more likely to deal with the specifics of virtual conferencing. We constructed searches using the “NEAR” query term to eliminate articles which do not directly relate to virtual conferences (see Table S1 in the Supplement). This strategy was not entirely successful: for example, several papers were found concerning a “virtual geoscience conference” which was an in-person event whose subject matter was photogrammetry and other virtual techniques for collecting and presenting geoscience data (Chandler, 2016); these data were removed manually from the analysis. Nevertheless, the search yielded a total of 452 unique publications, which, when plotted by year (Fig. 1), show an increase in publications as of March 2020: a total of 312 articles within the search, almost 70 % of the total dataset, were published in 2020–2023. We additionally performed searches of the Directory of Open Access Journals (https://doaj.org/, last access: 29 August 2023), which allows less-detailed search queries to be constructed and does not allow article metadata to be easily downloaded. A search for the words “virtual” and “conference” in the title of articles produced 71 results, of which 63 (89 %) papers were published after March 2020, while a search for “online conference” yielded 56 results, of which 46 (82 %) papers were published after March 2020. Many articles published from 2020 onwards explicitly state that their rationale for considering virtual event organization was driven by the pandemic (e.g. Busse and Kleiber, 2020; Fulcher et al., 2020'; Gottlieb et al., 2020; Jain, 2022). In line with this change in interest, there has also been a shift in the type of literature published, with grey literature (blogs, social media, websites, etc) becoming an important body of work for several academic fields during the pandemic (Kousha et al., 2022).

Figure 1Plot of the Web of Science search results for articles with the words “virtual” or “online” and “conference” in their title, within two words of each other (total dataset = 452). An uptick in publications is visible from 2020 (312 were published from 2020 onwards), coincident with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic which precipitated a necessary rise in virtual conferencing.

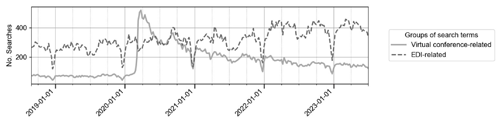

To assess the interest in virtual conferencing outside of an academic sphere, we analysed search data from Google Trends (https://trends.google.com/, last access: 29 August 2023), aggregating hits for searches for six terms related to virtual conferencing from the last 5 years (Fig. 2; see Supplement Table S2 for a list of all aggregated search terms). These data demonstrate an increase during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, with interest tailing off from the summer of 2020 to the present, albeit the interest remains higher than before the start of the pandemic.

Figure 2Plot of Google Trends data, across all search categories over the 5-year period from 2 September 2018 to 29 August 2023, for search terms related to virtual academic conferences and equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI). Co-located troughs in both search categories can be seen each December and correspond to winter breaks, with other dips aligning with holiday terms in many countries. Generally, interest in EDI gently increased with time, whereas that in virtual conferencing spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic but declined shortly after.

2.2 What motivations were given for increased “virtualization” of conferences at the time?

Conferences are efficient tools for facilitating academic discussion, career development, networking, and collaboration, but they present several inherent inaccessibility and inequality challenges. While traditional conferences have typically been held in person, the existence of virtual alternatives has long been recognized: the concept of virtual conferences and the use of virtual spaces to network were discussed in the literature as early as 1986 (Heim, 1986). Much of the earlier literature is primarily concerned with addressing technological developments in virtual conferencing, which facilitate increased opportunities for networking and professional development if an appropriate physical meeting is not feasible (e.g. Anderson, 1996; Blow, 2011; Thatcher, 2006).

As the virtual conference management and participation landscape developed further, articles began to identify communities for whom traditional, in-person conferences fail to cater and to suggest innovative virtual solutions to these specific hurdles. For example, Gichora et al. (2010) described a series of conferences run virtually via regional hubs across Africa, facilitating access to a conference without the need for the time and money required for travel. Black et al. (2020) outlined the benefits of virtual interactions over in-person conferences from a feminist perspective, drawing on the experiences of organizing a fully virtual, interdisciplinary conference (Lewis et al., 2019). Although the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic led to comparatively little questioning of the status quo, pre-pandemic literature identified numerous ethical and EDI issues with in-person conferences (Spinellis and Louridas, 2013; Fraser, 2017) and reported results and surveys of virtual conference participation (Gunawardena et al., 2001; Gichora, 2010; Erickson et al., 2011). It should further be noted that many smaller-scale conferences and seminars have been run virtually in previous decades without a published record of having occurred and would, therefore, have been missed here.

2.3 What challenges are associated with virtual conferences and how have these been addressed?

The appropriate use of time zones is a common issue faced by virtual meetings, with significant planning required to ensure that time zones are accessible to as many people as possible. Clear communication (e.g. time-zone-specific programmes) is vital to ensure full inclusion (Gichora et al., 2010; Niner et al., 2020; Gibson et al., 2021). Virtual events often use a range of technologies, with many of these rapidly changing or being replaced. Consequently, it is vital to provide extra time in the schedule to account for technical glitches and to give presenters time to practice; moreover, if events choose to facilitate live presentations, organizers should encourage pre-recordings as a backup in case of technical issues on the day (Gichora et al., 2010; Raby and Madden, 2021). Communication through other platforms (such as running social media campaigns or the use of mailing lists) prior to and during the event will also help ensure the smooth running of a meeting, as will having clear information in online form, such as a website (Gottlieb et al., 2020; Raby and Madden, 2021). The use of conference apps as the main communication platform may not be fully accessible, as they may not be compatible with all phones, tablets, or other devices, and this assumes that all participants have access to a device that can host apps (Niner and Wassermann, 2021). The use of apps may also present problems for digital accessibility needs (colour palettes, font, ease of reading, screen readers, etc.) which may not be considered in the design of such platforms (e.g. Kohler, 2023). Providing clear instructions on how to submit questions or how to attend any virtual activity or networking opportunity, with detailed explanations or access to help pages for any new technologies being implemented, is crucial to avoid inadvertent exclusion (Raby and Madden, 2021).

