the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The future of conferences: lessons from Europe's largest online geoscience conference

Hazel Gibson

Sam Illingworth

Susanne Buiter

In the early months of 2020, as the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) swept across the globe, millions of people were required to make drastic changes to their lives to help contain the impact of the virus. Among those changes, scientific conferences of every type and size were forced to cancel or postpone in order to protect public health. Included in these was the European Geosciences Union (EGU) 2020 General Assembly, an annual conference for Earth, planetary, and space scientists, scheduled to be held in Vienna, Austria, in May 2020. After a 6-week period of changing the format to an online alternative, attendees of the newly designed EGU20: Sharing Geoscience Online took part in the first geoscience conference of its size to go fully online. This paper explores the feedback provided by participants following this experimental conference and identifies four key themes that emerged from an analysis of the following questions: what did attendees miss from a regular meeting, and to what extent did going online impact the event itself, both in terms of challenges and opportunities? The themes identified are “connecting”, “engagement”, “environment”, and “accessibility”. These themes include concepts relating to discussions of the value of informal connections and spontaneous scientific discovery during conferences, the necessity of considering the environmental cost of in-person meetings, and the opportunities for widening participation in science by investing in accessibility. The responses in these themes cover the spectrum of experiences of participants, from positive to negative, and raise important questions about what conference providers of the future will need to do to meet the needs of the scientific community in the years following this coronavirus outbreak.

- Article

(562 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

1.1 The General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union

The European Geosciences Union (EGU) is Europe's leading organisation for Earth, planetary, and space science researchers. Based in Germany, the union had a global membership of 18 818 individuals in spring 2020, based in more than 135 countries. Every year, in approximately April or May, the EGU holds its annual General Assembly in Vienna, Austria. It is the biggest geoscience conference in Europe. As a significant part of many Earth, planetary, and space scientists' research calendars, the EGU General Assembly is a showcase for research from across 22 scientific divisions. The divisions include fields like biogeochemistry, ocean science, atmospheric science, and solar–terrestrial science, as well as more traditional geoscience fields like geodesy, geomorphology, Earth magnetism and rock physics, and natural hazards (among many others). In addition to the scientific research presented, the EGU's General Assembly provides researchers with networking and career development opportunities, training, and the ability to connect with their extended global community – both personally and professionally. This is especially key for the early career scientists (fundamentally, researchers who are within 7 years of their most recent degree), who, in 2020, made up 56 % of the EGU's membership.

At the start of 2020, the EGU's organisational teams were 7 months into the build-up of the 2020 General Assembly, which was, that year, planned to be held from 3–7 May. Apart from the primary aim of enabling scientists to present their research and learn of the work of their colleagues, the focus of the 2020 General Assembly as an event hoped to highlight inclusivity, accessibility, and environmental sustainability, as in-person conferences are more and more frequently challenged to improve in these areas (Desiere, 2016; Hamant et al., 2019; De Picker, 2020; Foramitti et al., 2021). Inclusivity measures aimed to provide a safe and respectful environment for all, including the promotion of gender-neutral language, a dedicated person of trust on-site, free childcare, family and breastfeeding rooms, and a kid's corner. Accessibility measures included dedicated information for coming to and navigating within the conference centre, wheelchair accessibility, quiet rooms, catering options, information on visual accessibility, pilots with audio streaming and automatic captioning, and tips for accessible presenting. Measures aimed at reducing the environmental impact of the General Assembly centred on environmentally responsible catering sources, offsetting the CO2 emissions resulting from the travel of all conference participants to and from Vienna (in 2018 and 2019, voluntary carbon offsetting through the EGU was used by 25 % to 32 % of attendees), advising participants to travel by train to Vienna when possible (and promoting discounts offered by train companies to participants) and encouraging participants to use public transportation once in Vienna, by giving away a weekly transportation pass with every week ticket to the conference. Discussions in 2019 and early 2020 involved the consideration of enabling remote participation in a manner that would allow both remote and on-site participants to directly engage in questions and discussions, but this was not yet foreseen for the 2020 conference.

The annual call for abstracts closed in the second week of January 2020, with a new record of 18 036 abstracts submitted to 701 scientific sessions, compared to the 2019 General Assembly, which had 16 273 participating scientists, who presented 16 250 poster, oral, and PICO (presenting interactive content) presentations in 683 scientific sessions.

By the end of February, the rapidly escalating COVID-19 pandemic was the subject of constant discussion within EGU's governing council, who began planning several contingency strategies. By 19 March it was clear that the conference could not progress as planned, and for the safety of all members, it was announced that the in-person meeting would be cancelled and replaced with an online alternative. However, with less than 6 weeks until the start date of the conference, it was also obvious that this could not possibly be a conference like any previous EGU General Assembly.

1.2 The 2020 General Assembly: Sharing Geoscience Online

In designing EGU2020: Sharing Geoscience Online (hereafter EGU20) in the short time available, the organisers focussed on providing possibilities that could work across time zones for all authors to present their work and similarly for participants to access the presentations. To reinforce the EGU's mandate that all presentation formats are of equal value, previously assigned poster, oral, or PICO (an interactive presentation form delivered via touch screens) presentations were turned into a new concept of “displays”. The decision was made for two forms of scientific engagement to be possible for each display: pre-uploaded presentation materials that could be commented on and that were linked to the abstract and live text chat sessions that occurred during the originally scheduled presentation times from the programme published on 9 March 2020 (prior to cancellation). The pre-uploaded content with comments used the EGU's newly launched preprint repository, EGUsphere, which provided 50 MB of storage for each presenter to upload their presentation using one of four formats (mp4, jpg, pdf, or ppt). Authors were free to choose what to post alongside their abstract, e.g. an animation, a map, a poster, slides, a pre-recorded talk, a brief report, and so on. The uploaded materials were linked to the abstract, which had a DOI, and the materials were published via an open-access platform (in accordance with the EGU's publications policy, specifically a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License), unless authors chose a different copyright statement. The uploads were then made available for comment from the moment they were uploaded until 31 May 2020. The comments and materials remain accessible on the EGU website (https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/egu2020/sessionprogramme, last access: 18 August 2021) and EGUsphere (https://www.egusphere.net/conferences/EGU2020/index.html, last access: 18 August 2021).

