the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

GC Insights: The Anthro-Pokécene – environmental impacts echoed in the Pokémon world

Lewis J. Alcott

Taylor Maavara

Public perception of anthropogenic environmental impacts, including climate change, is primarily driven by exposure to different forms of media. Here, we show how Pokémon, the largest multimedia franchise worldwide, mirrors public discourse in the video games' narratives with regard to human impacts on environmental change. Pokémon demonstrates a trajectory towards greater acknowledgement of climate change and anthropogenic impacts in each released game and presents a hopeful vision for how society can adapt.

- Article

(816 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2903 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The public perception and societal importance of anthropogenic impacts on the environment, including climate change, has evolved over recent decades. This perception is shaped and reflected by political discourse and news media, as well as creative and narrative media, including movies, television, literature, and video games illustrating climate and environmental change (Bulfin, 2017; McCormack et al., 2021). Video games take over 3 billion players to virtual worlds where they can assimilate information as they see and interact with virtual environments (Bankhurst, 2020) and have been recognized for their potential to teach and expose players to learning concepts for decades (Adams, 1998; De Freitas, 2018; Squire et al., 2008).

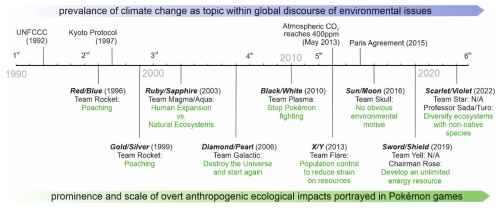

Figure 1Original release timeline of main-series Pokémon games and the evolution of global discourse surrounding climate change, benchmarked using climate action or impact milestones since 1990. The qualitatively coded themes of the antagonists' motives are highlighted in green. Numbered Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports are noted above the timeline, first through sixth.

Research into Earth and environmental science's representation in video games is still a growing field (Clements et al., 2022; Hut et al., 2019; McGowan and Alcott, 2022; McGowan and Scarlett, 2021), with many video games inspired by real-world settings, events, or locations, making them ideal for teaching environmental features, processes, and interactions. Pokémon is the largest media franchise worldwide with a total revenue of nearly USD 100 billion (Bulchoz, 2021), with 122 total games across nine generations, merchandise, trading cards, numerous theatrical film releases, and a TV series spanning decades (The Pokémon Company, 2022). Through gameplay, players can explore interactions between anthropogenic and natural settings, showcasing and exposing human impacts on local and global ecosystems to audiences of all ages. As is well documented, climate change is a global challenge, and with Pokémon media available across 192 countries (The Pokémon Company, 2022), it is uniquely poised to be a valuable resource as a climate change knowledge distributor. Therefore, we ask the following questions: how have the Pokémon video games' representations of environmental change and sustainable practices evolved over the past 3 decades, and how have they mirrored public discourse and priorities?

We played the main series of Pokémon games released from 1996 to 2023 and thematically analysed driving narratives, imagery, and mentions of anthropogenic impacts in the games, including the games' Pokédex (Bulbapedia, 2024), to evaluate evolving environmental themes. To further define the motives identified from the games, quotes were collated from each generation of games by interrogating game scripts, with themes and representative quotes summarized. Finally, positive representations of sustainable practices are also identified and summarized in the Supplement.

The modern geologic era is often referred to as the Anthropocene due to widespread human impacts across geologies and ecosystems caused by human impacts, including climate change (Waters, 2016). The extent to which the Anthropocene is represented in the Pokémon main series games reflects prominent topics within real-world public discourse. We thus refer to the era of anthropogenic change portrayed in the Pokémon world as the Anthro-Pokécene.

The first four generations (Red, Blue, and Yellow; Gold, Silver, and Crystal; Ruby and Sapphire; and Diamond, Pearl, and Platinum), released between 1996 and 2006, represent some elements of anthropogenic change, but these are largely limited to minor game script comments, Pokédex entries, or weak inferences that players could draw from game details, like the villainous “nefarious team” plot line (e.g. Team Rocket's efforts to poach Pokémon). These games coincided with a time in history when climate change was not the most central environmental topic in virtually all discourse that it is today (Holland, 2019; Media and Climate Change Observatory, 2023). In the 1990s, anthropogenic impacts to ecological systems that were often highlighted included poaching, overhunting, overfishing, and habitat destruction via deforestation and industrial pollution, which were in turn the issues highlighted in these early games. All the game development for Red, Blue, and Yellow, and likely a large proportion for Gold and Silver, was completed before the Kyoto Protocol was signed in 1997, which represented a major step in terms of bringing climate change into public awareness (Fig. 1).