Many event reviews discuss the challenges in creating effective networking environments and fostering participant engagement during online meetings (e.g. Fulcher et al., 2020; Correia, 2021; Gibson et al., 2021; Raby and Madden, 2021). In particular, virtual poster sessions have often been difficult to design, with limited success in promoting engaging networking. While there were virtual poster sessions prior to COVID (e.g. the AGU Virtual Poster Showcase), feedback on the success of these events is limited; however, introducing the inclusion of other media (e.g. videos or QR codes) could enhance engagement (Raby and Madden, 2021). There may be multiple reasons why online engagement is hindered, with some people finding it more difficult to interpret social cues in virtual spaces, making communication more challenging, or with people experiencing or expecting to experience more hostile interactions online than in person (Niner and Wassermann, 2021). While more structured virtual activities have been used to make online networking more successful (Fulcher et al., 2020), other reports suggest using alternative ways to engage that allow flexibility (Raby and Madden, 2021). The use of engagement platforms will depend on the scale of the event, with break-out rooms often working well in small meetings to promote participant engagement (Gottlieb et al., 2020'), but including features such as networking pages could help participants engage more easily (Raby and Madden, 2021). Experimenting with different types of platforms and engagement methods will help in future event planning for specific events (Niner et al., 2020).

The financial barriers that in-person events may create for people, often enhanced by geography, are commonly discussed (e.g. Sarabipour, 2020; Raby and Madden, 2021; Rowe, 2019). Many international conferences are hosted in the Global North, creating additional barriers to participation, such as difficulty obtaining visas, leading to biased attendee demographics (Waruru, 2018). While there are still several challenges to overcome for virtual events (as discussed herein), fully online conferences often reduce financial and geographical barriers to attendance (Wu et al., 2022). Hybrid events may have additional costs for arranging a virtual component, as opposed to hosting the same event exclusively in person, depending on the type of event planned. However, including a virtual element to an event can lead to an increase in representation from traditionally underrepresented groups and foster new innovation and networking opportunities between new groups (Sarabipour, 2020). The potential accessibility of virtual events for low-income attendees is hindered if the conference fees are high, adding another barrier to inclusion (Niner et al., 2020; Raby and Madden, 2021).

2.4 Is EDI a focus of virtual conference design?

Our literature review shows that the shift to virtual events was not specifically motivated by EDI issues and that, to better cater to these issues, we should frame an appraisal of virtual conferences by their potential EDI benefits. This is borne out in the data analysed in Fig. 1. Of the 452 articles in the dataset, only 3 publications (<1 %) had titles that contained the strings “inclusiv” (contained in “inclusive” and “inclusivity”) or “accessib” (contained in “accessible” and “accessibility”). This quantitatively demonstrates that inclusivity and accessibility are not at the forefront of discussions around virtual conferencing, despite the increasing public interest in EDI issues, shown in Fig. 2. Several recent studies have highlighted the benefits to online conferences when EDI considerations are incorporated into conference design, including how virtual components can be used to create space and opportunities for minoritized groups by looking at audience engagement from a gendered point of view (Zhang et al., 2023). They demonstrated that, even though women composed an equal number of participants to men, they asked half as many questions as their male colleagues. A study of a different virtual conference from 2021 (de las Heras et al., 2023) provided an example of what can be achieved when the needs of minoritized groups, in this case women and early-career researchers, are kept in mind during the planning stages of a conference. By curating an event which centred the inclusion of these groups in the design of the conference (such as round-table events with quotas for the participation of these groups), the organizers received very positive feedback from the researchers involved.

Many people prefer in-person events for a variety of reasons, including technology fatigue during online events and better social cues when meeting in person. Thus, hybrid events seem to be a good way to incorporate the needs of a broad spectrum of people. However, the organization of hybrid events needs to carefully consider the needs of both in-person and virtual attendees in order to be inclusive.

Historically, EDI initiatives have not been the central theme of the published virtual conference literature, meaning that the implications of these types of events for EDI have often been overlooked. Many of these publications are reports of an individual virtual conference or series of conferences, written by the organizers of said conference, and therefore are not framed by an EDI agenda despite indirectly addressing many issues related to EDI (e.g. cost of travel and adhering to social distancing regulations). Reviews of virtual conferences are often (but not always) evaluated using feedback from participants, usually in the form of a post-event survey (e.g. Fulcher et al., 2020; Erickson et al., 2011; Busse and Kleiber, 2020; Moreira et al., 2022), and often (but not always) give practical advice for the future running of online conferences (e.g. Achakulvisut et al., 2021; Reshef et al., 2020; Gottlieb et al., 2020; Harabor and Vallati, 2020; Li et al., 2021; Fu and Mahony, 2023; Margetis et al., 2007). Specific advice given can apply to running an online conference smoothly without specific consideration of EDI (e.g. Pedaste and Kasemats, 2021; Seery and Flaharty, 2020; Reshef et al., 2020) or can be specifically tailored toward increasing EDI (e.g. Fraser et al., 2017; Gichora et al., 2010). While review articles cover a wide range of topics (e.g. survey feedback, online engagement, and communication), it is important to note that these reviews are not fully representative of everyone and may not capture all perspectives, especially if someone is not able to attend in the first place due to lack of accessibility. Similarly, having a virtual component does not automatically result in equitable inclusion (Niner et al., 2020). Virtual events may still present barriers to inclusion. These include socio-economic challenges, with the cost of internet access varying widely across countries (Raby and Madden, 2021). Additionally, not all people can engage with virtual events in the same way, with some attendees, including many neurodivergent or disabled participants, often facing additional focus and fatigue challenges (e.g. Nahass, 2022; Kukoyi, 2023), resulting in lower engagement and their inadvertent exclusion. As accessibility is not frequently a consideration in review articles of virtual events, there are several elements missing from the current literature. For example, live closed captions or subtitles for virtual and in-person events are rarely mentioned, as these may not have been considered far enough in advance for effective implementation (Gibson et al., 2021). However, these are crucial for the inclusion of those with certain disabilities and participants with different first languages to the conference (Seery and Flaharty, 2020; Wu et al., 2022). The benefits of effective subtitles and transcriptions in online environments are clear, with higher engagement from people with hearing and motion impairments in online lessons (Federico and Furini, 2012). In order to produce effective subtitles or closed captions, a clear audio connection is required (which may be restricted by poor microphones or acoustic environments) that may generate additional costs which should be considered early (Federico and Furini, 2012).

In-person academic conferences have existed since at least the 18th century (Bigg et al., 2023) but have often lacked meaningful consideration of EDI in their planning. In recent years, virtual conferences have increased in popularity, with the COVID-19 pandemic showing that increased use of virtual and online platforms leads to a huge increase in collective experiences, regardless of the limited experience of hosting virtual events many people had prior to the pandemic (Eventcube, 2023). As virtual and hybrid conferences continue to be utilized, it is vital that the academic community incorporates accessibility and inclusion into their planning. With this in mind, in the section below, we collate and combine recommendations from across both the literature and the authors' experiences running and participating in virtual/hybrid conferences and give concrete advice regarding the running of future events. As the breadth of the literature shows, each online conference will have different audiences, goals, and ways of planning (e.g. Gichora et al., 2010; Niner et al., 2020; Gibson et al., 2021; Raby and Madden, 2021). However, by utilizing diverse mechanisms for running conferences, novel and inclusive experiences can be had by all participants of a virtual or hybrid conference, both technologically and socially. As virtual conferences continue to take place, with hybrid events becoming more frequent, the ways of ensuring inclusion and accessibility will grow, with new ideas and technologies always emerging. Therefore, the following guidance should be taken as advice, rather than as rules.