The live text chat function was chosen as a compromise between accessibility, participant interaction, technical plausibility, and technical stability, with the theory being that the text would allow participation by participants who are deaf or hard of hearing (as there was no time anymore for testing stable solutions for video sub-captioning), encourage questions by all participants, and support engagement by people who had lower bandwidth or who relied on accessible digital technologies, approved by their organisations, to participate. Using the host platform Sendbird, each of the 701 scientific sessions was given a text chat channel that was linked to the pre-uploaded materials of that session, and that text chat was moderated by the session conveners (as would be the case for an in-person General Assembly). Text chats were open for the duration of the scheduled sessions, and any participant in the session (speaker, convener, or audience member) could contribute to the text chats to ask questions, comment on the work, or discuss ideas with other attendees of the session.

There was no limit to the number of people who could digitally attend the live text chats, and this number varied wildly. Though there was a median of 92 participants per chat, the largest chat had 796 participants. This made for very different experiences in the text chat sessions, as the chat window would normally scroll at the speed of the number of people submitting questions or answers. Participants could also follow multiple chats in different windows. The EGU made instructional videos with tips for both conveners and participants that had received over 23 000 views by the start of the conference. For example, one of the presenter tips was to prepare a one or two sentences summary of the display in advance, and this tip was widely followed.

In addition, some limited online provision had been made for networking and community building, and there were several live-streamed or pre-recorded video sessions – notably the EGU's flagship keynote union-wide events (the Great Debates and Union Symposia) and selected short courses. The EGU20 brought the annual photo competition online, encouraged science and art exchanges through the #shareEGUart programme and virtual artists in residence, ran a data help desk, enabled each of the 22 subject-specific divisions to hold their annual meetings, and even had an online closing party. The short time that was available to bring the conference online, however, also meant that other events and activities could not be scheduled. These included the special lectures from the 51 medal and award winners, most of the short courses, most of the networking events, the EGU mentoring programme, live-captioning of the keynote union-wide events, and measures to help visually impaired scientists (most of whom would not have been able to participate in the chats). As this was nothing like the experience that would normally be provided to members and was very much viewed as a pilot project, EGU's governing council decided to make attendance free, though only abstracts that had been submitted by the January deadline were eligible to be presented.

EGU20 launched on 4 May 2020 for a week of activities that saw over 22 300 individual users in 721 live text chats who posted approximately 200 400 messages. In total, 11 380 presentation materials were uploaded with the abstracts, which received 6297 comments by end of the week.

1.3 Conference feedback survey

Each year during and after the General Assembly, the EGU conducts an online survey among the participants to ask for feedback about the conference experience. The questions consider, among other things, the scientific programme, the role of participants in the conference, and the additional conference activities, such as annual meetings of the scientific divisions, the mentoring programme, or the photo competition. The survey forms an important source of information and feedback for planning the General Assembly the following year and has helped to drive positive change. For example, environmental sustainability and accessibility efforts were prioritised in planning new meetings after such comments were made via these surveys. However, the usual survey, which assumes, among other things, travel and on-site attendance, was not suitable for Sharing Geoscience Online, as it featured questions on travel to Vienna and on-site events, whereas online aspects were not included.

In order to take advantage of the unique opportunity EGU20 provided, and to try and gain some insight into where the potential benefits and challenges of an online conference of this size may lie, the authors decided to write an entirely new conference feedback survey. Given the massive upheaval in 2020, it was decided to shorten the usual General Assembly survey and focus it much more closely on the participants' experience of this pilot event. The survey was distributed to all attendees via email and through social media. There were 1580 complete responses (7 % of attendees), which is equivalent to the 2019 response numbers (n=1666 or 10 % of attendees). Of those complete answers there was a reasonable gender balance (46 % female, 51 % male, 0.8 % non-binary/other, and 3.2 % prefer not to say), and 56 % identified as early career scientists. Of the completed surveys, 91.5 % said they had never attended a virtual conference before.

The methodology that was adopted in this study involved surveying participants of EGU20 and asking them for their feedback with regards to their experiences of the online conference. Qualitative content analysis (see, e.g., Erlingsson and Brysiewicz, 2017) was then used to interpret the responses to this survey. The questions that were used in this survey can be found in Appendix A. The study was carried out according to the British Educational Research Association's (BERA) ethical guidelines for educational research, and given that the data contain responses that could lead to the identification of the respondents (even with their name and institute redacted), we have chosen not to make the survey responses available, but a redacted version can be provided upon request.

Any approach which utilises a qualitative content analysis should be guided by the following six steps: formulation of research question, selection of samples to be analysed, definition of categories to be analysed, outline and implementation of coding process, trustworthiness of coding, and analysis of the results of the coding process (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005; Illingworth, 2020). In defining the methodology utilised in this study, we will outline the first five of these steps here, with the sixth (i.e. the analysis) being presented in Sect. 3.

2.1 Formulation of research questions

The purpose of this study was to better understand how participants of EGU20 engaged with the online conference, their attitudes in terms of how it compared to a face-to-face event, and whether they thought there were any opportunities that were presented as a result of the event going fully online. This was formalised into the following two research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1: what did people miss from a regular General Assembly?

-

RQ2: to what extent did going online impact the event itself, both in terms of challenges and opportunities?

In answering these questions, we are aware that many people's experiences of the conference relate to the technical limitations of the platforms or specific technical issues experienced during the week. While important, we have not addressed those issues in this analysis for two main reasons. First, technical issues and limitations are an issue faced by all types of conferences and always impact the experience of the attendees. However, for our specific questions, the exact nature of the technical difficulty was not as relevant as the fact that engagement was disrupted. Second, it is also important to note the extremely restricted timescale that the organisers had in moving this conference online. As such, it is highly unlikely that any scientific conference would be held in exactly this way again – particularly when representing this many people.

2.2 Selection of samples to be analysed

The survey was distributed using EGU's preferred survey platform, zohopublic, and the link to the survey was distributed via email to all conveners and authors, as well as EGU members. The link to the survey was also distributed over social media, using the EGU's official Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram accounts, as well as being shared by various other affiliated accounts. The survey was open for responses from 4 May until 1 June 2020.