As global climate discourse proliferated in the late 2000s and 2010s, the franchise grew and transitioned to better represent the nuance and complexity of environmental change. Narratives became morally ambiguous as game themes dealt with complex environmental decision-making in an increasingly politically polarized world. A clear example of this moral ambiguity is found in the sixth-generation games (X and Y, 2013): the antagonist wishes to return the planet to a “beautiful” and “unspoiled” state, and while arguably well intentioned, the plan included eliminating most of the world's population to lessen pressure on the natural world. This storyline mirrors fraught real-world arguments that overpopulation is a root cause of climate change. Without being sanctimonious, this concept being presented by the game's antagonist inherently causes players to question the ethics of calls to reduce the human population as a viable solution to climate change through exposure and discussion of the subject, which they may not otherwise be witness to. The conclusion of this story notes that to create a better world, people must cooperate globally, which is often quoted as a necessary approach to lessen climate impacts, with the COP26 meeting being subtitled “Together for our planet” (The United Nations, 2021), and cooperation being explicitly cited as a means of climate resilient development in recent IPCC reports (IPCC, 2023).

More recent games acknowledge real-world environmental issues more directly, especially in games set in Alola (Sun, Moon, UltraSun, and UltraMoon, 2016) and Galar (Sword and Shield, 2019), which depict contrasting environmental situations in ways accessible to a general audience. These games were released following the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015 (Fig. 1), a time when the global environmental discourse had become vocally aware of the urgent need to address the climate emergency. Alola is a Hawaiian-island-inspired environmental utopia with a rich ecological diversity due to endemic island species. Galar is a UK-inspired industrialized region in which the implications of pollution are evident. The most overt representations of anthropogenic influence in the franchise arose in Galar. For example, the coral Pokémon Corsola, previously depicted as a healthy pink coral, appears in Galar as a white bleached coral and changes from rock and water type to ghost type as the “living” version was wiped out by ocean acidification driven by climate change.

While the Pokémon franchise excels in its presentation of complex environmental situations to a varied audience, the games notably present an overall hopeful representation of society's ability to respond to environmental change (examples listed in the Supplement). The games have transitioned from including polluting power plants (Red and Blue, 1996) to renewable energy solutions such as wind farms (Diamond and Pearl, 2006), solar power (X and Y, 2013), and geothermal energy production (Sun and Moon, 2016). This transition is not restricted to the progression of generations of Pokémon games; the remakes of Gold and Silver (1998), named HeartGold and SoulSilver (2010), saw the introduction of wind turbines across the region, ultimately leading to their widespread depiction in the most recent games, Scarlet and Violet. Several games also include bicycle paths and wildlife protection zones to demonstrate how the player can respect the environment. Without ever needing to think critically about the game plot lines, by playing the games and remakes released since ∼ 2010, players are moving through and interacting with worlds that represent examples of sustainable, renewable-based living.

For many, Pokémon is a gateway to appreciating the natural world and understanding the scope and complexity of responding to environmental change (Rangel et al., 2022). Whilst we have noted examples of negative human–ecosystem interactions, the Pokémon games expose players of all ages and demographics to ecological and environmental concepts, likely many for the first time. Pokémon has progressed to present a more hopeful balance between humans and the environment over the past few decades. By doing so, they represent how popular media has come to mirror public discourse and society in aiming for a better planet, albeit whilst presenting moral dilemmas through antagonists' actions.

All data were collected through http://bulbapedia.bulbagarden.net (Bulbapedia, 2023) and the game scripts as described in the Methods section. Data can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26583709.v3 (Alcott, 2024). Additional background information about the game can be found at https://corporate.pokemon.co.jp/en/ (last access: 6 December 2022, The Pokémon Company, 2022). We do not have permission from the developers to share free access to the game. However, it is publicly accessible to purchase.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-8-47-2025-supplement.

Both authors contributed to all aspects of the manuscript.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Geoscience Communication. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

The work presented is original and reflects the authors' views. Ethics approval and informed consent were not sought; this study does not deal with sensitive data or human participants.