3.1 Stage 1: pre-event planning and event design

3.1.1 Who?

Often, event planning begins when several people come together to discuss ideas, before the formation of an official planning committee. During these early discussions, several aspects should be thought about (e.g. target audience(s), title/theme, organizational roles, timelines, and communication strategies). Early decisions on the precise event theme and target audience are important for every other step, and they will be used as a foundation for communication and accessibility planning. During these early stages, ensuring diversity and inclusivity of those involved is crucial. Be proactive in inviting early-career colleagues and those from historically marginalized groups who might not otherwise become involved. Consider ways for marginalized groups to amplify their voices during the design stage of an event as well as compensation for any time given to volunteers (e.g. discounted registrations, society membership, or monetary compensation). It is important that volunteers are valued and not invited to tick a diversity box. Everyone's opinions and ideas need to be listened to and discussed. Furthermore, involving a broad range of people means that specific considerations for different marginalized groups are less likely to be overlooked. In the presence of a team of organizers from a diverse range of backgrounds who are treated equitably, organizers and attendees alike will likely feel more able to raise any foreseen issues before the event, thereby reducing the likelihood of negative experiences.

The following considerations are important at this stage of the planning process:

-

Target audience. Work out who the target audience(s) is for the event and how best to reach them. Different audiences may be more familiar with different platforms or have different needs or expectations of an event. Different approaches or structures of an event (or event series) may be required depending on the audience, as people engage in different ways (e.g. lecture-style, panels, open-dialogue discussions, and audience participation).

-

Presenters. If inviting/reviewing applications for speakers or other event roles, aim for a broad and diverse range of presenters to widen representation. Inclusion statements and codes of conduct can help, but many events still fail to provide a diverse line up, restricting the range of perspectives and worldviews available. If running an event with invited speakers, consider fee waivers for speakers at the event. This is particularly important for EDI-related events, where many speakers often carry out their work on a voluntary basis. Depending on the scope of the event, it can be a good idea to encourage people to talk about both their research and EDI-related concepts during the same presentation.

Avoiding tokenism and ensuring that the most appropriate people are selected for the event being organized is crucial. Tokenism, where someone is invited because of their gender, socio-economic status, ethnic background, or other characteristic to meet quotas, undermines equity movements and does more harm than good to EDI work, reducing the benefits of a truly diverse community in terms of diverse perspectives and ideas (Kamalnath, 2020). If it proves difficult to identify diverse experts or speakers, rather than assuming there are none, re-evaluate it from a different perspective and consider alternative ways (e.g. connecting with specialized groups) to reach people outside of the committee's network. This may require more pre-planning in order to find the best people for a topic or talk, but meaningful diversity and inclusion take time and effort from everyone.

When potential speakers for an event have been decided upon, make sure to communicate clearly with them at an early stage. The exact format, purpose, and length of a talk as well as any deadlines (e.g. for pre-recorded talks) should be shared as soon as is feasible. Similarly, if inviting a speaker, it can be a good idea to explain why you feel that they would be a good fit for the talk and to ask for suggestions for alternative/additional speakers to try and reach new networks. Share any accessibility information (see Sect. 3.1.6) and format requirements with speakers and panellists early in order to help them with the preparation of talks. If a panel discussion is planned, communicating any planned questions before the event can ensure that the event is more accessible to many people (Nocon, 2021). A pre-event session or “dress rehearsal” can give volunteers, invited speakers, or panellists the opportunity to familiarize themselves with the platform, ask any questions, and reduce uncertainty of how the event will run on the day (Nocon, 2021).

3.1.2 When?

During this stage, there are several decisions that need to be made to help streamline the rest of the event planning:

-

When should we run the event?

-

Is there a cycle for events like this?

-

What permissions need to be sought?

-

Can we tag onto a larger event which will increase our audience or should we do it alone?

Thus, the following considerations are important:

-

Time zones. Which time zones are your target audience and speakers located in? Will you need to rerun certain sessions to facilitate reaching a wider audience? If you are working across multiple time zones, what steps can be taken to ensure accessibility? Providing pre-recorded talks before the event can allow people to submit questions and become more involved, while providing a recording of the event afterwards can allow it to be shared with people who could not attend live. Furthermore, consider providing a platform for continued discussions after the event to allow participants unable to attend live to share their opinions and ideas.

-

Dates for the event. When choosing dates for the event, researching possible time clashes early is important to avoid any issues later. This should include identification of national holidays, religious and holy days or times, and any other events that may restrict attendance for some people. Avoid clashing with other conferences in similar or adjacent fields. The timing of an event may limit participation from particular groups and reduce the diversity of participants.

3.1.3 Budget

Online conferences do not have many of the associated costs of an in-person event, such as room hire, catering, and printing, but there are still likely to be some, particularly with respect to technical support and accessibility planning, as many free virtual platforms have limited capabilities (Barrows et al., 2021). Thoroughly research the various options to decide what mix of platforms and tools is most suitable for the event (see Sect. 2.6). If you do decide to charge attendance, try to minimize the fees and consider waivers for attendees from middle- and low-income countries. Be transparent to participants about where the money is being spent.

If running a hybrid event, the fees for those attending virtually should be considered carefully. Although many of the costs associated with in-person attendance do not apply to someone attending remotely, some costs remain, such as speaker expenses and running the online platform. The geoscience community has yet to identify an appropriate way to charge for virtual attendance at hybrid conferences. For example, the Mineralogical Society of the United Kingdom and Ireland typically charges virtual attendees fees that are 40 %–60 % of those for in-person attendance. Other conferences, such as the European Geosciences Union (EGU), have charged a slightly reduced registration fee for virtual attendees of their general assembly. However, many events, such as the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting 2023 (AGU, 2023), have charged registration rates for virtual attendance that are the same as in-person participation, without a clear explanation of why virtual costs were so high, thereby reducing accessibility to participants with limited funding.