Once the survey data had been collated and cleaned of incomplete answers, there were 1580 responses. This entire data set was used for the initial implementation of the coding process (see Sect. 2.4). Once the initial codes had been set, and in order to more effectively assess the qualitative responses given to the survey, the total data set of 1580 responses was divided by career stage (early career, mid career, or senior career), which cumulatively represented 1503 responses. Of these career divisions, only one has an associated definition within the EGU's structure (i.e. early career); however, for the purposes of this survey, no definition was applied – all participants were instructed to self-identify their career stage. From these, 50 complete responses that included at least one qualitative answer were selected from each career stage for coding (see Sect. 2.4). This selection included 25 responses from the top of the data set and 25 from the bottom, representing the first and last respondents to the survey from each career stage, respectively.

2.3 Definition of categories to be applied

A conventional approach to qualitative content analysis was adopted in this study, with preconceived categories being avoided and instead being determined by the implementation of the coding process (see Sect. 2.4). While in some instances a directed content analysis might be more appropriate, this is usually used in those instances where an existing theory would benefit from further description (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). As the research questions to be addressed in this study are unique, a directed approach is inappropriate. Similarly, a summative content analysis would fail to fully account for the context of the survey responses alongside their content.

2.4 Outline and implementation of coding process

To begin with, two of the authors (Hazel Gibson and Sam Illingworth) selected the same random sample of 100 survey responses. They then coded responses to the following survey questions:

-

How effective/timely was EGU at communicating the change to the General Assembly?

-

How would you rate the accessibility of Sharing Geoscience Online for you?

-

How would you rate the technical delivery of Sharing Geoscience Online?

-

Was there anything about Sharing Geoscience Online that you would like to see maintained for future General Assemblies?

-

What did you miss most about the General Assembly not being a face-to-face event?

-

What would the ideal format of the EGU General Assembly be, according to you?

-

In what ways has Sharing Geoscience Online supported/could Sharing Geoscience Online support your career?

-

Any further comments?

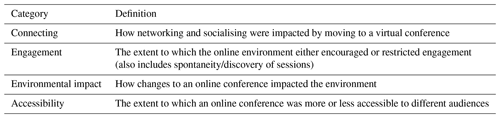

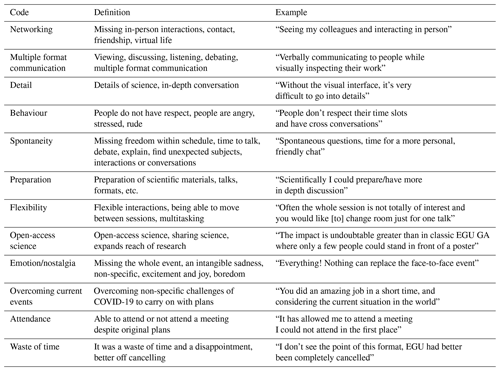

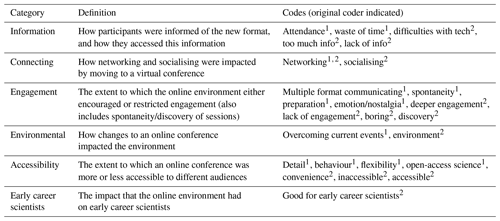

The individual code books that were used by both Hazel Gibson and Sam Illingworth in this initial coding exercise are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Both Hazel Gibson and Sam Illingworth found that data saturation had been reached after coding for 100 survey responses; i.e. there were mounting instances of the same codes but no new ones.

Table 1The code book that was used by Hazel Gibson in the initial coding exercise, including a definition and an example for each code.

Table 2The code book that was used by Sam Illingworth in the initial coding exercise, including a definition and an example for each code.

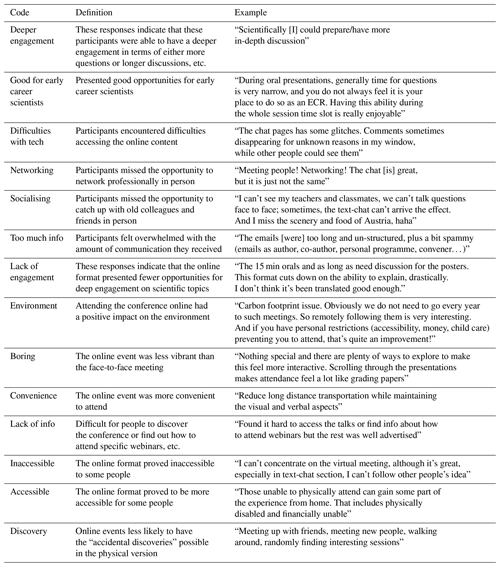

After this initial coding exercise was completed, Hazel Gibson and Sam Illingworth combined their code books and decided on a number of categories that covered all of these codes and which could be used to better represent the narrative that was emerging from the data. These combined categories are shown in Table 3.

Table 3The initial combined categories that were used to classify the initial codes of Hazel Gibson and Sam Illingworth.

1 Hazel Gibson. 2 Sam Illingworth.

After these combined categories had been determined, both Hazel Gibson and Sam Illingworth revisited the original RQs and decided that some of the survey's questions, whose responses had been analysed in the initial coding exercise, were not related to these RQs. The following questions were selected as being most pertinent to answering the RQs (given in parentheses) of this study:

-

How would you rate the accessibility of Sharing Geoscience Online for you? (RQ1)

-

Was there anything about Sharing Geoscience Online that you would like to see maintained for future General Assemblies? (RQ2)

-

What did you miss most about the General Assembly not being a face-to-face event? (RQ2)

-

What would the ideal format of the EGU General Assembly be, according to you? (RQ1, RQ2)

-

In what ways has Sharing Geoscience Online supported/could Sharing Geoscience Online support your career? (RQ2)

-

Any further comments? (RQ1, RQ2)

The other questions (i.e. “How effective/timely was EGU at communicating the change to the General Assembly?” and “How would you rate the technical delivery of Sharing Geoscience Online?”) were deemed to be more related to the technical delivery of an online conference rather than specific learning and attitudes towards the experience of a face-to-face or online event. At this stage in the analysis, the data were cleaned up to remove any responses that did not contain information and also to split the respondents into three broad categories, namely early career scientists, mid-career scientists, and senior career scientists. This split was done according to the specific information that had been provided by the respondents, who, as part of the survey (“What is your career stage/employment status?”), had to self-identify as to which of these categories they belonged.