The authors explicitly state that they have no commercial ties to The Pokémon Company, Nintendo corporation, and/or its affiliates. This paper describes work from a copyrighted video game or otherwise copyrighted material. The copyright for it is most likely owned by either The Pokémon Company, Nintendo and/or its affiliates, or the person or organization that developed the concept.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

Taylor Maavara was supported by an Independent Research Fellowship from the United Kingdom's Natural Environment Research Council (NERC; grant no. NE/V014277/1).

This paper was edited by Caitlyn Hall and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Alcott, L.: Quotes.xlsx, figshare [data set], https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26583709.v3, 2024.

Adams, P. C.: Teaching and learning with SimCity 2000, J. Geograph., 97, 47–55, https://doi.org/10.1080/00221349808978827, 1998.

Bankhurst, A.: Three billion people worldwide now play video games, new report shows, https://www.ign.com/articles/three-billion-people-worldwide-now-play-video-games-new-report-shows (last access: 6 December 2024), 2020.

Bulbapedia: Bulbagarden – The Original Pokémon Community, http://bulbapedia.bulbagarden.net (last access: 1 December 2024), 2023.

Bulbapedia: Core series, Retrieved 26th July from https://bulbapedia.bulbagarden.net/wiki/Core_series (last access: 26 July 2024, 2024.

Bulchoz, K.: The Pokémon Franchise Caught 'Em All, https://www.statista.com/chart/24277/media-franchises-with-most-sales/ (last access: 25 November 2024), 2021.

Bulfin, A.: Popular culture and the “new human condition”: Catastrophe narratives and climate change, Global Planet. Change, 156, 140–146, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2017.03.002, 2017.

Clements, T., Atterby, J., Cleary, T., Dearden, R. P., and Rossi, V.: The perception of palaeontology in commercial off-the-shelf video games and an assessment of their potential as educational tools, Geosci. Commun., 5, 289–306, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-5-289-2022, 2022.

De Freitas, S.: Are games effective learning tools? A review of educational games, Journal of Educational Technology and Society, 21, 74–84, 2018.

Holland, P.: What were the key environmental issues during the 1990s?, https://www.enotes.com/topics/social-political-change-modern-america/questions/what-were-some-environmental-issues-during-1990s-343179 (last access: 9 June 2024), 2019.

Hut, R., Albers, C., Illingworth, S., and Skinner, C.: Taking a Breath of the Wild: are geoscientists more effective than non-geoscientists in determining whether video game world landscapes are realistic?, Geosci. Commun., 2, 117–124, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-2-117-2019, 2019.

IPCC: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Lee, H. and Romero, J., IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 35–115, https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647, 2023.

McCormack, C. M., Martin, J. K., and Williams, K. J. H.: The full story: Understanding how films affect environmental change through the lens of narrative persuasion, People and Nature, 3, 1193–1204, https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10259, 2021.

McGowan, E. G. and Alcott, L. J.: The potential for using video games to teach geoscience: learning about the geology and geomorphology of Hokkaido (Japan) from playing Pokémon Legends: Arceus, Geosci. Commun., 5, 325–337, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-5-325-2022, 2022.

McGowan, E. G. and Scarlett, J. P.: Volcanoes in video games: the portrayal of volcanoes in commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) video games and their learning potential, Geosci. Commun., 4, 11–31, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-4-11-2021, 2021.

Media and Climate Change Observatory: 2004–2025, World Newspaper Coverage of Climate Change or Global Warming, https://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/icecaps/research/media_coverage/world/index.html (last access: 4 December 2024), 2023.

Rangel, D. O., Lima, J. S., Da Silva, E. F. N., Ferreira, K. A. and Costa, L. L.: Pokémon as a playful and didactic tool for teaching about ecological interactions, J. Biol. Educ., 58, 119–129, https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2022.2026803, 2022.

Squire, K. D., DeVane, B., and Durga, S.: Designing centers of expertise for academic learning through video games, Theor. Pract., 47, 240–251, https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802153973, 2008.

The Pokémon Company: History | The Pokémon Company, https://corporate.pokemon.co.jp/en/aboutus/history/ (last access: 23 November 2024), 2022.

The United Nations: COP26: Together for our planet, https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cop26 (last access: 1 December 2024), 2021.

Waters, C. N.: The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene, Science, 351, 6269, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad2622, 2016.