Nevertheless, there is a concerning trend of events not considering a virtual component due to potential high costs or fear of the unknown. When asking event organizers why there is no virtual element to an in-person event, the authors have frequently been told that this would require a full audio visual (AV) set-up, which would be very costly and outside the budget of many smaller events. Alternatively, the authors have been told of dwindling attendance online as a reason for dropping virtual components, but this may be more linked to the lack of true engagement opportunities online or high costs for virtual attendance, as mentioned above. There are several simple steps that can be taken to include virtual components, including the use of microphones by in-person attendees for questions/talks (which are generally used at most in-person events as a norm) or sharing presentations through the virtual platform software rather than just pointing a camera at a screen. Several simple steps, which do not require significant funding, can be undertaken to create a more inclusive experience, including asking attendees in advance, acquiring sponsorship, or doing research into alternative ways to engage. Virtual components should not be dismissed before true consideration of how they can be included.

3.1.4 Technology and event format

Virtual events can offer much more flexibility than in-person events. Common virtual-event structures include a 1 h panel discussion/webinar or a more extensive series of short talks and discussions. With no need for the audience to travel to the location of the event, sessions need not be consecutive or run on subsequent days. Talks may also be made available on demand, allowing participants to pre-watch and share questions in advance to allow engagement beyond the live presentations. There are opportunities to combine multiple formats through virtual events, with a level of flexibility not previously available. The format used should be adjusted to reflect the specific goals of the event (dissemination of research results, audience, participation, feedback, networking, etc.). A good approach is to make fundamental decisions about structure (e.g. platform, talk availability through recordings/live presentations, poster session formats, and hybrid or fully virtual format) as far in advance as possible, announcing details early in a clear, accessible, and transparent way. Similarly, many people are not familiar or comfortable with some technologies and can get overwhelmed by new platforms and software as well as overly complex instructions, resulting in their exclusion from participation. Consider ways to overcome this, such as making instructions as clear as possible, including annotated screenshots to help guide participants, or offering support through correspondence with participants and speakers.

There are several types of platforms and technologies that can be used for online events, each of which have different features and capabilities. As well as standard video-conferencing platforms such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams, additional live-streaming services, such as YouTube, StreamYard, or Twitch, may be used to reach a wider audience. Ancillary services may be used alongside the main event platform in order to increase audience participation and inclusion (e.g. AhaSlides or Slideo) or to facilitate networking (e.g. Gather, previously Gather Town). Consider that many platforms or services may be unavailable in some countries; consequently, alternative methods of engagement may be needed to ensure full accessibility, depending on the target audience of the event (such as using additional live-streaming services and uploading recordings and transcriptions to alternative video-hosting platforms afterward). Similarly, different platforms have different accessibility features; consider whether it offers options for reliable captions and screen-reader compatibility when deciding where to host your event. When choosing a platform or technology for your event, ensure that they support the needs of your event. If possible, ask the providers of the platforms you are using or find information online for aspects such as streaming capabilities and limitations, design options of events, reporting metrics, plug-in options, customer support, and other accessibility features. Importantly, test the application of any platform prior running the event in order to ensure that it works in the way that you desire.

3.1.5 Promotion and communication strategy

The promotional strategy will depend on your target audience. Different target audiences mean different ways of communication need to be considered. How will you ensure that event information is shared with all target audiences? How will you reach audiences outside of your network and engage people who are not traditionally involved? If your event is open to everyone, consider how the promotional strategy will make it clear that all people are welcome. For communication with speakers and other participants, announce deadlines early and remind people when they are approaching.

Social media platforms can be a great tool for spreading the word about an event, along with disseminating a registration link. Consider using social media platforms like Facebook, LinkedIn, X, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, or any other platforms on which you may be able to engage with potential participants. However, other methods should not be forgotten, as many people do not engage with social media. Consider targeted email campaigns, printed posters for notice boards, and inclusion in newsletters and mailing lists. When utilizing these methods, consider the accessibility of the content being distributed. Ensure the use of alternative (alt) text for online content and accessible design in the generation of any graphics (Sect. 3.1.6; Chiarella et al., 2020; Jackson, 2020). A social media campaign may help gain momentum and get the most interaction with other stakeholder groups. Plan several posts before the event, such as a save the date, speaker introductions, description of themes, and registration links in the run up to the event to help increase engagement. Ensure adequate time to share the details, as it can take a while for details to be circulated. Accessibility of social media plans should be discussed in advance to avoid inadvertent exclusion. Working with other groups to share event details can also help to reach a wider audience. Similarly, these groups could be used to discuss ideas and gain feedback on plans.

A word of caution: even for free events, it is a good idea to require prior registration by the participants. Unfortunately, there have been instances in which meeting links were shared publicly on social media, resulting in so-called “Zoom bombing”, where individuals shared inappropriate content or otherwise disrupted the session. Prior registration minimizes the risk of such disruptions. Additionally, a designated person should be charged with handling such situations promptly by blocking and removing that individual.

3.1.6 Specific tips for accessibility and inclusion

The following are important factors that should be considered with respect to accessibility and inclusion:

-

Closed captions/subtitles. Closed captions or subtitles are critical to maximize engagement with any event for a variety of reasons. For example, people with hearing impairments and people whose first language is different from that of the conference may depend on these to fully engage with the material being presented (Cooke et al., 2022; Dello Stritto and Linder, 2017). Captions or subtitles may help people from all backgrounds to remain focused on the materials being presented; moreover, if attendees are in a noisy area (as not everyone has access to quiet working spaces) captions or subtitles can greatly aid with focus. It is important to highlight that closed captions (assumes audio cannot be heard, includes sound effects) and subtitles (dialogue transcriptions only, assumes other audio can be heard) offer different benefits; thus, for any event, the more relevant form should be selected (Rev, 2021).

Closed captions/subtitles can be deployed in a number of ways. Many virtual event platforms offer in-built auto-generation options, as do existing third-party artificial intelligence (AI) services, although there may be issues with accuracy if using auto-generated captions (Besner, 2019; Leduc, 2020). Other services, such as Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART, 2024), have received positive reviews; however, if going with auto-captioning, research on the accuracy and reliability of the service should be undertaken. Human transcription services are often more accurate than auto-generated options and, thus, are preferable, but they will typically cost more and may not be possible live. Research before the event is needed to see what options are available and which service is available in your region or meets your audience's needs. Legal requirements for closed captions during virtual events vary with geography and institution, so check those relevant to you before making any decisions. However, if the event is hybrid, it is crucial to ensure that in-person attendees use a microphone so that all attendees (including those in the virtual space) can clearly hear the comment/questions/talk. Online attendees also need to use good audio connections, although the traditional “shouting a question to the speaker” approach of many in-person events will exclude online attendees completely and, consequently, result in inaccurate captions and transcriptions.