After cleaning the data, the categories shown in Table 3 were again revisited, and it was decided that the “Information” and “Early career scientists” categories should be dropped from the subsequent analysis: the former because the responses were more concerned with technical changes and difficulties, and the latter because it would be discriminatory to highlight one of the three groups of researchers. As a result, the categories that are shown in Table 4 are those that were used for this final stage of coding and analysis.

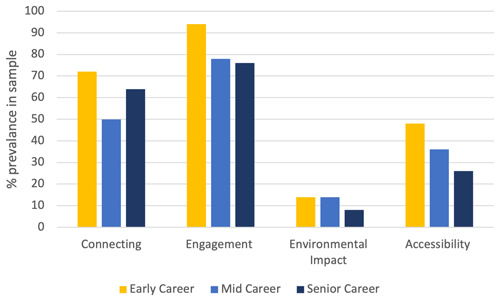

For the final stage of coding, 50 random respondents from each of the three distinct demographic groups (i.e. early career, mid career, and senior career) were selected. Hazel Gibson and Sam Illingworth then individually assigned the categories shown in Table 4 to the responses to the questions given above for these respondents. Figure 1 shows the prevalence of the codes in the sample population to each category theme listed in Table 4 by career stage. Both Hazel Gibson and Sam Illingworth observed that, for each of these 50 sets of responses, the categories that are shown in Table 4 could be assigned with no newly emergent codes or categories during this process, therefore providing confidence that the categories shown in Table 4 represented the dominant narratives to emerge from the data, which will be discussed further in Sect. 3.

2.5 Trustworthiness of coding

At each stage of the qualitative content analysis that was adopted in this study, the individual codes and categories were re-examined in order to confirm that they accurately captured the responses of the survey in relation to the RQ. Both Hazel Gibson and Sam Illingworth carried out this coding independently until there were no further codes or categories found to be emerging from the data, i.e. until descriptive saturation had been reached (Lambert and Lambert, 2012). Similarly, a combination of systematic sampling, constant comparison, and proper audit and documentation (see Sect. 2.2 and 2.4) were used to ensure both the reliability (i.e. the consistency with which this analysis would produce the same results if repeated) and the validity (i.e. the accuracy or correctness of the findings) of this approach (Leung, 2015).

As can be seen from Table 4, four major categories emerged from the methodology that was adopted in analysing the responses to the survey. We now discuss each of these emergent categories, how they relate to RQ1 (“What did people miss from a regular General Assembly?”) and RQ2 (“To what extent did going online impact the event itself, both in terms of challenges and opportunities?”), and how they compare to other research that has been conducted in terms of the transitioning of large academic conferences from physical to virtual spaces.

3.1 Connecting

One of the categories identified from the responses from attendees of EGU20 was “connecting”. This was defined as the interpersonal connections between attendees of the conference, i.e. the human-to-human, individual, or informal interactions. This category is distinct from the connections made around the scientific content, which is discussed in “engagement” (Sect. 3.2).

The responses coded in this category were frequently posted in direct response to the survey question “What did you miss most about the General Assembly not being a face-to-face event?”, and the responses were most often framed as negative or expressing loss. In general, the descriptions of the loss of connection during EGU20 can be summarised as being those opportunities to interact with colleagues and friends “beyond the session”. The loss of connection was most often described in terms of informal interaction, such as the following observation from a senior career scientist:

Personal communications. The possibility to share a lunch or a dinner together with potential future colleagues.

Networking was also a key aspect of the loss of connection, particularly expressed by mid-career scientists and early career scientists searching for career development. The limited scope of a platform, such as the one that was provided during EGU20 for networking, echoes findings of other studies where social media and other digital platforms are often used to build networking potential, which is then followed up for more meaningful discussion in person (Reinhardt et al., 2009; Kimmons and Veletsianos, 2016). The discussion of a loss of connection in networking was also described as a function of learning who is potentially a valuable contact and meeting new people, as this mid-career scientist observed:

The ability to network. Randomly meet people you don't even think you're interested in meeting.

The loss of connection for senior career scientists was especially pronounced in the way they described friendship and treasured colleagues. This was not, however, limited to senior career scientists, and often included an aspect of nostalgia for the conference itself and an enjoyment of the city of Vienna. Many respondents described the loss of contact with friends as being central to their General Assembly experience, as this senior career scientist responded:

90 % of my motivation to go to the EGU General Assembly is to meet with colleagues and friends in person. That's a great loss.

The final aspect of loss with regards to the theme of connection was in the stimulus and inspiration that comes from informal conversation and meetings with people. This was expressed in the form of being able to plan future activities, come up with new ideas, or simply the inspiration that breaking the routine through connection provides, as this early career scientist describes:

Networking, meeting people in person, the atmosphere of the meeting, Vienna, and listening more than reading. My job as a scientist is mostly reading and writing; the physical conference is breaking out of this, which opens many other opportunities to think, cooperate, and pathways to discuss.

These responses show that, though the scientific content is key to any conference, the ability to build and experience meaningful informal connections with friends and colleagues for both personal and professional reasons is very valuable to attendees, which is something that is also present in studies of remote working more generally (Nardi and Whittaker, 2002). This aspect of providing space beyond the session for informal interaction is a useful recommendation for face-to-face conferences as well, but for digital or online conferences, it may prove critical to their success or failure.

3.2 Engagement

Another category to arise from the responses from respondents was that of engagement. Specifically, this was related to the extent to which respondents were or were not able to engage with both the online format and the material that was presented.

In terms of criticisms, several respondents felt as though the format of EGU20 precluded the depth of conversation and scientific rigour that would normally be expected at the conference, as demonstrated by this comment from a senior career scientist:

Maybe I come from an old school, but attending a conference directly offers many possibilities to establish contacts with other scientists, to interact in a deeper and less aseptic way than online event provides.

However, others actually found more opportunity for engagement, both during and after the various sessions. For example, one early career scientist observed the following:

It may be topic related, but this time was the first time that I got exactly the kind of feedback to my presentation I was hoping for. And that came one–two days after the actual presentation via the discussion section and via email.

This dichotomy of opinions was observed across all three respondent groups, and a similarly polarising aspect of engagement was the spontaneity of discovery that is associated with large conferences like the EGU General Assembly. Some respondents noted that one of the things they missed the most was the opportunity to walk in accidentally or purposefully on sessions outside of their field of expertise, thereby helping to cross-pollinate scientific discourse and helping them to develop their own interdisciplinary approaches. This attitude is evident in the following comment from a mid-career scientist when noting what it was that they missed most about EGU20 not being a face-to-face event:

Wandering around and going to attend a random session outside of my field of expertise.

However, others felt the exact opposite, i.e. that the online format actually made it more possible to engage in research outside of their specific field of expertise, as evidenced by this comment from a senior career scientist:

I could take part in sessions at the fringe of my expertise since the short summaries given by presenters helped me to understand their core message.

The short summaries that this respondent refers to, in combination with the pre-uploaded longer presentations, is one facet of engagement that seems to have been received with almost unanimous positivity. As discussed in Sect. 1.2, for EGU20's scientific sessions, authors were encouraged to upload and share their presentation materials and opt in to commenting from 1 April 2020 onwards, and then prepare a one or two sentence summary of these presentation materials for the live text chat. This meant that participants had up to a month to view other researchers' work in detail and prepare any questions for the allocated session and associated chat during the week of EGU20 itself (4 to 8 May 2020). The opportunity to view this work in advance was a frequent feature of responses to the question “Was there anything about Sharing Geoscience Online that you would like to see maintained for future General Assemblies?”. For example, one early career scientist noted the following:

This made it much easier to think about the contents without the stress of everything around you in the conference centre.

The following comment from a mid-career scientist echoed the sentiment of many respondents that this is a feature that should be utilised in future General Assemblies:

Uploading `displays' online, for anyone to see and comment. Even for a physical meeting it would be useful for the general public or the colleagues who couldn't make it (either to the conference or to the session).

However, the positive response to this pre-release of information must be caveated by the concerns that many respondents raised around potential issues with intellectual property and the dangers of permanently hosting preliminary results online, as evidenced by the following comment from a mid-career scientist:

I'm concerned about the copyright issues when uploading presentations.

One senior career scientist went further, noting the following:

Conferences are often about discussing preliminary results; when I submit an abstract I DO NOT subscribe to permanently DOI-ing preliminary results.

The outcomes of this category are very mixed, with some respondents finding EGU20 to be less engaging than a normal General Assembly, while others noted that it actually presented more opportunities for deep engagement. It would appear that attitudes towards engagement depended very much on the respondent's personal attitudes at the time towards online vs. face-to-face conferences. A more general comment would also be that the experience of EGU20 does not appear to have swayed many respondents from what are clearly deeply entrenched viewpoints. One thing that is made clear from the respondents, however, is that they deeply valued the opportunity to view scientific research in advance of the conference, although this option needs careful consideration with regards to intellectual property and the sharing of preliminary results.

3.3 Environmental impact

One of the clear opportunities that arose from the EGU20 format was the positive impact that this was perceived to have on the environment, i.e. through the reduced carbon emissions associated with attendees travelling to Vienna to participate in a General Assembly. This manifested itself across all three distinct demographic groups (early career scientist, mid-career scientist, and senior career scientist).

The EGU has previously taken several steps to mitigate and offset the impact that travel to the General Assembly has on the environment, as discussed in Sect. 1. Of course, the environmental impact of hosting a large conference like the EGU General Assembly extends beyond that of travel and also includes the printing of materials, the consumption of power at the venue, and the sourcing of catering. The conference venue, the Austria Centre Vienna (ACV), has a number of green measures in place, including having energy-saving LED lights throughout the centre, using a solar array to heat the water used in the kitchens and toilets, and working with an in-house catering company compliant with green standards. Other measures that have been implemented to reduce the environmental impact of the General Assembly include no longer offering single-use water bottles during breaks, installing water fountains for refilling multi-use bottles, phasing out printed copies of the programme book, and making sure that the lanyards are created out of 100 % recyclable materials.

If the 2020 event had taken place in Vienna, all travel of participants would have been carbon offset, and, additionally, there would have been promotion of bicycle transport in Vienna, both within the ACV and through official communication channels. However, from the results of this survey, these steps do not go far enough to alleviate the concern that many of the respondents have with regards to the environmental impact of the General Assembly. Furthermore, as noted by Hischier and Hilty (2002), the environmental impact of a large international conference such as the EGU General Assembly is dominated by the travel activities of the participants. Here long-range flights are the dominant element, as exemplified for the 2019 Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union, where 75 % of the emissions were due to intercontinental flights over distances larger than 8000 km made by 36 % of the attendees (Klöwer et al., 2020). Klöwer et al. (2020) point out that, for the 2019 EGU General Assembly in Vienna, virtual participation for 26 % of the highest-emitting participants would reduce the carbon footprint by 80 % (https://github.com/milankl/CarbonFootprintEGU, last access: 11 December 2020). As such, despite any green measures that EGU may take in Vienna, minimising air travel is the only way to ensure a significant reduction in the environmental impact.

The hard decisions that many researchers face with regards to the environmental impact of attending the General Assembly are evident from the following two comments (both from early career scientists):

As geologists we really need to think about being more climate friendly in our jobs!

In order to cut the carbon footprint of science, we need to go online more and have less [sic] actual meetings (although I prefer those).

Despite these quotes coming from early career scientists, this environmental conflict of interest was felt keenly across the three groups. For example, one senior career scientist observed the following:

because the environmental foot print [sic] of normal EGU seems unreasonable nowadays, we have to think differently, and this crisis pushes a bit to [sic] far but shows us alternatives.

As a result of this conflict of interest, many of the respondents (across all three groups) suggested varying hybrid models of face-to-face and online options for future EGU General Assemblies, citing environmental concerns as their primary reasons for moving away from a strictly “business-as-usual” model.