-

Transcriptions. Transcripts can be helpful for keeping a record of discussions and debates that take place during an event, and they can consequently be used as a resource to write up conference papers or blogs to share outcomes after the event. These can be auto-generated by most video-conferencing platforms or provided by a third-party AI service. Check the quality of any transcripts before providing them to attendees, particularly if auto-generated by software. However, the use of third-party transcription services comes with a potential breach of privacy, as all captioning services require access to speakers' content and, depending on terms of service associated with individual services, may claim exclusive rights to processed user content. As well as a potential privacy violation for the individuals affected, this could be counter to institutional protocol on data protection and could potentially violate the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (Distelmeyer, 2023). Choice of an AI closed-captioning service should, therefore, consider data usage, and informed consent must be obtained from all speakers before a captioning service is used. Data protection is also something that should be considered with respect to the use of all online platforms, especially those that collect user information (e.g. emails), but more discussion on data protection needs to be had to fully understand the potential impact.

Before the event, a person should be assigned transcription reviewing, as this can be a time-consuming process. Also consider the availability and accessibility of these resources. Can anyone access them? Will they be shared in a follow-up email or linked with recordings? Do people need to contact the organizing committee for them? Whatever the decision, this needs to be communicated clearly to participants before and during the event.

-

Languages. Many people may be presenting and participating in their second or third language. Be patient and respectful of the fact that people may be more accustomed to a different language than that in which the event is held. Consider running parts of the event, including social events, in a language other than the main language, depending on the demographic of participants. Similarly, providing support for speakers that may not be presenting in their native language may help ensure that people are comfortable while presenting. These could include mentorship opportunities, practice runs, or feedback services, and they could significantly help people's confidence in taking part in an event. As with transcripts and closed captions, AI can offer the possibility of live translation, partially circumventing language barriers and improving accessibility, although this is still an emerging technology and has limitations. Sign language interpreters offer another way for people with hearing difficulties to engage with content. However, forms of sign languages vary globally, and consideration needs to be given to what is most relevant to your event; whether including sign language options would be appropriate; and, if not, what alternatives can be utilized to ensure accessible content.

-

Accessibility in presentations. Issue guidelines to participants about how to make slides accessible (AHEAD, 2023a, b). In particular, be mindful of colour schemes and typefaces which may cause legibility problems for participants with colour vision deficiency, dyslexia, or similar (Wickline, 2001; De Paor et al., 2016). There are several resources available to check accessibility (e.g. Colour Oracle and Coblis – Color Blindness Simulator). Further, the amount of text on a single slide, the colour of the text, and the contrast between text and background are all important considerations. Avoid placing important information at the bottom of the screen where it may be covered by subtitles/captions. Marks (2018) is one example of a comprehensive guide on how to make and deliver an accessible and inclusive presentation which could be shared in advance to help presentation planning; however, there are numerous options available to utilize.

-

Social media. If planning a social media campaign (as described in Sect. 2.1.6), the accessibility of posted content needs to be thought about in advance. Each platform offers different accessibility features that should be researched in advance. Ensure the use of alt text and that graphics are designed in an accessible way (e.g. fonts and colour schemes) if using graphics. There are many other considerations, such as avoiding the overuse of emojis or ensuring the use of capital letters in hashtags (i.e. camel case) to help screen readers engage more meaningfully with content. Consider assigning dedicated people to research social media accessibility to ensure that your content is accessible to everyone.

-

Other considerations. The inclusion of breaks during an event to allow rest is a crucial step to allow people to recover from screen time and prevent overstimulation. For online conferences, this could take the form of ensuring that a conference's schedule is well staggered to allow breaks and rest periods. For in-person elements of hybrid events, follow best practice for in-person events (e.g. separate spaces for different needs). There are several extensive reviews of in-person accessibility needs that can be explored, including, EOWG (2022), Council of Ontario Universities (2016), and Felappi et al. (2017), although these are not the focus of this paper.

3.1.7 Presentation format

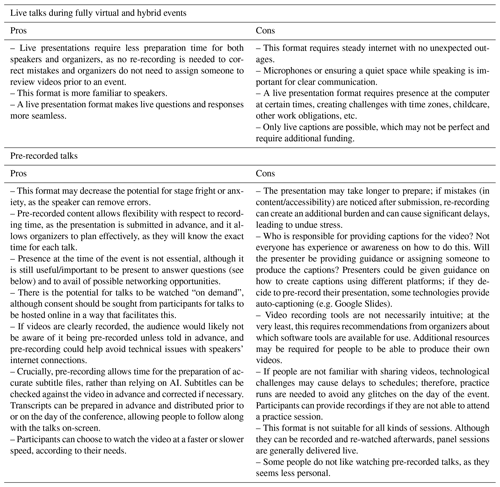

Virtual events offer a unique opportunity to have various styles of presentation. Talks within a conference session (or similar) may be live (given on the day), pre-recorded (recorded in advance, with the recording shared during the event), or a combination of the two. There are many benefits to both styles, but pre-recorded talks allow for more accessibility options, and they will ensure that exact timings are maintained during the event. This is particularly useful if running a larger-scale conference with multiple short talks or with multiple parallel sessions. However, care should be given to what your choice means in terms of accessibility, as screen readers may not be able to engage with presentations shared through a pre-recorded video (Vasquez, 2021); therefore, the presentation recording should be made available beforehand to allow people to engage more meaningfully. There are several pros and cons to both formats, with some summarized in Table 1. There is room for a combination of these two approaches: for example, pre-recorded talks could be made available as a backup in case of internet connection issues or could be live-streamed as if given live but with pre-prepared subtitle files. A willingness to be flexible in your approach to accommodate the different needs of your presenters and attendees will go a long way, although it is also important to be mindful of going too far the other way and creating too much of a logistical burden for the event organizers.

3.1.8 Other considerations for the pre-event organization stage

The following are other important considerations at the pre-event stage:

-

Code of conduct, etc. An equity, diversity, and accessibility statement should be prepared and shared in advance of the event through promotional materials, social media postings, website pages, and any other platforms available. This should be shared again during the event introduction. Take time before the event to come up with a code of conduct and other housekeeping information and provide this document to both speakers and attendees before the event. A code of conduct should include a list of what is/is not permitted as well as any consequences there may be for those who choose not to abide by it. Consider having a way for people to signify they need assistance from a member of the conference team, such as using a specific emoji reaction included in most video-conferencing software. Give clear guidance on how violations will be reported and dealt with (e.g. email, private chat function, or removal of participants). Consider where participants will go for assistance during both fully virtual and hybrid events in advance to ensure that help is given in an effective manner.