The internal conflict of several of the respondents is appropriately reflected by this comment from a senior career scientist:

The online format is a great opportunity to reduce the environmental impact of the GA [General Assembly] and allows people to attend who cannot travel. But face-to-face meetings are important too. I would favour alternating between online and physical meetings. [sic] in the future. Both have advantages.

In total, 16 273 scientists participated in the EGU General Assembly 2019 in Vienna, Austria. Klöwer et al. (2020; https://github.com/milankl/CarbonFootprintEGU, last access: 11 December 2020) estimated that these scientists travelled 94 million kilometres in total to Vienna and back, which emitted 22 300 t of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e), an average of approximately 1.4 tCO2e per scientist. To put this into context, this is the total weekly carbon footprint of approximately 27 000 average American households, and based on other studies (see, e.g., Green, 2008; Jäckle, 2019; Bousema et al., 2020), this might be considered to be a conservative estimate.

As noted by Bousema et al. (2020), although in-person meetings have many benefits, the ecological impact of conference travel is considerable and demands action. With more than 16 000 attendees, the EGU General Assembly has a substantial environmental impact, and while the EGU has taken several steps to reduce their impact, it is clear that this is an issue that is not being adequately addressed. Even allowing for the environmental impact of hosting a large online event (Versteijlen et al., 2017), the reduction in carbon emissions from thousands of people not travelling to Vienna every year is substantial. Whatever format is taken by future EGU General Assemblies, the results of this survey indicate that something needs to be done to better mitigate the environmental damage that a face-to-face conference presents in its current guise. Perhaps this is the opportunity we have been waiting for to lead by example and transition to a General Assembly that not only presents research on how to mitigate climate change but also takes actionable steps in doing so. As observed by one early career scientist:

If it was only online, we'd have to adapt to a new way of working, which would ultimately accelerate our transition to a green future.

3.4 Accessibility

The fourth category identified in coding is one that is often cited in connection with the benefits of online conferences: “accessibility”. In this case, accessibility was related to any discussion of increasing the ability of people to participate in the General Assembly, regardless of the reason for their inability to participate at other times. Though this has particular relevance to under-represented groups in academia, such as those who have a disability, caring responsibilities, financial constraints, or are excluded due to systemic oppression. This category also included people who may attend in a normal year but who could not for a specific reason in 2020.

The first thing to note here is that responses coded as being about accessibility were overwhelmingly positive. There was a general appreciation of the ability of an online General Assembly to widen participation – particularly for those who would not normally be able to attend. as these early career scientists stated:

Those unable to physically attend can gain some part of the experience from home. That includes physically disabled and financially unable.

I think the online format allowed people who could not come to the meeting for cost or travel restrictions to attend, thus broadening the scientific content.

Financial constraints were often stated as a limiting factor, but connected to this was the burden of travel and all that it entailed – particularly the challenge of obtaining documentation for residents of certain countries – but many also recognised the value of being able to invite nontraditional conference attendees that would also normally experience a financial barrier, thus encouraging open science, as this mid-career scientist stated:

Open access and open chat to everyone who can log in with their email; also, stakeholders could attend as a guest!

In addition to improving the accessibility of the scientific information, it was also noted that there was more support for those less inclined to engage in traditional forms of conference questioning (which can be quite combative at times), such as people who are perhaps at an earlier career stage or of a more introverted personality, as observed by this mid-career scientist:

Accessibility for those with caring responsibilities, lack of financial resources, etc. And the fact that many are more comfortable asking questions in an online format > good for introverts and ECRs.

However, many stated that, despite the improved accessibility, the online conference was something that should, in future, be relegated to being supplemental to a traditional in-person conference. Some even described the accessibility of an online conference as a trade-off, as this senior career scientist said:

The expanded attendance is good, but there is definitely something lost but also something gained (accessibility).

The benefits of an online conference for accessibility cannot be ignored, and it is important to note how many respondents also identified ways in which accessibility in this regard truly went beyond some narrower definitions to really widening participation. Although the majority of respondents discussed accessibility in positive terms, we must also recognise, as with other discussions of accessibility, the question of who is included in this survey and who is excluded and how online engagement continues to include or exclude certain people, often compounding exclusion in non-digital spaces (Khalid and Pedersen, 2016). Even within the initial design stages of the emergency build of this online conference, the organisers were conscious of several areas in which they did not have the capacity to make EGU20 fully accessible – and because of that it is very likely that there are important voices missing from these data.

The original purpose of this study was to address the following two research questions:

-

RQ1: what did people miss from a regular General Assembly?

-

RQ2: to what extent did going online impact the event itself, both in terms of challenges and opportunities?

As can be seen from Sect. 3, it is evident that there are several aspects of a face-to-face EGU General Assembly that were missed by respondents, not least the opportunity to connect and interact with colleagues in informal environments. It is also clear from these emergent narratives that there are many aspects of going online that present opportunities that should not be forgotten for future General Assemblies. The future of the EGU General Assembly is something that requires careful consideration, and indeed many of the choices are driven by change outside the control of the EGU Executive Board and Programme Committee; the 2021 General Assembly was also run as a fully online event because of the restrictions that continue to be imposed by COVID-19. However, there are still many variables that are within their control, and it is clear from the responses to the survey that many participants feel very strongly that a fully online or hybrid General Assembly is not only an option but a necessity in order to both make the conference more accessible and also to address the significant environmental impact of hosting a face-to-face intentional conference. In moving towards any digital provision for future General Assemblies, we would like to offer the following recommendations, which have emerged from the results of this study:

-

The online provision should not just be an afterthought. An online digital conference cannot simply be a replication of a face-to-face version. Similarly, if a hybrid option is pursued, then there needs to be equal value attached to both the face-to-face and digital aspects. Care should be taken to enable direct interactions between those on-site and remote participants.

-

There needs to be an accessible and innovative space to enable informal connections. One of the biggest issues that needs to be addressed in an online environment is in creating spaces where researchers can meet up with old colleagues, encounter new ones, and informally engage with one another. The café culture of Vienna cannot be replicated in an online format, but then nor is it replicated in the actual General Assembly itself. Digital interactions that take place on platforms that already exist for such encounters need to be considered.

-

Accessibility needs to be reconsidered. Online conferences make science much more accessible to many different groups and help to truly diversify science. However, it also presents several additional access needs that need to be considered. These include, but are not limited to digital literacy, accessibility for visual or hearing impaired participants, access to fast and reliable broadband, and limitations imposed by time zones.

-

The sharing of preliminary results needs to be carefully thought through. One of the highlights from EGU20 was the capacity for people to see (and comment on) scientific research before it was presented. Enabling this feature for a future General Assembly would be well received, but careful consideration needs to be given as to how to ensure that all researchers feel confident that their research is protected as we increasingly move into an era of open science, especially for those who work with confidential data.

These recommendations are directed specifically at future designs for the EGU General Assembly, but the authors would be interested to see how results from other large-scale science conferences that went through this experience compare, with an aim of finding out if these recommendations could apply more broadly to the sector. The validity and reliability of this study is discussed in Sect. 2.5, but it should be noted that, as with any qualitative analysis, there is a degree of interpretation in the analysis of the responses to the survey. However, we are confident that the emergent narratives are representative of the general zeitgeist of EGU participants.

The format of EGU20 was radically changed because of the impacts of COVID-19, and while there are clearly issues that need to be addressed for any future online version of the EGU General Assembly (either fully online or in some hybrid form), it has perhaps forced a change that might not have otherwise occurred. The organisers and participants of subsequent General Assemblies need to think very carefully about whether the perceived positive impacts of a traditional face-to-face conference outweigh the very real concerns about inclusion and environmental impact. As one of the respondents to the survey noted:

The traditional conference is getting more difficult to justify with climate change and the requirement that everyone jet around the world to discuss Earth science, especially science related to climate change.

If the community does not listen to these requests and consider them very seriously, then we are at risk of being nothing more than a data point on the business-as-usual climate simulations that many of us have dedicated our professional lives to mitigating against.

Thank you for participating in the feedback survey for EGU Sharing Geoscience Online 2020! This has been an unprecedented experiment, where we organised the largest virtual gathering of geoscientists ever in only 6 weeks since the cancellation of the physical General Assembly. We are very curious about your experience at Sharing Geoscience Online: what has worked well, what could be better, what did you miss, and what should EGU consider to keep for future meetings.

We would like to ask you to take 5–10 minutes to complete this questionnaire, as your input is very helpful for shaping future EGU General Assemblies and possible virtual extensions.

Susanne Buiter (RWTH Aachen University)

Chair of the EGU General Assembly 2020 Programme Committee

-

Q1. What EGU programme groups do you associate most closely with?

- -

Atmospheric Sciences

- -

Biogeosciences

- -

Climate: Past, Present & Future

- -

Cryospheric Sciences

- -

Education and Outreach Sessions

- -

Earth Magnetism & Rock Physics

- -

Energy, Resources & the Environment

- -

Earth & Space Science Informatics

- -

Geodesy

- -

Geodynamics

- -

Geosciences Instrumentation & Data Systems

- -

Geomorphology

- -

Geochemistry, Mineralogy, Petrology & Volcanology

- -

Hydrological Sciences

- -

Interdisciplinary & Transdisciplinary Sessions

- -

Natural Hazards

- -

Nonlinear Processes in Geosciences

- -

Ocean Sciences

- -

Planetary & Solar System Sciences

- -

Short Courses

- -

Seismology

- -

Special Scientific Events

- -

Stratigraphy, Sedimentology & Palaeontology

- -

Soil System Sciences

- -

Solar-Terrestrial Sciences

- -

Tectonics & Structural Geology

- -

None

- -

-

Q2. What is your present country of employment/study?

-

Q3. What is your gender?

- -

Female

- -

Male

- -

Non-Binary

- -

Prefer not to say

- -

Prefer to self describe

- -

-

Q4. Did you feel restricted to participate in the conference due to some physical limitations?

-

Q5. Does any of the following apply?

- -

It is difficult for me to attend physical meetings, but I could attend Sharing Geoscience Online

- -

It is difficult for me to attend physical meetings, and I also experienced difficulties attending Sharing Geoscience Online

- -

I can attend physical meetings but experienced difficulties attending Sharing Geoscience Online

- -

I can attend physical meetings and Sharing Geoscience Online

- -

Other/Comments

- -

-

Q6. Why did you give this answer?

-

Q7. What is your career stage/employment status?

- -

Early career scientist

- -

Mid-career scientist

- -

Senior scientist

- -

Retired

- -

Self-employed

- -

Not currently employed

- -

Other

- -

-

Q8. What is your role at EGU Sharing Geoscience Online 2020? (Tick all that apply)

- -

Abstract author or co-author

- -

Session convener or co-convener

- -

Session chair

- -

EGU division scientific officer

- -

EGU Programme Committee member

- -

EGU council member

- -

Scientific participant

- -

Press/media

- -

Other (Please State)

- -

-

Q9. Have you attended a virtual conference before?

-

Q10. Which one?

-

Q11. How effective/timely was EGU at communicating the change to the General Assembly?

- -

Very Good

- -

Good

- -

Average

- -

Poor

- -

Very Poor

- -

-

Q12. Why did you give this score?

-

Q13. What were your main sources of information about the changes to the General Assembly? (Tick all that apply)

- -

EGU website (https://www.egu.eu/)

- -

General Assembly website (https://www.egu2020.eu/)

- -

Social Media

- -

Blogs

- -

Newsletter

- -

E-mails by EGU/Copernicus

- -

Other (Please specify)

- -

-

Q14. Which activities of Sharing Geoscience Online did you participate in?

- -

Scientific Sessions

- -

Union Symposia

- -

Great Debates

- -

Short Courses

- -

Townhall Meetings

- -

Photo Competition

- -

#shareEGUart

- -

Division Meetings

- -

Networking Events

-

Closing Party

- -

-

Q15. How many different chat sessions of Sharing Geoscience Online did you participate in?

-

Q16. How would you rate the accessibility of Sharing Geoscience Online for you?

- -

Very Good

- -

Good

- -

Average

- -

Poor

- -

Very Poor

- -

-

Q17. Why did you give this answer?

-

Q18. How would you rate the technical delivery of Sharing Geoscience Online?