-

Planning document. Before the event, create a central document or other record with all details that may be needed on the day. This can act as a central database for all relevant information and help address any challenges that arise during the event. This should contain any prepared statements (e.g. the code of conduct, the question and answer process, information on recordings if available, and the follow-up statement) along with logistical information (e.g. the speaker lists and contact details, access links, and announcements). All volunteers should have access to this resource before the event. A similar document should be designed for presenters to give all relevant information, links, pre-planned questions, and other logistics to help ensure smooth running on the day.

-

Pre-event accessibility questionnaire. To help ensure that the needs of participants are met for your event, a pre-event questionnaire should be thought about and distributed to gain insights into the accessibility needs of your participants. This form could be linked with registration, depending on the platform being used (e.g. Eventbrite) or circulated through social media/email lists. This will greatly help planning and ensure that people's needs are met for full inclusion during the event.

-

Networking features. Consider innovative networking features as a way to help foster new engagement during online events. This is particularly important for hybrid events that may not have large online engagement from in-person attendees who fear missing out on other opportunities. Restrictive networking opportunities may reduce online engagement, so consider what your platforms offer to increase connectivity (e.g. group chats, roundtables, or matchmaking). Consider gamifying online elements to promote wider engagement and networking.

3.2 Stage 2: during the event

Much of the work for the actual running of the event will have been done in Stage 1, and this is why it is such a crucial step in (virtual) event planning. This section discusses how some of the more specific features may run on the day, with accessibility in mind, and includes elements that should be defined in the pre-event stage.

Some of these aforementioned elements are as follows:

-

Volunteers and staff. What volunteers or staff are needed during the event? While many events will need volunteers and staff to host sessions or run discussions, there are many other roles that should be considered beforehand to ensure the smooth running of an event, including technical support. All volunteers and staff should be confirmed before the event, expectations should be clearly outlined, and everyone should know what their role is. A plan for communication, to deal with daily communication and any issues that arise (e.g. messaging platform or emails), during the event should be considered.

-

Questions from the audience. Make sure the audience has the option to ask questions, either verbally or in text (e.g. through a chat box function), and clearly explain how questions can be asked at the start of the event to ensure full inclusion. Many platforms offer a “raised hand” feature that can be used to avoid disruption to a presenter if audience members have the option of asking a question in real time. If the event is also being streamed to another platform (e.g. YouTube), ensure that someone is responsible for monitoring for questions on the second platform to allow all audiences to engage. Consider not recording the questions and answers section to lower the hurdle of asking a question. During both online and hybrid events (particularly during the in-person part of a hybrid event), make sure all people asking questions use a microphone, as some assistive technologies are dependent on their use.

-

Introductions. When introducing and talking to people, use gender-neutral language; do not assume pronouns; and, if possible, ask people their pronouns before the event. This can form part of the introduction package that should be developed before the event (Sect. 2.1.9). If a mistake happens, there are a lot of resources that can help to learn the correct way to respond (e.g. Pronouns.org, 2023). Avoid binary turns of phrase, like “Ladies and Gentlemen”, or gendered terms, such as “Welcome Guys!”, which may inadvertently exclude people with non-binary gender identities. Encourage people to include their pronouns in their online tag. However, there are many reasons why people might not want to publicly declare their pronouns, so this should always be optional. When speakers introduce themselves, it can be helpful for people with visual impairments for them to give a short visual description (e.g. I have brown shoulder-length hair and today I am wearing a stripy white and yellow jumper); however, do not force this, as not everyone will be comfortable with carrying out self-descriptions (see IDEA Inclusive AD Forum, 2021, for other examples).

-

Camera etiquette. Do not insist that cameras be switched on, as this may not be possible for every attendee, and people may request not to be on camera. Streaming attendees' videos can be problematic for people with a poor internet connection. Video fatigue (Bailenson, 2021) is also a reality, and if an event is going on for several hours, people need a break from being watched. Request participants not have moving backgrounds, as these use excessive bandwidth and may be distracting for other participants.

-

Event etiquette. Remind people of the code of conduct at the start of every session, including how/to whom to raise any concerns. If parts of the session are being recorded, let the audience know this at the start of the session.

-

Data and analytics. If the chosen platforms allow access to data and analytical tools to measure online engagement, make sure to avail of them during the event and use them during post-conference review.

-

Social media activity. Using social media during an event, to share discussions, ideas, and outcomes, can be a great way to encourage participation from a wider audience. Permission should be obtained for sharing anyone's research or image, and content should be shared with accessibility in mind (e.g. alt text).

3.3 Stage 3: after the event

Any activities for the post-conference phase (e.g. follow-up emails) should be planned in advance, as people often need to take time away after event planning and there may be limited volunteer and staff help for carrying out any after-the-event plans. There are several aspects that should be considered, with some examples listed below:

-

Recordings and transcripts. If providing recordings, ensure that full, accurate transcripts are available and that any subtitles/captions uploaded are correct. Reviewing captions and transcripts can be a time-consuming process, so ensure that sufficient time and volunteers are available for this. Decide in advance how soon after the conference you expect these to be available, communicate this to participants, and keep to this deadline.

-

Follow-up email. Whilst this is optional, it can be helpful to direct attendees (or those who registered but could not attend) to any available recordings, relevant links, and information, and this should be planned in advance. This also provides an opportunity for people to give feedback, if requested, through questionnaires or polls (see below). Make sure to provide a way for participants to share their experiences and thoughts, which can be used to build on for future events.

-

Feedback. Measuring feedback can be difficult, but a short questionnaire (or equivalent) could be included in the follow-up email. This will require additional support to review and analyse the feedback, but it can be a great way to learn how to improve accessibility for future events, which will be particularly useful if running an event for the first time. Consider asking for feedback related to session engagement, diversity, technology experiences, and overall attendee enjoyment and accessibility. However, be mindful of overwhelming the audience with surveys. There are different ways to collect feedback (e.g. polls on virtual platforms, interactive presentations, and message boards), so consider what works best for your event and research what other events have done to maximize feedback collection. Additionally, feedback should be something people have the opportunity to provide throughout an event, not just afterward. Consider using QR codes and posting links regularly for attendees to access feedback forms.

-

Communication channels. How can people get in touch with you/the organizing team post-event? If using an email, someone will need to monitor this and answer any questions. Some events may also have corresponding Slack/Discord/other platform channels to help participants network and discuss more between themselves. If this is something to be launched for the event, it will need consideration at an early stage to ensure engagement and accessibility. Also consider how long after the event this will continue to be live, and communicate this to participants early.

-

Certificate of attendance. Some participants may be required by their workplaces or university to produce a certificate of attendance for the event. Appoint a volunteer to respond to such requests.

The global COVID-19 pandemic caused a drastic shift in the way people communicate with each other. Many people were forced into working from home due to lockdowns, causing working groups and research teams to utilize video-conferencing technologies far more frequently to ensure continued collaboration and connectivity. The restrictions on travel, both locally and internationally, also had a drastic impact on geoscience events. As the pandemic progressed, many planned in-person events began to be redesigned for a virtual platform, with novel and innovative ways created for participants to communicate and network with each other. This virtual network has led to many new collaborations between people who may have never met in person, and it has also helped to strengthen relationships already in place, allowing for a more diverse, interconnected, and effective research community across the world.

However, this move to a virtual landscape was sudden; consequently, consideration has not always been given to the accessibility of these virtual platforms and events. Whilst we are currently seeing a resurgence in the number of purely in-person events, the use of virtual and hybrid platforms is likely to continue, with many virtually based groups now in existence, and flexible and remote working options having been established. The move to a virtual and hybrid landscape also highlighted the geographical and socio-economic disparities of in-person event accessibility, with the financial and logistical burden of travel to events being felt by some researchers more than others. This has led to inequalities of opportunity and to biased attendances at international in-person conferences, which do not represent the entire spectrum of researchers. Consequently, moving back to purely in-person events would dismiss the lessons learnt in event accessibility over the past several years and lead to the renewed exclusion of many people.

In order to avoid future exclusion, future virtual elements should not be dismissed in cases where prior virtual components of an event have not been successful (Niner and Wassermann, 2021). Reflection on why an event (or a component of one) was not successful, asking for feedback where possible, and learning from other examples is suggested to create recommendations for how to try and make future events more inclusive and engaging. It is important to discuss and plan accessibility and inclusion early in event planning to ensure a safe and engaging environment for all potential participants (Gibson et al., 2021). Virtual conferences will only become truly accessible and inclusive if the entire community actively works towards it (Niner et al., 2020), with active consideration and discussion of best practices for different people. This includes consideration of which communities are best served by best-practice guidelines as well as the continual re-examination of procedure as technology and expertise develop new methodologies for increasing the success of conferences for everyone. As new ways of interacting with each other continue to be established, we need to remember the lessons learnt from the initial move to virtual events. If thought and consideration are not put into the virtual part of future online and hybrid events, then these will not be effective and may exclude most participants.

In summary, there are some key considerations identified that can help with event planning to act as a starting place for planning an inclusive and accessible virtual event:

-

Accessibility needs to be part of the planning phase, not an afterthought.

-

Decide early on the dates, length, purpose, and title of the event, and communicate this information early and clearly.

-

Ensure diversity of the planning committee and speakers to ensure that different ideas and viewpoints are considered. Different perspectives are needed from the people that will be most impacted by the choices being made (e.g. Kingsbury et al., 2020).

-

Ask participants about their virtual access needs before the event and then ensure that these needs are met throughout the event. Consider providing a way for people to communicate real-time needs during the event and have a plan in place to address any challenges that arise.

-

Clearly outline the planning/time commitment involved for volunteers/organizers and decide on roles (and associated responsibilities) before the event, so everyone knows what they are doing and when they are needed (feeds into communication). Ensure sufficient volunteers/staff for the event being organized. It can be quite overwhelming to try to do multiple things (e.g. monitor the chat and feed panel questions).

-

Evaluation of the event can be achieved through a short survey (prepare this during the pre-planning phase) sent to participants shortly after the event. Asking about location, career stage, etc. can help monitor and evaluate where your network reaches and help in future event planning.

-

Accessible and open communication is key! Ensure opportunities for people to provide and receive information on all aspects of the event.

While there are doubtless many other considerations around virtual accessibility not covered here, we hope that this article can provide a checklist for those who wish to curate more inclusive and accessible virtual events going forward. In addition, we have compiled an initial checklist to use as a starting point for planning (see the Supplement).

No underlying software code was used for the literature review. For access to the available articles and literature used in Fig. 1, please see the list of specific search terms in Tables S1 and S2, with links to available search results included in Table S1 in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-7-227-2024-supplement.

ALD, VD, and BW contributed equally to the formation of the article, including the initial draft development. KM, RAW, AA, IC, CC, DH, MD, and LK all contributed to writing, reviewing, and editing the drafts of the manuscript as well as adding their experiences and ideas, leading to the submitted version.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests

This article was produced during volunteered time by the authors and was not funded by any external group or award. As no humans or animals were included in this work and no personal information has been shared, no ethical review was required.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their comprehensive feedback and suggestions. We are also grateful to Martin Griffin, for his insightful and detailed feedback, and those who engaged with us at the EGU 2024 conference, where we presented these ideas. Additionally, the editor, Steven Rogers, is thanked for guidance and feedback throughout the submission journey. While we still have more to learn, these different perspectives and ideas were invaluable to finalizing this article. This publication emanates from a collaboration between the UK Polar Network; the Accessibility in Polar Research; the Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Geoscience (EDIG) project (2022); and the Mineralogical Society of the United Kingdom and Ireland. The authors acknowledge all of the stakeholders who have contributed to the findings and discussions shared in this article. In particular, we would like to thank the Birmingham Geo-Equality group for conversations during the initial stages of this article. The EDIG project is made up of several volunteers from around the world who have helped us all to design, organize, and run several events, along with sharing their experiences and knowledge with the wider team – thank you to all of our volunteers (past and present) for all your time and effort in running the project. The EDIG project would also like to thank all of the supporting institutes, organizations, and other geoscience initiatives that have helped EDIG plan and host events, along with sharing their knowledge and experience to help our own learning journey. The EDIG 2022 Conference was financially supported by the Institute of Geologists of Ireland (IGI) and iCRAG, the SFI Research Centre for Applied Geosciences. The Polar Early Career Conference 2021 (discussions from which resulted in this paper) was organized by the UK Polar Network and the UK NERC Arctic Office. The authors also with to thank all of the individuals who have encouraged and helped us to learn outside of our initiatives and groups – we are grateful that you took the time to share your knowledge and experiences with us.