- -

Very Good

- -

Good

- -

Average

- -

Poor

- -

Very Poor

- -

-

Q19. Why did you give this answer?

-

Q20. Was there anything about Sharing Geoscience Online that you would like to see maintained for future General Assemblies?

-

Q21. What did you miss most about the General Assembly not being a face-to-face event?

-

Q22. What would the ideal format of the EGU General Assembly be according to you?

- -

Face-to-face event only

- -

Mixed face-to-face and online event

- -

Online event only

- -

-

Q23. Why did you give this answer?

-

Q24. In what ways has Sharing Geoscience Online supported/could Sharing Geoscience Online support your career?

-

Q25. Any further comments?

Given that the data contain responses that could lead to the identification of the respondents (even with their name and institute redacted), we have chosen not to make the survey responses available, but a redacted version can be provided upon request.

HG and SI wrote and conducted the survey, sampled and coded the results, and produced the first analysis. SB provided details of the design of the emergency conference, provided context and feedback from the Executive Board, and reviewed the analysis. All authors co-wrote the paper.

Hazel Gibson is an associate editor of Geoscience Communication, Sam Illingworth is the chief executive editor of Geoscience Communication, and Susanne Buiter was the chair of the Programme Committee for EGU2020: Sharing Geoscience Online and is an executive editor of Solid Earth.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors thank the hundreds of volunteers around the globe who have worked so hard to shape EGU2020: Sharing Geoscience Online, an exciting experiment in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and a great success throughout the entire week, and especially the Programme Committee (Raffaele Albano, Jonathan Bamber, Anouk Beniest, Johannes Böhm, Marc De Batist, Ira Didenkulova, Michael Dietze, Olaf Eisen, Fabio Florindo, Helen M. Glaves, Karen Heywood, Marian Holness, Patric Jacobs, Philippe Jousset, Chris King, Olga Malandraki, Mioara Mandea, Sonja Martens, Alberto Montanari, Athanasios Nenes, Lena Noack, Lara Pajewski, Giuliana Panieri, Dan Parsons, Maria-Helena Ramos, Didier Roche, Claudio Rosenberg, Håkan Svedhem, Paul Tackley, Peter van der Beek, Stéphane Vannitsem, Stephanie C. Werner, and Claudio Zaccone) for their tireless efforts. The authors would also like to extend their thanks to Copernicus Meetings (Mario Ebel, Katja Gänger, Katharina Huckemeyer, Katrin Krüger, Martin Rasmussen, Stefan Schwardt, and Hennadii Shvedko) and to the other EGU Office staff (Terri Cook, Chloe Hill, and Philippe Courtial) for their dedication to making Sharing Geoscience Online a success.

This paper was edited by Stephanie Zihms and reviewed by Jen Roberts and Anthea Lacchia.

Bousema, T., Selvaraj, P., Djimde, A. A., Yakar, D., Hagedorn, B., Pratt, A., Barret, D., Whitfield, K., and Cohen, J. M.: Reducing the Carbon Footprint of Academic Conferences: The Example of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 103, 1758–1761, https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-1013, 2020.

Desiere, S.: The carbon footprint of academic conferences: Evidence from the 14th EAAE Congress in Slovenia, EuroChoices, 15, 56–61, https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-692X.12106, 2016.

De Picker, M.: Rethinking inclusion and disability activism at academic conferences: strategies proposed by a PhD student with a physical disability, Disabil. Soc., 35, 163–167, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1619234, 2020.

Erlingsson, C. and Brysiewicz, P.: A hands-on guide to doing content analysis, African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 7, 93–99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001, 2017.

Foramitti, J., Drews, S., Klein, F., and Konc, T.: The virtues of virtual conferences, J. Clean. Prod., 294, 126287, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126287, 2021.

Green, M.: Are international medical conferences an outdated luxury the planet can't afford? Yes, BMJ, 336, 1466, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a358, 2008.

Hamant, O., Saunders, T., and Viasnoff, V.: Seven steps to make travel to scientific conferences more sustainable, Nature, 573, 451–452, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-02747-6, 2019.

Hischier, R. and Hilty, L.: Environmental impacts of an international conference, Environ. Impact Asses., 22, 543–557, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-9255(02)00027-6, 2002.

Hsieh, H. F. and Shannon, S. E.: Three approaches to qualitative content analysis, Qual. Health Res., 15, 1277–1288, https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687, 2005.

Illingworth, S.: “This bookmark gauges the depths of the human”: how poetry can help to personalise climate change, Geosci. Commun., 3, 35–47, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-3-35-2020, 2020.

Jäckle, S.: WE have to change! The carbon footprint of ECPR general conferences and ways to reduce it, Eur. Polit. Sci., 18, 630–650, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-019-00220-6, 2019.

Khalid, M. S. and Pedersen, M. J. L.: Digital exclusion in higher education contexts: A systematic literature review, Procd. Soc. Behv., 228, 614–621, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.094, 2016.

Kimmons, R. and Veletsianos, G.: Education scholars' evolving uses of twitter as a conference backchannel and social commentary platform, Brit. J. Educ. Technol., 47, 445–464, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12428, 2016.

Klöwer, M., Hopkins, D., Allen, M., and Higham, J.: An analysis of ways to decarbonize conference travel after COVID-19, Nature, 583, 356–359, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02057-2, 2020.

Lambert, V. A. and Lambert, C. E.: Qualitative descriptive research: An acceptable design, Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research, 16, 255–256, 2012.

Leung, L.: Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research, Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 4, 324–327, https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.161306, 2015.

Nardi, B. A. and Whittaker, S. The place of face-to-face communication in distributed work, Distributed work, 83, 112, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2464.003.0008, 2002

Reinhardt, W., Ebner, M., Beham, G., and Costa, C.: How people are using Twitter during conferences, in: Creativity and Innovation Competencies on the Web, Proceedings of the 5th EduMedia, Salzburg, Austria, May 2009, 145–156, 2009.

Versteijlen, M., Salgado, F. P., Janssen-Groesbeek, M., and Counotte-Potman, A. D.: Structural reduction of carbon emissions through online education in Dutch Higher Education, in: Symposium on Learning and Innovation in Resilient Systems, 23–24 March 2017, Heerlen, Netherlands, 2017.