This paper was edited by Steven Rogers and reviewed by Christopher Atchison and one anonymous referee.

Abeyta, A., Fernandes, A., Mahon, R., and Swanson, T.: The True Cost of Field Education is a Barrier to Diversifying Geosciences, Earth ArXiv [preprint], https://doi.org/10.31223/X5BG70, 2021.

Achakulvisut, T., Ruangrong, T., Mineault, P., Vogels, T. P., Peters, M. A. K., Poirazi, P., Rozell, C., Wyble, B., Goodman, D. F. M., and Kording, K. P.: Towards Democratizing and Automating Online Conferences: Lessons from the Neuromatch Conferences, Trends Cogn. Sci., 25, 265–268, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.01.007, 2021.

AGU: AGU Register & Attend webpage for the AGU23, https://www.agu.org/fall-meeting/pages/attend/register, last access: 1 December 2023.

AHEAD: Creating Inclusive Environments in Education and Employment for People with Disabilities: Accessible PowerPoint Presentations, https://ahead.ie/wam-remoteworking-resources-powerpoint, last access: 17 February 2023a.

AHEAD: Creating Inclusive Environments in Education and Employment for People with Disabilities: PowerPoint Presentation Accessibility Guidelines, https://www.ahead.ie/allyship-accessible-comms-presentation, last access: 17 February 2023b.

Allen, M.: Virtual conferences are more inclusive and greener, Phys. World, 35, 11i, https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-7058/35/02/14, 2022.

Amarante, F. B. D. and Haag, M. B.: Earth Science for all? The economic barrier to Geoscience conferences, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-1653, 2024.

Anderson, T.: The Virtual Conference: Extending Professional Education in Cyberspace, International Journal of Educational Telecommunications, 2, 121–135, 1996.

Bailenson, J. N.: Nonverbal Overload: A Theoretical Argument for the Causes of Zoom Fatigue, Technology, Mind, and Behavior, Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 2, https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000030, 2021.

Barrows, A. S., Sukhai, M. A., and Coe, I. R.: So, you want to host an inclusive and accessible conference?, FACETS, 6, 131–138, https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2020-0017, 2021.

Beilock, S.: How Diverse Teams Produce Better Outcomes, online blog, https://www.forbes.com/sites/sianbeilock/2019/04/04/how-diversity-leads-to-better-outcomes/ (last access: 15 September 2024), 2019.

Besner, L.: When Is a Caption Close Enough?, The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2019/08/youtube-captions/595831/ (last access: 10 August 2022), 2019.

Bigg, C., Reinisch, J., Somsen, G., and Widmalm, S: The art of gathering: histories of international scientific conferences, Brit. J. Hist. Sci., 56, 423–433, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007087423000638, 2023.

Black, A. L., Crimmins, G., Dwyer, R., and Lister, V.: Engendering belonging: thoughtful gatherings with/in online and virtual spaces, Gender Educ., 32, 115–129, https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2019.1680808, 2020.

Blow, N. S.: Making the conference scene virtual, Biotechniques, 50, 203, https://doi.org/10.2144/000113642, 2011.

Busse, B. and Kleiber, I.: Realizing an online conference: Organization, management, tools, communication, and co-creation, Int. J. Corpus Linguis., 25, 322–346, https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.00028.bus, 2020.

CART: Communication Access Realtime Translation, National Association of the Deaf, https://www.nad.org/resources/technology/captioning-for-access/communication-access-realtime-translation/, last access: 20 June 2024.

Chandler, J.: VGC 2016: Second Virtual Geoscience Conference, Photogramm. Rec., 21, 469–470, 2016.

Chatterjee, D.: How international conferences fail scholars from the global South: International Affairs Blog, https://medium.com/international-affairs-blog/how-international-conferences-fail-scholars-from-the-global-south-fbde14e5d1f1 (last access: 31 August 2023), 2022.

Chautard, A.: Inclusive conferences? We can and must do better – here's how, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2019/06/06/inclusive-conferences-we-can-and-must-do-better-heres-how/#:~:text=Many minorities also experience challenges,diversity should span beyond panels (last access: 1 November 2023), 2019.

Chiarella, D., Yarbrough, J., and Jackson, C. A. L. Using alt text to make science Twitter more accessible for people with visual impairments, Nat. Commun., 11, 5803,https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19640-w, 2020.

Cooke, M., Child, C. R., Sibert, E. C., von Hagke, C., and Zihms, S. G.: Caption This! Best Practices for Live Captioning Presentations, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO150246, 2022.

Correia, S.: Disadvantages of Online Events, https://blog.digitalnexa.com/disadvantages-of-online-events (last access: 31 August 2023), 2021.

Council of Ontario Universities: A Planning Guide for Accessible Conferences, How to organize and inclusive and accessible event, Online guide, ISBN: 0-88799-489-X, https://www.accessiblecampus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/A-Planning-Guide-for-Accessible-Conferences.pdf, 2016.

de las Heras, A., Gómez-Varela, A. I., Tomás, M.-B., Perez-Herrera, R. A., Alberto Sánchez, L., Gallazzi, F., Santamaría Fernández, B., Garcia-Lechuga, M., Vinas-Pena, M., Delgado-Pinar, M., and González-Fernández, V.: Innovative Approaches for Organizing an Inclusive Optics and Photonics Conference in Virtual Format, Optics, 4, 156–170, https://doi.org/10.3390/opt4010012, 2023.

Dello Stritto, M. E. and Linder, K.: A Rising Tide: How Closed Captions Can Benefit All Students, https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/8/a-rising-tide-how-closed-captions-can-benefit-all-students (last access: 10 August 2022), 2017.

De Paor, D., Karabinos, P., Dickens, G., Atchison, C.: Color Vision Deficiency and the Geosciences, GSA Today, 27, 42–43, https://doi.org/10.1130/GSATG322GW.1, 2016.

Distelmeyer, J.: Video conferencing as programmatic relations: conditions, consequences and mediality of Zoom & co., in: Video Conferencing: Infrastructures, Practices, Aesthetics, edited by: Volmar, A., Moskatova, O. and Distelmeyer, J., 1st edn., transcript Verlag (Digitale Gesellschaft), Bielefeld, Germany, https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839462287, 2023.

Dowey, N., Barclay, J., Fernando, B., Giles, S., Houghton, J., Jackson, C., Khatwa, A., Lawrence, A., Mills, K., Newton, A., Rogers, S., and Williams, R.: A UK perspective on tackling the geoscience racial diversity crisis in the Global North, Nat. Geosci., 14, 256–259, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00737-w, 2021.